In refreshing contrast to the more usually heard reports of declining and extinct species, a new paper by Dave Brzoska, Barry Knisley, and Jeffrey Slotten (Brzoska et al. 2011) announces the rediscovery of a tiger beetle previously regarded as probably extinct. Cicindela scabrosa floridana was described from a series of unusually greenish specimens collected in Miami, Florida in 1934; however, no additional specimens turned up in the following 70+ years despite dedicated efforts in the late 1980s and early 1990s by Brzoska, Knisley, and Ron Huber to locate and search areas around the presumed type locality. This paucity of specimens and occurrence of the type locality in highly urbanized Miami had caused most contemporary tiger beetle researchers to presume that the population had fallen victim to the ceaseless sprawl of urbanization and its attendant habitat destruction. However, in September of 2007, co-author Jeff Slotten, working with David Fine, rediscovered a population of individuals matching the type series while surveying butterflies in pine rockland habitat in the Richmond Heights area of Miami. Subsequent surveys of pine rockland habitat in surrounding areas revealed populations of the beetle at three sites – all in the Richmond Heights area.

In refreshing contrast to the more usually heard reports of declining and extinct species, a new paper by Dave Brzoska, Barry Knisley, and Jeffrey Slotten (Brzoska et al. 2011) announces the rediscovery of a tiger beetle previously regarded as probably extinct. Cicindela scabrosa floridana was described from a series of unusually greenish specimens collected in Miami, Florida in 1934; however, no additional specimens turned up in the following 70+ years despite dedicated efforts in the late 1980s and early 1990s by Brzoska, Knisley, and Ron Huber to locate and search areas around the presumed type locality. This paucity of specimens and occurrence of the type locality in highly urbanized Miami had caused most contemporary tiger beetle researchers to presume that the population had fallen victim to the ceaseless sprawl of urbanization and its attendant habitat destruction. However, in September of 2007, co-author Jeff Slotten, working with David Fine, rediscovered a population of individuals matching the type series while surveying butterflies in pine rockland habitat in the Richmond Heights area of Miami. Subsequent surveys of pine rockland habitat in surrounding areas revealed populations of the beetle at three sites – all in the Richmond Heights area.

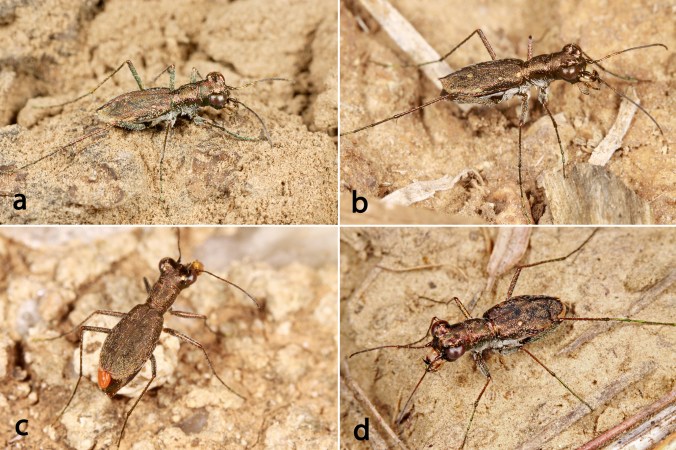

Source: Brzoska et al. (2011)

Cicindela scabrosa floridana was originally described by Cartwright (1939) as a variety of the broadly distributed southeastern U.S. species C. abdominalis. In describing the closely related C. highlandensis (endemic to the Lake Wales Ridge of central Florida), Choate (1984) also elevated the peninsular Florida-endemic C. scabrosa (previously considered a subspecies of C. abdominalis) to full species status and treated floridana as a subspecies of scabrosa, apparently due to the similarity of their elytral sculpturing, occurrence in both of dense flattened setae on the pronotum, and their allopatric distributions. The new availability of additional specimens of floridana, however, has allowed more detail comparisons of this form with scabrosa. In addition to the markedly greener elytra, the great majority of floridana lack post-median marginal spots – found consistently in scabrosa, and the apical lunule is generally thinner in floridana than in scabrosa. Moreover, no floridana were found to exhibit the vestigial middle band that scabrosa often exhibits, and the leg color of floridana also is lighter and more yellow than most scabrosa specimens. Differences in habitat, distribution and seasonality were also noted – scabrosa occurs in sand pine scrub habitat throughout most of peninsular Florida north of Miami from late spring to mid-summer, while floridana occurs only in pine rockland habitats in southern Florida with adults active well into October. These consistent differences in morphology, distribution, habitat, and seasonality led Brzoska et al. to elevate floridana to full species status. According to the most recent classifications of North American and Western Hemisphere tiger beetles (Pearson et al. 2006, Erwin and Pearson 2008), the new name would be Cicindela (Cicindelidia) floridana. However, Brzoska et al. follow the classification initially proposed by Rivalier (1954) and followed by Weisner (1992) in regarding Cicindelidia as a full genus, resulting in the new combination Cicindelidia floridana. The character differences identified by Brzoska et al. are illustrated with detailed photographs and presented in a key to allow recognition of the now four species in the abdominalis group.

The rediscovery of a rare species thought to be extinct is always cause for celebration. However, there is much work still to be done before prospects for the long-term survival of C. floridana can be considered secure. Many potential scrub and pine rockland sites throughout Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach Counties were identified and surveyed after the initial discovery of C. floridana in the Richmond Heights area. Unfortunately, to date the beetle has been found only at three sites in the Richmond Heights area. This suggests that C. floridana populations are small, highly localized, and greatly restricted in distribution, making the species a likely candidate for listing as endangered by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. To their credit, the authors have not revealed the precise locations of these sites, which will hopefully reduce the temptation by those with more philatelic tendencies to undercut ongoing studies of the distribution, abundance, biology, and habitat of C. floridana. These studies will be critical in the development of effective conservation strategies to ensure that this highly vulnerable representative of Florida’s natural heritage does not, once again, become regarded as extinct.

REFERENCES:

Brzoska, D., C. B. Knisley, and J. Slotten. 2011. Rediscovery of Cicindela scabrosa floridana Cartwright (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) and its elevation to species level. Insecta Mundi 0162:1–7.

Cartwright, O. L. 1939. Eleven new American Coleoptera (Scarabaeidae, Cicindelidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 32: 353–364.

Choate, P. M. 1984. A new species of Cicindela Linnaeus (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) from Florida, and elevation of C. abdominalis scabrosa Schaupp to species level. Entomological News 95:73–82.

Erwin, T. L. and D. L. Pearson. 2008. A Treatise on the Western Hemisphere Caraboidea (Coleoptera). Their classification, distributions, and ways of life. Volume II (Carabidae-Nebriiformes 2-Cicindelitae). Pensoft Series Faunistica 84. Pensoft Publishers, Sofia, 400 pp.

Pearson, D. L., C. B. Knisley and C. J. Kazilek. 2006. A Field Guide to the Tiger Beetles of the United States and Canada. Oxford University Press, New York, 227 pp.

Rivalier, E. 1954. Démembrement du genre Cicindela Linne, II. Faune americaine. Revue Francaise d’Entomologie 21:249–268.

Wiesner, J. 1992. Checklist of the Tiger Beetles of the World. Verlag Erna Bauer; Keltern. 364 pp.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2011