Nestled in the northern foothills of the St. Francois Mountains lies one of Missouri’s most remarkable of places—Hawn State Park. I have written about this place on several occasions and visited even more often, yet I never tire of exploring its sandstone canyons, rhyolite shut-ins, and stately pine forests. As such, I was happy to see it as the selected destination for the WGNSS Botany Group Monday Walk.

It was a chilly winter morning when the group met at the picnic area parking lot, and after a bit of discussion to orient ourselves on the plants we might see, we crossed the foot bridge over Pickle Creek to explore the habitats off the Whispering Pines Trail. Almost immediately (in fact, even before completely crossing the bridge), we noticed Alnus serrulata (smooth alder) lining the edges of the creek banks. Unlike many trees, A. serrulata is easy to recognize during winter by virtue of its persistent female cones and newly-formed male catkins. Alnus serrulata is one of five species in Missouri belonging to the family Betulaceae—all five of which occur together here in Hawn State Park (and, in fact, can be found within feet of each other). In the case of this species, the female cones are unique, the male catkins are green and red and occur during winter in clumps, and the winter buds are red with two scales.

Immediately after crossing the bridge, we saw the second betulaceous species on slightly higher ground—Corylus americana (American hazelnut). Like A. serrulata, this species is usually a small tree, but it lacks the persistent cones during winter, has more brownish male catkins that may be clumped, especially at the branch tips, but also tend to occur singly along the length of the branch, and has brownish, rounded winter buds and noticeably fuzzy twigs.

Entering the mixed pine-oak forest (and pondering Fr. Sullivan’s oak ID quiz—which turned out to be Quercus coccinea, or scarlet oak), Kathy noticed the persistent fruiting stalks of one of our native terrestrial orchids—Goodyera pubescens (downy rattlesnake plantain). Normally, this orchid is noticed during winter by virtue of its striking white-veined green leaves, but in this case they were completely hidden under leaf litter. Had it not been for the fruiting stalk, we would never have noticed its presence. Hawn State Park has a healthy population of these orchids, and hopefully the fruits of this individual will bear an abundance of its tiny (spore-sized) seeds.

Continuing our off-trail bushwhacking, we eventually reached a series of sandstone canyons that promised not only spectacular ice formations from their constant moisture drip, but the potential for seeing plants that rely on the cool, shaded, moist, acidic nooks and crannies they offer.

Two fern species were seen. The first was Asplenium platyneuron (ebony spleenwort)—not uncommon and distinguished by the dark, reddish-brown, glossy stipe and rachis (on fertile fronds) with simple pinnate leaves and alternately-arranged leaflets with a basal auricle (ear-lobe). Two columns of elongated sori (spore-bearing structures) oriented diagonally to the central veins can be found on their lower surface of the leaflets. Dryopteris marginalis (marginal wood fern) was also found on the sandstone ledges. This fern is most easily identified by the location of its sori on fertile fronds, which occur along the margins of its subleaflets (some other less common species will have the sori placed more interiorly).

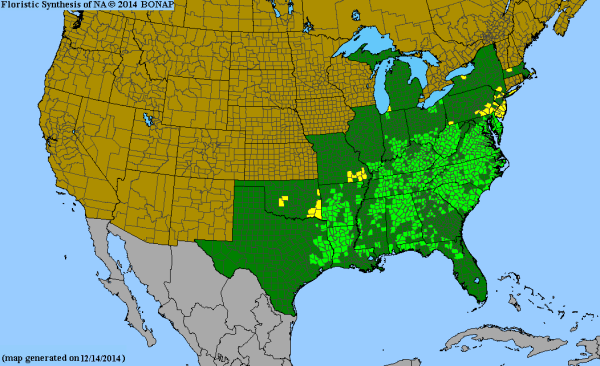

The most exciting find on the sandstone ledges was Mitchella repens (partridge berry). This member of the Rubiaceae (same family as coffee) is characteristic of sandstone canyons and ledges and occurs in Missouri only in a few counties in the southeastern part of the state where this habitat exists. The plant is unmistakable and easily identified, especially when in fruit. Interestingly, each of its bright red berries is actually a fusion of two fruits, as evidenced by the pair of minute, persistent calyces at the tip.

Back on-trail, the group focused on identifying the many different tree species along the trail (Quercus coccinea was dominant). One small “tree” had us stumped, however, it’s giant terminal bud with small lateral buds clustered nearby seemingly suggesting oak—until we noted the curious whorl at the branch node and, on a subsequently-seen individual, persistent fruit capsules that immediately identified it as Rhododendron prinophyllum (early azalea). Another lover of acidic pine woodlands, this species is restricted in Missouri to high-quality habitats in the Ozark Plateau, and Hawn State Park has some of the finest populations to be found.

As the group ascended the trail and began pondering whether to turn around, the characteristic leaves of a small saxifrage were seen at the base of an oak tree. Micranthes virginiensis (early saxifrage, Virginia saxifrage) shows a preference for rocky acid soils and reaches the western limit of its distribution in Missouri, where it is limited to a few counties in the Ozarks. A similar but much smaller species, Micranthes texana (Texas saxifrage) can be found in sandstone glades in western Missouri.

Returning to Pickle Creek, the group focused on the remaining three species of Betulaceae found in Missouri—and Hawn State Park, all growing in the immediate vicinity of the foot bridge. The three species—Betula nigra (river birch), Carpinus caroliniana (American hornbeam, musclewood, blue beech), and Ostrya virginiana (American hophornbeam), all have numerous subtle characters that distinguish them from the other two members of the family (Alnus and Corylus), but in winter they are most easily recognized by their bark. The flaky, peeling, cinnamon-brown bark of B. nigra is the most distinctive and cannot be mistaken for anything else. This contrasts completely with the smooth, gray, sinuous look of C. caroliniana (which I can’t help but stroke whenever I see it—should I be admitting that!?). In between is the rough, shredded, brownish appearance of O. virginiana (which is further distinguished from C. americana by its pointed rather than rounded buds).

©️ Ted C. MacRae 2022