At the beginning of the season I was planning to spend the first week of June collecting insects in southeastern New Mexico. Family issues intervened, however, and left me with a week of vacation time and no plans on how to use it. I’ve never been one to not use vacation time, so I quickly came up with a backup plan—a Friday here and a Monday there to create several 3–4 day weekends. Long weekends may not allow travel to far off and exotic places, but they do allow me to travel a bit further than I would for a regular weekend. I also took advantage of my frequent travel for work to stop off at favorite collecting sites for an evening of blacklighting (much more fun than sitting in a hotel room) or a half-day in the field before getting back home. I always have my big camera with me for serious insect photography when the opportunity arises, but I also take frequent iPhone snapshots to document the “flavor” of my time in the field. In previous years, I’ve collected snapshots from my extended trips into “iReports”, which were later followed by posts featuring subjects that I spent “quality camera time” with (see 2013 western Oklahoma, 2013 Great Basin, and 2014 Great Plains). I’ve decided to do the same thing now, only instead of a single trip this report covers an entire summer. I realize few people have the patience for long-reads; nevertheless, enough readers have told me that they like my trip reports and all of their gory details to make this a worthwhile exercise. If you’re not among them, scan the photos—all of which were taken with a stock iPhone 5S and processed using Photoshop Elements version 11—and you’re done!

Searching for the Ghost Tiger Beetle

Central/Northwest Missouri (12–14 June 2015)

In mid-June my good friend, colleague, and fellow cicindelophile Chris Brown and I followed the Missouri River Valley across the state and and up along its northwestern border to visit previously known and potentially new sites for Ellipsoptera lepida—the Ghost Tiger Beetle. We first saw this lovely white species back in 2000 while visiting some of the large sand deposits laid down in central and east-central Missouri by the 1993 flood. In the years since these sites have become increasingly encroached by forests of eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides), making them less and less suitable for the beetle (it also remains one of only two tiger beetles known to occur in Missouri that I have not yet photographed). In the meantime several new sand deposits have been laid down in northwestern Missouri by flooding in 2011, so the question has come up whether the beetle has yet occupied these new sites. We started out at a couple of potentially new sites in east-central Missouri (and did not find the beetle), then went to one of two known sites in central Missouri. We did not find the beetle there either, but we did find this eastern hognose snake (Heterodon platirhinos).

Eastern hognose snake (Heterodon platirhinos) | vic. Eagle Rock Conservation Area, Boone Co.

Hognose snakes are well known for their vaired repertoire of defensive behaviors—from flattening of the head and hissing to rolling over and playing dead (a behavior called thanatosis)—the latter behavior often accompanied by bleeding from the mouth and even defecating onto itself. This one, however, was content to simply flatten its head and hiss, its tongue constantly flickering.

The flattened head is an attempt by the snake to make itself appear larger and more imposing.

Standing its ground as tenaciously as it did, I took advantage of the opportunity to close in tight and take a burst series of photos, which I used to create this animated gif of the snake’s constantly flickering tongue.

After an evening of driving to northwest Missouri and a stay in one of our favorite local hotels (eh hem…), we awoke to find the scene below at our first destination.

Ted MacRae & Chris Brown look out over a flooded Thurnau Conservation Area, Holt Co.

No tiger beetles there! What to do now. One thing I love about modern times is the ability to pull out the smart phone and scan satellite images of the nearby landscape. Doing this we were able to locate a large sand deposit just to the south and navigate local, often unmarked roads to eventually wind up at a spot where we could access the area on foot. But before we did this we needed gas, and the only gas station for miles was a Sinclair station with a bona fide, original green dinosaur—one of the most potent and iconic corporate symbols ever! I remember these from my childhood, but this is the first one I’ve seen in years.

An authentic Sinclair dinosaur guards the only gas station for miles.

Rain the night before had made the roads muddy, and it was only with some difficulty that we finally located a way to access the sand deposits we had seen on the satellite images. Even then we needed to hike a half-mile to access the sand plain, but once we got there this is what we saw:

Sand plain deposited 2011 along Missouri River, Thurnau Conservation Area, Holt Co.

At first we were optimistic—the habitat looked perfect for not only E. lepida but also the more commonly seen Cicindela formosa generosa (Eastern Big Sand Tiger Beetle) and, at least in this area, C. scutellaris lecontei (LeConte’s Tiger Beetle). We saw no adults however, as we searched the plain, and we wondered if the cool, cloudy conditions that lingered from the previous evening’s storms were suppressing adult activity. After awhile, however, we noted that we hadn’t even found evidence of larval burrows, and that is when we began to think that maybe four years wasn’t long enough for populations to establish in such a vast expanse of new habitat. Eventually Chris did find a single E. lepida adult—a nice record but certainly not evidence of a healthy population.

Seemingly perfect habitat, but void of active adults or evidence of larval burrows.

The next sand plain we visited was a little further north at Corning Conservation Area, also in Holt Co. and also laid down by the 2011 flood. Once again we saw no active tiger beetles in the area, and by this point we were convinced that the species were not just inactive but had not yet even colonized the plains. It should be noted that large sand expanses such as these actually are not exactly a natural process, but rather the result of river channeling and the use of levees to protect adjacent farmland. Before such existed, the river existed as an intricate system of braided channels that rarely experienced catastrophic flooding. Nowadays, with the river confined to a single, narrow channel, the river valley doesn’t experience a normal ebb and flow of water. Only when water levels reach such extreme levels in the narrow channel that they breach a levee does the adjacent valley flood, with the area immediately downstream from the levee breach receiving huge amounts of sand and mud scoured from the breach zone. Tiger beetle species adapted to ephemeral sand plain habitats along big rivers probably

Another sand plain deposited in 2011 at Corning Conservation Area, Holt. Co.

Cottonwoods and willows were already colonizing the edge of the plain, and the latter were heavily infested by large blue leaf beetles. As far as I know the only species of Altica in Missouri associated with willow is A. subplicata, although admittedly it is a large, diverse genus and there could be other willow-associates within the state that I am unaware of. The beetles seemed especially fond of the smaller plants (1–3′ in height), while taller plants were relatively untouched.

Altica subplicata? (willow flea beetle) | Holt Co., Missouri

Beetles congregated heavily on smaller willow plants.

Despite the heavy adult feeding we could find no larvae on the foliage.

Few other insects were seen. I did see a large, standing, dead cottonwood (Populus deltoides) and checked it out hoping hoping to find a Buprestis confluenta adult or two on its naked trunk (a species I found for the first time last year and still have yet to find in Missouri, although it is known from the state). No such luck, but I did collect a couple of large mordellids off of the tree. Let me say also that there were some interesting other plants in the area…

Wild hemp (Cannabis sativa)

After satisfying ourselves that Corning also was not yet colonized by the tiger beetles, we drove further north into Atchison Co., the northwesternmost county in the state, to check out one more sand plain deposited by the 2011 flood at Nishnabotna Conservation Area. The sand plain at this area was much smaller than the two previous plains we had visited, and it was also far less accessible, requiring a bushwhacking hike through thick vegetation that was quite rank in some areas. Nevertheless, we soldiered on, motivated by the hope that maybe the third time would be a charm and we would find the beetles that we were searching for. The hike was not all bad—eagles were abundant in the area, and in one distant tree we could see a female perched near her nest with two large nestlings sitting in it. The passing storm system and sinking sun combined to create a rainbow that arched gracefully over the tree with the nest, resulting in one of the more memorable visions from the trip.

Rainbow over eagle’s nest (tree is located at left one-third of photo).

By the time we got close enough to get a better photograph of the nest the female had departed, but the two nestlings could still be seen sitting in the nest. Sadly, the rather great effort we made to hike to the sand plain was not rewarded with any tiger beetles, and in fact the sand plain was little more than a narrow, already highly vegetated ridge that will probably be completely encroached before the tiger beetles ever find it.

Eagles in nest

Ellipsoptera lepida was not the only tiger beetle we were hoping to see on the trip. The Sandy Stream Tiger Beetle, E. macra, has also been recorded from this part of the state, and being members of the genus Ellipsoptera both species can be attracted to lights at night. In one last effort to see either of these species, we went to Watson Access on the Nishnabotna River, near its confluence with the Missouri River. Thunder clouds retreating to the east were illuminated by the low hanging sun to the west, creating spectacular views in both directions. Unfortunately, the insect collecting at the blacklights after sunset was not near as interesting as the sky views that preceded it.

Sunset lit thunderclouds to the east…

… and a bright colored sunset to the west on the Nishnabotna River, Atchison Co.

The next day we had to start making our way back to St. Louis. But while we were in the area we decided to check on the status of one of Missouri’s rarest tiger beetles, Parvindela celeripes (formerly Cylindera celeripes)—the Swift Tiger Beetle. Not known to occur in Missouri until 2010, this tiny, flightless species is apparently restricted in the state to just three small remnants of loess hilltop prairie in Atchison and Holt Counties. We were close to one of these—Brickyard Hill Conservation Area (where Chris and I first discovered the beetles) so stopped by to see if adults were active and how abundant they were. To our great surprise, we found adults active almost immediately upon entering the site, and even more pleasantly surprising the adults were found not just in the two small areas of the remnant where we had seen them before but also in the altered pasture (planted with brome for forage) on the hillside below the remnant (foreground in photo below). This was significant in our minds, as it was the very first time we have observed this beetle in substantially altered habitat. The beetle was observed in relatively good numbers as well, bolstering our hopes that the beetles were capabale of persisting in these small areas and possibly utilized altered pastureland adjacent to the remnants.

Brickyard Hill Conservation Area, loess hilltop prairie habitat for Parvindela celeripes

As we made our way back towards St. Louis, there was one more site created by the 1993 flood where we observed E. lepida in the early 2000s that we wanted to check out and see how the beetle was doing. In the years since we first came to Overton Bottoms, much of its perimeter has converted to cottonwood forest; however, a large central plain with open sand exposures and bunch grasses persists—presumably providing acceptable habitat for the species. Chris had seen a few beetles here in a brief visit last summer, but this time we saw no beetles despite a rather thorough search of the central plain. It seemed untenable to think that the beetles were no longer present, and we eventually decided (hoped) that the season was still too young (E. lepida is a summer species, and the season, to this point, had been rather cool and wet). The photos below show what the central plain looks like—both from the human (first photo) and the beetle (second photo) perspective. I resolved to return later in the month to see if our hunch was correct.

Big Muddy NFWR, Overton Bottoms, south unit, sand plain habitat for Ellipsoptera lepida

A tiger beetle’s eye view of its sand plain habitat

It doesn’t happen often, but every now and then I get caught by rain while out in the field, and this time we got caught by a rather ominous thunderstorm. The rain didn’t really become too heavy until shortly before we reached the car, but the lightning was a constant concern that made bushwhacking back more than a mile through thick brush one of the more unnerving experiences that I’ve had to date.

Trying for Prionus—part 1

South-central Kansas (26–29 June 2015)

Last summer Jeff Huether and I traveled to several locations in eastern Colorado and New Mexico and western Oklahoma to find several Great Plains species of longhorned beetles in the genus Prionus using recently developed lures impregnated with prionic acid—a principal sex pheromone component for the genus. These lures are extraordinarily attractive to males of all species in the genus, and on that trip we managed to attract P. integer, P. fissicornis, and P. heroicus and progress further in our eventual goal to collect all of the species in the genus for an eventual molecular phylogenetic analysis. One species that remains uncollected by pheromones (or any other method) is P. simplex, known only from the type specimen labeled simply “Ks.” A number of Prionus species in the Great Plains are associated with sand dune habitats, so we had the idea that maybe P. simplex could be found at the dunes near Medora—a popular historical collecting site, especially with the help of prionic acid lures. Perhaps a long shot, but there’s only one way to find out, so we contacted scarab specialist Mary Liz Jameson at Wichita State University, who graciously hosted Jeff, his son Mark Huether, and I for a day in the field at Sand Hills State Park. We didn’t expect Prionus to be active until dusk, during which time we planned to place lure-baited pitfall traps and also setup blacklights as another method for attracting the adult males (females don’t fly). Until then, we occupied ourselves with some day collecting—always interesting in dune habitats because of the unique sand-adapted flora and the often unusual insects associated with them.

Sand Hills State Park (“Medora Dunes”), Kansas

Milkweeds (genus Asclepias) are a favorite of mine, and I was stunned to see a yellow-flowered form of butterfly milkweed (A. tuberosus). Eventually I would see plants with flowers ranging from yellow to light orange to the more familiar dark orange that I know from southern Missouri. I checked the plants whenever I saw them for the presence of milkweed beetles, longhorned beetles in the genus Tetraopes (in Missouri the diminutive T. quinquemaculatus is most often associated with this plant), but saw none.

Asclepias tuberosus “yellow form”

In the drier areas of the dunes, however, we began to see another milkweed that I recognized as sand milkweed (A. arenicola). I mentioned to Jeff and Mary Liz that a much rarer species of milkweed beetle, T. pilosus, was associated with this plant and to be on the lookout for it (I had found a single adult on this plant at a dune in western Oklahoma a few years back). Both the beetle and the plant are restricted to the Quaternary sandhills of the midwestern U.S., and within minutes of me telling them to be on the alert we found the first adult! During the course of the afternoon we found the species to be quite common in the area, always in association with A. arenicola, and I was happy to finally have a nice series of these beetles for my collection.

Two Sandhills specialties—Tetraopes pilosus on Asclepias arenaria

Milkweed beetles weren’t the only insects associated with sand milkweed in the area—on several plants we saw Monarch butterfly larvae, some nearing completion of the larval stage as the one shown in the photo below. Monarchs have been in the news quite a bit lately as their overwintering populations show declines in recent years for reasons that are not fully understood but may be related to recent droughts diminishing availability of nectaring plants for migrating adults and reduction of available food plants as agricultural lands in the U.S. become increasingly efficient.

Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) larva on Asclepias arenaria

We found some other interesting insects such as the spectacular Plectrodera scalator, cottonwood borer, and the southern Great Plains specialty scarab, Strigoderma knausi, both of which I took the time to photograph with the big camera—separate posts on those species will appear in the future. Sadly, no Prionus came to either our lures or our lights that evening, but some interesting other insects were seen during the day and even at the lights despite unseasonably cool temperatures and a bright moon. I’ll post photographs of these insects, taken with the “big” camera, in the coming weeks. In the meantime, my thanks to Mary Liz for hosting us—I look forward to our next chance to spend some time in the field together.

Ted MacRae shows Mark Huether, Jeff Huether, and Mary Liz Jameson how to take a panoramic selfie.

The following day, Adam James Hefel—at the time a graduate student at Wichita State University—and I traveled northwest of Wichita to Quivira National Wildlife Refuge. Adam has recently become interested in tiger beetles and had observed several interesting species on the margins of the salt marshes at Quivira. Several of these species were on my “still to photograph” list (and one even on my “still to see” list), so I was happy to have access to some local knowledge to help me

Quivira NWR – salt marsh habitat for halophilic tiger beetles

The saline flats of the central U.S. are hyperdiverse for tiger beetles. Adam has seen six species in the saling flats of Quivira, including the saline specialists Cicindela fulgida, C. wllistoni, Ellipsoptera nevadica knausi, Eunota togata, and E. circumpicta johnsonii (formerly Habroscelimorpha) (both red and green forms) and the ubiquitous Cicindelidia punctulata. We managed to find all of these except C. willistoni, which is a spring/fall species—unusual for a saline specialist, but the extreme heat of the day made them exceedingly difficult to approach (and virtually impossible to photograph).

Tiger beetles are found most often in alkaline flats with sparse vegetation

The wide open central flats are devoid of not only vegetation but tiger beetles (and life in general!).

Ever fascinated by the diversity of milkweeds to be found in the central U.S., an unfamiliar Asclepias growing in the higher, drier areas around a salt marsh caught my attention. Of course, I checked them for milkweed beetles and quickly found a number of Tetraopes tetraophthalmus individuals. kindly identified the milkweed from my photos as Asclepias speciosa (showy milkweed), which does not occur in Missouri (hence the reason I was not familiar with it) but that gets common in the Great Plains and foothills of the Rocky Mountain.

Asclepias speciosa, or showy milkweed.

The specific epithet “specioosa” refers to the large, showy flowers.

Tiger beetles were not the only wildlife encountered on the saline flats. Killdeer and western snowy plover adults were abundant in the area, and we found this next with eggs along the lightly vegetated edge of a saline flat around Big Salt Marsh. suggested they are probably plover eggs, since killdeer don’t usually scrape out a cup or put debris around the eggs, while snowy plovers are known to nest on or near salt flats and frequently surround their eggs with twigs, small bones or other debris.

Western snowy plover (Charadrius nivosus) nest with eggs at the edge of an open flat

During the drive into the refuge, I noted several stands of large cottonwood (Populus deltoides), many of which were half- or completely dead. To some, these trees may be just ugly, half-dead trees. For me, however, they offer an opportunity to look for the gorgeous and rarely encountered Buprestis confluens, a species which I found for the first time just last year (not too far from hear in north-central Oklahoma). After getting our fill of tiger beetles, we drove to a parking lot surrounded by some of these trees, and even before I got out of the car I could see an adult B. confluens sitting on the trunk of a large, dead tree at the edge of the parking lot! I quickly secured the specimen, then spotted the half-dead tree in the photo below and walked towards it to look for more. I did not see any adults sitting on the trunk, but what I did see was truly incredible—two adults just beginning to emerge from the trunk! Waiting for one of the adults to emerge naturally (we “helped” the other one along) and photographing the sequence would occupy the next hour, but what an experience (and, of course, photos to come in a separate post).

This large, half-dead Populus deltoides “screams” Buprestis confluenta!

Wild hemp (Cannabis sativa) fills the are with a pungent aroma.

After a break from the heat and something to eat in the nearest town (20 miles away), I returned to the cottonwoods, broke out the hatchet, and began chopping. Cottonwood is an amazingly soft wood compared to hardwoods such as oak and hickory, but dead cottonwood is still tough, and only after much effort did I manage to chop out two pupae (one of which later successfully emerged as an adult) and two unemerged adults, resulting in a nice, if still rather small, series of a species that until last year was not represented in my collection and until this time by only a single specimen.

Chopping Buprestis confluenta unemerged adults/pupae

Exposed Buprestis confluenta pupa in its pupal chamber.

With the setting sun illuminating distant thunderclouds, I returned to the salt marshes to setup blacklights for the evening in hopes of attracting some of the tiger beetles that we had seen earlier in the day—not in attempt to collect more specimens, but rather to take advantage of their attraction to the lights and reduced skittishness in the cool, night air in an attempt to photograph them (I already had live specimens for studio photographs if necessary, but I prefer actual field photographs whenever possible). Eunota togata was not attracted to the lights, but both E. nevadica knausi and E. circumpicta johnsonii came to the lights in numbers (both red and green forms of the latter), and I succeeded in getting some real nice photographs as a result.

Thundercloud illuminated by setting sun

On the way back home, and again with the sun dropping close to the horizon, I stopped by Overton Bottoms again to look for Ellipsoptera lepida. Chris and I hadn’t see it here two weeks ago, and I was thinking (hoping) that it might have still a bit early in the season. This time I found them, and although they were not numerous and were apparently confined to the southernmost exposures of the central sand plain, they were still plentiful enough to allow me to get the field shots that I’ve wanted of this species for so long (and providing fodder for yet another future post). This species never seems to be encountered in great numbers, and although I have seen them on a number of occasions it always amazes me just how difficult they are to see!

Another pass through Overton Bottoms looking for Ellipsoptera lepida, this time with success!

Tryin’ for Prionus—part 2

South-central Kansas (11–12 July 2015)

Although our long-shot effort for Prionus simplex at the dunes near Medora, Kansas didn’t pan out, another species we hoped to see was P. debilis—a rather uncommonly collected species that occurs in the tallgrass prairies of the eastern Great Plains and, to our knowledge, had not yet been demonstrated to be attracted to prionic acid. I’d only seen this species once myself, some 30 years ago when I collected four males at lights near the southwestern edge of Missouri. As it happens, longtime cerambycid collector Dan Heffern grew up in P. debilis-land near Yates Center—not too far from where we were just a few weeks ago. When I mentioned my search for the species, he told me how commonly he used to see it around his home—especially around the 4th of July—and put me in contact with a friend who still lives in the area and has several tallgrass prairie remnants on his land. I made arrangements to visit the following weekend, and with prionic acid impregnated lures in the cooler and blacklights and sheets in the cargo area I set off. As I passed south through eastern Kansas I began to see nice tallgrass prairie remnants about 20 miles from my destination, so I took a chance and set a trap as a backup in case things didn’t pan out near Yates Center.

Trap baited with prionic acid lure

Things did pan out, however, although for a long time it did not appear they would. Dan’s friend kept me company while I placed a couple of traps and setup the blacklights, and for a couple of hours after sunset no beetles were seen (although we did enjoy good beer and better conversation). Just when I was ready to throw in the towel I saw a male crawling on the ground near one of the lights, and over the course of the next hour I found nearly a dozen males crawling on the ground in the general area around the lights but never actually at the lights. Interestingly, no males were actually seen in flight, nor were any attracted to the trap placed near one of the lights; however, after I took down the lights and checked the other trap there were five males in it. This likely represents the first demonstration of attraction to prionic acid by males P. debilis. I brought a couple of live males home for photography, taking this iPhone shot of a sleeping beetle in the meantime.

Prionus debilis “sleeping”in its cage after being taken near an ultraviolet light

One the way back home the next morning, success already “in the bag”, I stopped to check the trap I had placed the previous day. Filled with anticipation as I approached the trap, I was elated to find 21 males in the trap!

Prionus debilis in prionic acid lure-baited trap

The male antennae of this and other Prionus species show numerous adaptations that are all designed to maximize the ability to detect sex pheromones emitted into the air by females. They are both hyper-segmented and flabellate, providing maximum surface area for poriferous areas filled with chemical receptors. Larval habits for this species remain unknown, but Lingafelter (2007) states “Larvae may feed in living roots of primarily Quercus and Castanea, but also Vitis, Pyrus, and Zea mays.” I am not sure of the source of this information and don’t really believe it, either, as I think it much more likely that they feed on roots of bunch grasses such as bluestems (Andropogon spp.) and other grass species common in the tallgrass prairies.

Prionus debilis “looking” out over its tallgrass prairie habitat

Before reaching St. Louis, I decided to stop off at the last two known sites for Missouri’s endangered (possibly extirpated), disjunct, all-blue population of Eunota circumpicta johnsonii (Johnson’s Tiger Beetle). This didn’t go well—I first tried Blue Lick Conservation Area in Cooper County, where Chris Brown and I made the last known sighting of this beetle in the state 12 years ago at a salt spring about 500 yards further down the road in the photo below. I’m unsure what adaptations adults and larvae may have for surviving prolonged flooding, but it certainly cannot be helpful for the beetle. I then visited nearby Boone’s Lick State Historic Site in Howard County, and while the site was not flooded the two small areas where salt springs were located during our survey were even more heavily encroached by vegetation than before. Not only were no beetles seen, there did not even seem to be the slightest possibility that beetles could occur there. I keep hoping that the beetle will, someday, be seen again, but in reality I think I am just having trouble accepting the fact that I may have actually witnessed the extirpation of this incredibly beautiful and unusual population of beetles.

Flooded road leading to last known Missouri site for Eunota circumpicta johnsonii

Chillin’ after work

Sand Prairie – Scrub Oak Preserve, central Illinois (15 July 2015)

By the time mid-July rolls along, temperatures are not the only thing heating up. My travel for work also reaches a fever pitch as I begin traveling to research plots in Illinois and Tennessee every two weeks. It takes three days to make the +1,000-mile round trip, which means that I have two nights and an occasional afternoon stop to collect insects—much more fun than checking into hotel right after work, eating dinner at Applebee’s, and spending the evening switching back and forth between FOX and MSNBC to see who can make the most outrageous statement because IFC just isn’t offered. One of my favorite spots along this route to set up a blacklight is Sand Prairie – Scrub Oak Preserve in Mason County, Illinois. Nothing too spectacular showed up at the lights there this season, but as they say a bad day (or night) of bug collecting is better than a good day of just about anything else.

Calling all insects—the blacklight awaits you!

On this particular night a number of hawk moths (family Sphingidae) came to the lights, among the prettier of which included this Paonias excaecata (blinded sphinx) (kindly identified by .

Paonias excaecata (blinded sphinx) | Sand Prairie – Scrub Oak Preserve, Mason Co., Illinois

More chillin’ after work

Pinewoods Lake, southeast Missouri (28 July 2015)

Another species of Prionus that I hadn’t seen for many years was P. pocularis, a species found in the pineywoods across the southeastern U.S. and, thus, reaching its northwestern distributional limits in the shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata) forests of the Ozark Highlands in southern Missouri. Like P. debilis, I had only seen this species once before—two males at a blacklight at Pinewoods Lake National Forest Recreation Area in Carter County many years ago. Unlike P. debilis, however, these were seen later in summer, as were a few other specimens known from the state. That being the case, I decided to try the prionic acid lures at Pinewoods Lake while traveling back up from Tennessee. I arrived at the lake shortly before sunset and, after getting the traps put out and the lights setup, had the chance to look out over the lake and its surrounding forests where I had collected so many insects back in the 1980s as a young, eager, budding coleopterist.

Pinewoods Lake at dusk

Quite some time passed and no Prionus beetles were seen at the light or in the trap (but several other longhorned beetles did occur). Recalling my experience with P. debilis in Kansas a few weeks earlier, I remained hopeful, and eventually my optimism was rewarded when I found this single male floating in the trap’s ethanol preservative. Curiously, it would be the only male seen that night, although several individuals of the related and much more common P. imbricornis were attracted to the prionic acid lures.

Prionus pocularis in prionic acid lure-baited trap | Pinewoods Lake, Carter Co., Missouri

Several other insects did come to the blacklights, among the more photogenic being this underwing moth (genus Catacola, family Noctuidae) identified by as Catocala neogama.

Catocala neogama at ultraviolet light | Pinewoods Lake, Carter Co., Missouri

Even more photogenic than underwings are royal moths (family Saturniidae), including this imperial moth, Eacles imperialis.

Eacles imperialis (imperial moth) at ultraviolet light | Pinewoods Lake, Carter Co., Missouri

Among the longhorned beetles I mentioned that did come to the lights was this Orthosoma brunneum (brown prionid). This species is closely related to prionid beetles (both are in the subfamily Prioninae). However, it is not a member of the genus Prionus, and, thus, is not attracted to prionic acid. It is perhaps no coincidence that males of this species do not exhibit the hypersegmentation and flabellate modifications of their antennae possessed by males in the genus Prionus, though they may still rely on sex pheromones for locating females.

Orthosoma brunneum at ultraviolet light | Pinewoods Lake, Carter Co., Missouri

Even spiders were coming to the blacklights, perhaps attracted not by the light itself but by the ready availability of potential prey.

Latrodectus mactans (black widow) at ultraviolet light | Pinewoods Lake, Carter Co., Missouri

Cicadamania!

White River Hills region, southwest Missouri (1–2 August 2015)

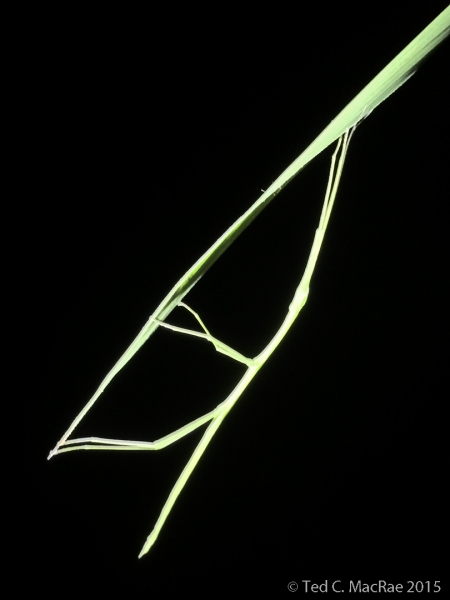

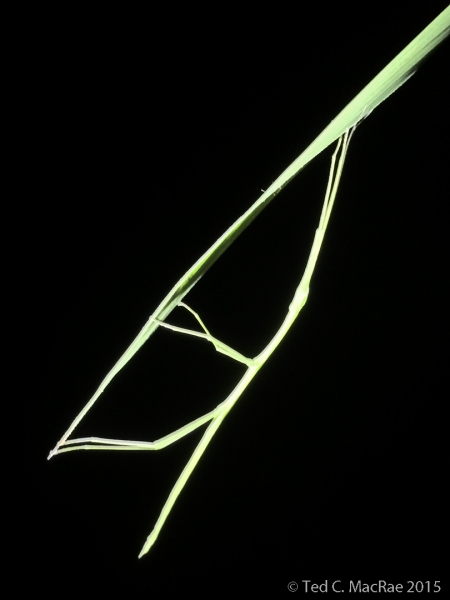

Although I had succeeded in finding Prionus pocularis earlier in the week at Pinewoods Lake, I wasn’t satisfied with having found just a single individual. I had nothing on the calendar the following weekend, so I decided to make a run down to one of my favorite areas in all of Missouri—the White River Hills of extreme southwest Missouri. The only other record of the species in Missouri is from that area, with its abundance of shortleaf pine forests (the species breeds in decadent pines), and I though how nice it would be to find more individuals in a part of the state that I love so much. The plan was to drive down, set a prionic acid trap or two once I got into the pine forests of the area, and then find a good spot to setup some blacklights with one more prionic acid trap that I could monitor. The plan was executed perfectly, and I ended up setting up the lights on a ridge just south of Roaring River State Park; however, the beetles never came. Nevertheless, like I said earlier a bad day/night of bug collecting is still better than just about anything else, and there was plenty at and near the lights to keep the night interesting. Once was this tiny walkingstick nymph that I found hanging out at the tip of a blade of grass. I was intrigued by the rather peculiar position adopted by the resting animal, with its forelegs and antennae extended straight out in front of the body with their tips resting on the grass blade.

Undetermined walkingstick nymph | Mark Twain N.F., Barry Co., Missouri

One thing I love about blacklighting for insects is the sounds of the night—katydids fill the black night with raspy calls while Whip-Poor-Wills and their country cousins the Poor-Will’s-Widows hoot and cluck in the distance.

Undetermined katydid | Mark Twain N.F., Barry Co., Missouri

As I was photographing the walkingstick, I felt something crawling on my neck. After many years of doing this, I’ve learned not to freak out and slap wildly at something crawling on my neck, because 1) more often than not it is something interesting and 2) even if it isn’t particularly interesting it’s almost never capable of biting or stinging. Still, I don’t want to just grab it unseen or pin it against my neck—instead I kind of “scoop” it away with my fingers and toss it onto the ground beside me in one swift, assertive movement. This night’s mystery neck crawler was about as interesting as they get—Dynastes tityus (eastern Hercules beetle), the largest beetle in eastern North America. This one is a female by virtue of its lack of any horns on the head and pronotum.

Female Dynastes tityus (eastern Hercules beetle) | Mark Twain N.F., Barry Co., Missouri

After pulling the lights down for the night, I drove to Mincy Conservation Area, one of the many dolomite glades in the area in the next county over and one that I had not visited for some time. There are no hotels in the area, and my bones are a little too old to be sleeping on the ground, so I just pulled into the campground, took off my shoes, changed into PJs, and laid the driver’s seat all the way back for a surprisingly comfortable night’s sleep. My frugalness would have its reward, although I did not know it until I awoke early the next morning to a hauntingly beautiful fog. I’d never seen the glades in such manner—so serene. I knew the rising sun would quickly burn off the fog and and the moment would be lost if I didn’t act quickly, so I grabbed both big camera and iPhone and, put on some shoes (didn’t bother with changing out of my PJs), and walked the glade taking as many photos as I could. While the quality of the iPhone snaps doesn’t compare with those taken with the big camera, they nevertheless convey the quiet beauty of the glade.

Morning fog over the dolomite glade | Mincy Conservation Area, Taney Co., Missouri

Missouri coneflower (Rudbeckia missouriensis) is a characteristic plant of limestone and dolomite glades in the Ozark Highlands of southern Missouri.

Missouri coneflower (Rudbeckia missouriensis) | Mincy Conservation Area, Taney Co., Missouri

Morning dew makes spider webs abundantly conspicuous.

Morning fog on a spider web | Mincy Conservation Area, Taney Co., Missouri

Eventually the rising sun began to burn through the cool, damp fog, portending another day of searing heat in the xeric glade landscape.

The rising sun begins to burn off the fog | Mincy Conservation Area, Taney Co., Missouri

Heading back to my car as temperatures began to rise quickly, I was struck by the cacophony of cicadas that were already getting into high gear with their droning buzz calls. As I passed underneath one particular tree I noticed the song was coming from a branch very near my head. I like cicadas, but I was there to look for the spectacular Plinthocoelium suaveolens (bumelia borer), a glade species associated with gum bumelia (Sideroxylon lanuginosum). Had it been the song of a “normal” cicada like Neotibicen lyricen (lyric cicada) or N. pruinosus (scissor grinder cicada) I would have paid it no mind. It was, instead, unfamiliar and distinctive, and when I searched the branches above me I recognized the beautiful insect responsible for the call as Neotibicen superbus (superb cicada), a southwest Missouri specialty—sumptuous lime-green above and bright white pruinose beneath. I had not seen this spectacular species since the mid 1980s (most of my visits to the area have been in the spring or the fall rather than high summer), so I spent the next couple of hours attempting to photograph an individual in situ with the big camera. This is much, much easier said than done—the bulging eyes of cicadas give them exceptional vision, and they are very skittish and quick to take flight. I knew I had the iPhone photo shown below if all else failed, and for some time every individual I tried to approach ended up fluttering off with a screech before I could even compose a shot, much less press the shutter. Persistence paid off, however, and I eventually succeeded in locating, approaching, and photographing an unusually calm female resting at chest height on the trunk of a persimmon tree. Along the way I checked the gum bumelia trees hoping to spot one of the beautiful longhorned beetles associated with that tree, but none were seen.

Neotibicen superbus

It was already high noon by the time I finished up at the Mincy glades, so I began to retrace my steps to check the prionic acid traps that I had set out the day before. Along the way I stopped by Chute Ridge Glade Natural Area in Roaring River State Park, another place where I have seen bumelia borers, so I stopped to try my luck there before continuing on to pick up the traps. Again, none were seen, but in addition to numerous individuals of N. superbus I found another species of cicada, still undetermined by more robust and nearly blackish and with a throatier call that sounding a bit like a machine gun (or table saw hitting a nail!). Despite the lack of bumelia borers, I enjoyed my time on the glade immensely and eventually had to call it quits if I was to get to all of my traps before nightfall.

Still more chillin’ after work

Pinewoods Lake, southeast Missouri (11 August 2015)

Two attempts at Prionus pocularis in the past two weeks had netted me but a single specimen—this species was becoming my summer nemesis. So when I found myself back in Tennessee for field trial work and the timing still right I decided to spend the evening at Pinewoods Lake once again before heading back to St. Louis and see if the third time would be a charm. I found a new restaurant in the tiny nearby town of Ellsinore, and the dinner special that evening was fried catfish—hoo boy! My belly was in a good place after that, filling me with optimism that I would have success tonight. I got to the lake at dusk, quick setup the blacklights and put the prionic acid traps in place, and waited for the bugs to come in.

Pinewoods Lake at dusk, again!

The evening’s first visitor to the lights was a parandrine cerambycid—Neandra brunnea. Believe it or not, this was the first time I have ever seen the species alive (once before finding a dead specimen in a Japanese beetle trap waaaay back in the mid-1980s!)—a pretty nice find. In fact, Pinewoods Lake produced a number of good finds during those days back in the 1980s when I was collecting here regularly—longhorned beetles such as Acanthocinus nodosus, Enaphalodes hispicornis, and the aforementioned Prionus pocularis, male Lucanus elaphus stage beetles, the jewel beetle Dicerca pugionata on ninebark in the draws, and the seldom seen tiger beetle Apterodela unipunctata (formerly Cylindera unipunctata), just to name a few.

Neandra brunnea | Mark Twain N.F., Pinewods Lake, Carter Co., Missouri

Seeing N. brunnea and the prospects of collecting P. pocularis weren’t the only things putting me in a good mood…

Blacklighting is better with beer!

My optimism, unfortunately, would eventually prove to be unfounded, as not only did P. pocularis never show up—either at the blacklights or the prionic acid traps, no other beetles showed up as well, longhorned or otherwise. When that happens, I have no choice but to start paying attention to other insects that show up at the lights. It was slim pickings on this night for some reason, making this already striking moth identified by as Panthea furcilla (tufted white pine caterpillar or eastern panthea) in the family Noctuidae stand out even more so.

Panthea furcilla | Mark Twain N.F., Pinewoods Lake, Carter Co., Missouri

While walking between the blacklights and the prionic acid traps, something suspended between two trees caught my eye. I recognized it quickly as some type of orb weaver spider (family Araneidae), but I couldn’t exactly figure out exactly what was going on until I took a closer look and saw that there were actually two spiders! I’d never seen orb weaver courtship before, so I excitedly took a few quick shots with the iPhone and then hurried back to the car to get the big camera.

Be very, very careful boy!

Sadly, the male had already departed by the time I got back, so the quick iPhone photos I took are the only record I have of that encounter. Still, I got some good photos of just the female with the big camera, along with the quicker, dirtier iPhone shots—one of which is shown below. According to these are likely a species in the genus Neoscona.

Neoscona sp. | Mark Twain N.F., Pinewoods Lake, Carter Co., Missouri

Checking out a fen

Coonville Creek Natural Area, southeast Missouri (3 September 2015)

On yet another trip back to St. Louis from Tennessee, I made a spur-of-the-moment decision to visit Coonville Creek Natural Area in St. Francois State Park, an area I hadn’t seen in nearly 30 years and the outstanding feature being the calcareous wet meadow, or “fen”, that dominates the upper reaches of the creek drainage. Fen soils are constantly saturated, a result of groundwater from surrounding hills percolating through porous dolomite bedrock before hitting a resistant layer (in this case, sandstone) and seeping out onto the lower slopes. Constantly saturated soils and occasional fires (at least historically) have kept the fen open and treeless, with the cool groundwater allowing “glacial relicts” (i.e., plants common when glaciers covered the area) to persist.

Calcareous wet meadow | Coonville Creek, St. Francois State Park, St. Francois Co., Missouri

I saw a few Cicindela splendida (Splendid Tiger Beetles) on the rocky, clay 2-track leading to the area—a sure sign that fall was just around the corner, a female cicada on herbaceous vegetation in the fen (small, I think it’s not a species of Neotibicen), and a huge, fecund black and yellow garden spider (Argiope aurantia)—I love seeing the latter at this time of year when they have grown to their largest and the females are full of eggs. In reality, however, this visit turned into more of a botanical than an insect collecting experience. Insect activity in general was low, and my attention drifted instead to the diversity of wildflowers that were present on the fen—most new to me. False dragonhead (Physostegia virginiana), great blue lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica), and Spiranthes lacera (slender ladies’-tresses orchid)—its tiny white blossoms spiraling up the leafless spike were the most interesting, resulting in lots of time spent looking at them through the big camera.

Argiope aurantia | Coonville Creek, St. Francois Co., Missouri

The always exciting amorpha borer

Otter Slough Conservation Area, southeast Missouri (23 September 2015)

As the dog-days of summer gave way to bright, blue skies and crisp, fall air, a distinctive insect fauna takes advantage of the explosion of goldenrod that blooms across a landscape morphing from shades of green to orange, yellow, and tawny. Many of these insects are widespread and super-abundant—soldier beetles, tachinid flies, bumble and honey bees, and scoliid, tiphiid, and vespid wasps are among the most conspicuous. Megacyllene robiniae, longhorned beetles commonly called locust borers are also common on goldenrod during fall, but much less common is a closely related species that breeds in false indigo bush (Amorpha fruticosa)—Megacyllene decora, or the amorpha borer. I’ve seen this species several times, yet uncommonly enough that I still target it when I get the chance. One such place is Otter Slough Conservation Area—yet another interesting place along the way between Tennessee and St. Louis. On one of my final trips back this way I stopped by to see if these spectacular beetles would be out. My attention was first caught by egrets congregating in a mud flat exposed by recent dry weather. However, they were not what I was looking for.

Egrets congregating on mud flats | Otter Slough, Stoddard Co., Missouri

There is no shortage of interesting insects to look at as I begin scanning the goldenrod flowers growing along the roadsides and around the edges of the shallow pools managed for fishing and shore birds. A fat, female Stagmomantis carolina (Carolina mantis) sat on one of the first inflorescences that I checked, but she also was not what I was looking for.

Stagmomantis carolina | Otter Slough, Stoddard Co., Missouri

After a bit of searching, I found what I was looking for! Over the course of the next two hours (all the time I had left before sundown) I would a total of three adults on goldenrod flowers at three disparate locations within the area—again not very many, making those that I did see a real treat.

Megacyllene decora on goldenrod | Otter Slough, Stoddard Co., Missouri

As dusk fell over the area, insects began bedding down for the night. I was lucky to find the last amorpha borer in the dwindling light as it bedded down next to a bumblebee—perhaps the likely model for the beetle apparent mimetic coloration.

Megacyllene decora and a bumble bee bed down together | Otter Slough, Stoddard Co., Missouri

The sun sinking over the horizon behind the wetlands put an end to the collecting, not only for the day but for the season, at least here in Missouri and surrounding states. It would not be the final day of collecting for me, however, as I managed to scrape together some free time amidst my hectic travel schedule and spend a week in eastern Texas for the Annual Fall Tiger Beetle Hunt. I’ll save that trip for another report and close this one out here, but be on the lookout for higher quality photos over the coming months of the really interesting insects that I encountered over this past season. Let me also say that if you’re still reading at this point, you have my deepest admiration for having the persistence to wade through all 8,376 of the words contained within this post!

Sunset over Plover Pond | Otter Slough, Stoddard Co., Missouri

© Ted C. MacRae 2015

I believe this is another species of cactus dodger cicada (Cacama sp.).

I believe this is another species of cactus dodger cicada (Cacama sp.).