…is in other people’s collections!

I’ve been working hard the past couple of weeks on one of three batches of Buprestidae in the insect collection at the Illinois Natural History Survey sent to me for identification. I’ve already completed one of these batches, which included all specimens strictly from Illinois. This second batch includes specimens from the not only the rest of North America (sensu lato), but South America and the West Indies as well. Out of ~450 total specimens, in this batch, I identified 167 species, with eight new state and two new country records.

Why do I do it? While I’d like to say it’s because I’m just a nice guy, and I do genuinely enjoy helping to improve the level to which public insect collections are curated, my motives aren’t completely unselfish. First, it is a chance for me to glean the specimens for new data in the form of unknown distributional and host plant records. This is a main area of interest for me, and the data provide fuel for my publications on the subject. Second, and perhaps, it is a chance to encounter species that are absent or poorly represented in my cabinets. Most public collections allow specialists to retain a certain number of duplicates of the species they identify. This allows me to increase the representation of species in my collection, which in turn increases its usefulness as a resource for even further identifications. (In this particular case, the INHS collection manager graciously allowed me even to retain a handful of singletons in exchange for some other species that helped to improved the representation in their collection.) Finally (and perhaps most importantly), regularly examining new material helps to continually refine my understanding of species concepts. Sometimes this causes me to reassess a previous identification in light of an improved understanding (a reference collection is only useful if its representatives are correctly identified).

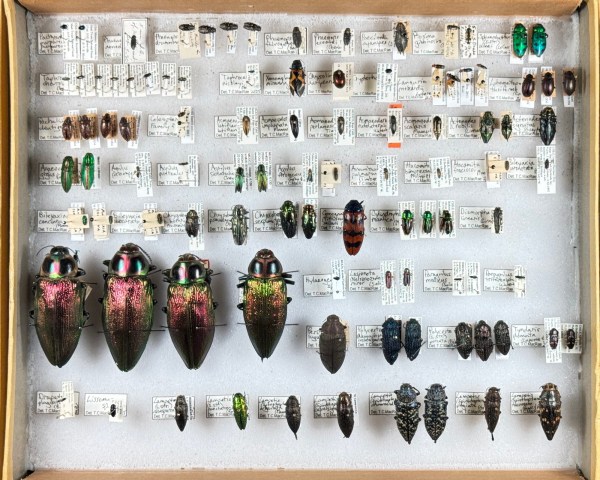

For those wondering, here is what 165 species of Buprestidae looks like:

©️ Ted C. MacRae 2025

Your rationale for doing this work makes great sense! How large are those big beetles in the third case and where do they live? Curious. I’m not sure I have ever seen a beetle so large. Sher

Hi Sher – the biggest of the three measures 65 mm (2.6 in) in length – it is Euchroma giganteum from South America and the West Indies, and it is thelargest jewel beetle in the world. The specimen to its left is a slightly smaller individual of the same species, while the one to its right is Euchroma goliath, a close relative that occurs in Mexico, Central America, and northern South America.

Thanks for this information. Beetles this size would be very noticed by humans, and this makes me wonder the role jewel beetles might play in folklore. I mean did the beetles make it into cultural stories. And I wonder in tribal societies if beetles were ever eaten. These ponderings fall into humanities and anthropology I guess … just musing. Thanks again for your reply.

Yes, these beetles featured prominently in indigenous cultures. The larvae (extraordinarily large grubs found in dead wood) were consumed as food, and the adult elytra (wing covers) were used for ornamentation. Some other, mostly very large, beetle species had similar uses throughout Central and South America.