Hiking buddy Rich and I have already hiked the entirety of the Ozark Trail, doing so in 5–15 mile segments from 1996 through 2015. Since then, we have been redoing some other the segments in the reverse direction from the first time, the eventual goal thus being to hike the entirety of the Ozark Trail in both directions. Today was a small contribution to that goal, in which we did the short section between the fire tower at Taum Sauk State Park (containing Missouri’s highest point at 1,772’ asl) and Russell Mountain.

The forecast was not promising, with steady rain predicted and temperatures remaining in the 30s. Still, Rich and I are not prone to cancelling a hike due to less than ideal conditions, so we arrived at Taum Sauk Mountain mid-morning despite the periodic rain and decided to give it a go. It was a good decision—our rain jackets and warm underlayers kept us confortable, and we were rewarded for our tenacity with an serenely beautiful look at the craggy, water-soaked landscape.

It was slow going as we both forgot our hiking sticks, forcing us to more deliberately choose our footing on the rugged, rocky, boulder-strewn trail. Normally on a winter hike, it is the buds, bark, and remnant leaves that I pay attention to as I strive to identify the component trees comprising the forest around me. Today, however, with intermittent light rain, heavy moisture-laden air, and our eyes mostly looking downward to choose our next footstep, it was the ferns, mosses, and lichens—bright green and water-swollen—that captured our attention.

Polystichum acrostichoides (Christmas fern) dotted the forest floor and along the trail. Most of the plants we saw were older, their fronds and pinnae ragged and tattered. A young individual, however, captured our eye, partly because of its fresh, bright green foliage and partly because of the close association with Polytrichum commune (common haircap moss), Flavoparmelia baltimorensis (rock greenshield lichen), and an unidentified fruticose lichen—a natural mini-terrarium.

Further along the trail, a patch of Thuidium delicatulum (delicate fern moss) was found thriving in the cold, wet conditions. As the name suggests, the leaves of this moss resemble the fronds of a small fern but form colonial mats rather than arising from a basal rosette as in true ferns. Wet conditions such as existed today are ideal for seeing this moss in its most attractive state—under dry conditions, the leaves are more appressed and contracted against the central stems.

As we descended the hillside, running water could be heard in the distance, suggesting we would be treated to the sight of a waterfall. At the bottom, the normally dry creek ran full, water crashing over the rhyolite boulders strewn further up the ravine and gushing down below us. Some careful footwork was required to scale the hillside off-trail to reach the water’s edge and get a closeup and personal view, but experience made the careful footwork down the hillside and back up well worth the effort.

Approaching the glades on Russell Mountain, the diversity of conspicuously green lichens and mosses immediately caught our attention. The normally xeric landscape was lush and moist—water pooling in depressions of the exposed rhyolite bedrock and stream over its slopes in sheets. Beds of Polytrichum commune (common haircap moss) colonized the edges of exposed bedrock, forming extensive mats of turgid, bright green, bristly vertical stems that looked like miniature primordial forests. Like Thuidium delicatulum (delicate fern moss), this moss also is more attractive when moist, its leaves widely spreading and straight, while in dry conditions they are erect with their tips often recurved.

The final leg of the hike took us through the scenic rhyolite glades (more properly called xeric rhyolite prairie) between the Ozark Trail and the Russell Mountain Trailhead. Normally, the glades are a harsh habitat—dry grasses crackling underfoot amid the searing heat and the surrounding forest of Quercus shumardii (Shumard’s oak) and Carya ovata (shagbark hickory) stunted and open. Today, however, dense fog, heavy air, and water running over every surface made the glade seem mysteriously soft and gentle.

The exposed rhyolite bedrock here represents remnants of volcanic rock formed 1.5 billion years ago. Representing one of the oldest continuously exposed landforms in North America, these craggy hills are but mere nubs of mountains that soared 15,000 feet above the salty Cambrian waters that lapped at their feet. It is only reasonable that these ancient rocks should be so heavily colonized by lichens—ancient life forms themselves resulting from a symbiotic association between fungi and a photosynthetic partner, usually algae or cyanobacteria (blue-green algae).

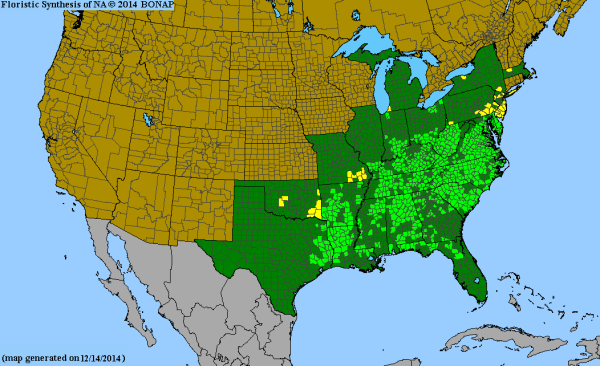

Like the previously seen mosses, rain brings out the best in lichen attractiveness—their hydrated tissues at their brightest and most colorful. A number of fruticose and foliose lichens can be found intermingling in the exposed rhyolite surfaces, with Flavoparmelia baltimorensis (rock greenshield lichen) being one of the most conspicuous examples of the latter.

©️ Ted C. MacRae 2021