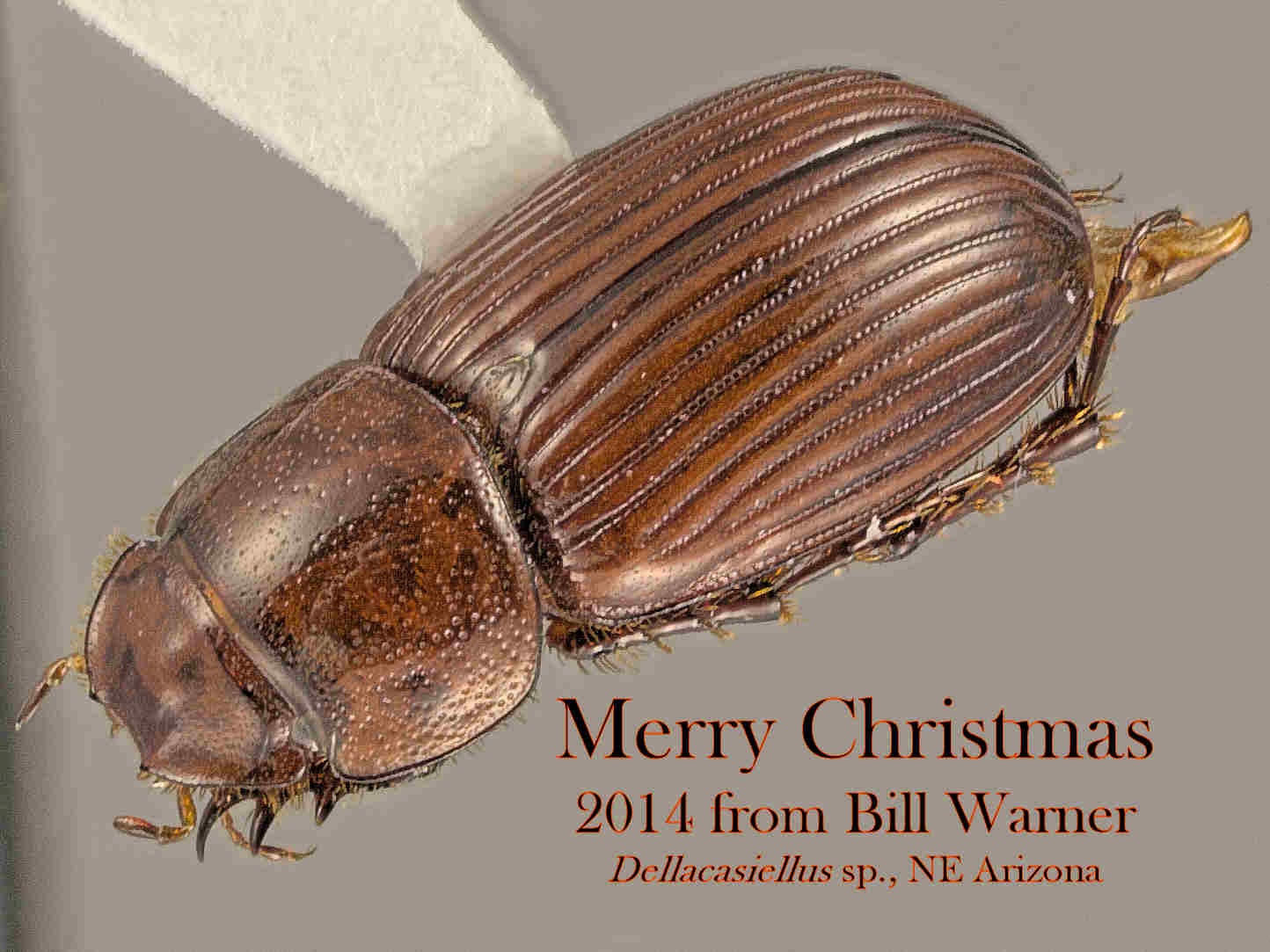

[Note: this is the 1,000th post on Beetles in the Bush!]

Here is one of the gifts that I received for Christmas last month, a vintage copy of Gulliver in the Bush — Adventures of an Australian Entomologist, published in 1933 by H. J. Carter.

You may have already noticed the striking similarity of the title of this book to the name of this blog (Beetles in the Bush — Experiences and Reflections of a Missouri Entomologist) and its themes (tales of entomological exploits in our native lands). You would also be forgiven if you assumed that I named my blog after this book. In reality, the similarity of names is purely coincidental—I’d never heard of this book when I started writing this blog back in 2008, and in fact it was just this past year (while writing a review of the newly published Jewel Beetles of Australia—look for my review of this very nice book to be published in the next issue of The Coleopterists Bulletin) that I even became aware of the book’s existence. Once I did, however, I had to have it, and I love my wife for finding a copy of it and giving it to me for Christmas.

I’m looking forward to reading through the books nearly century-old pages and reading of Carter’s exploits in what surely must have been a much wilder and unspoiled world than the one I have been able to explore. Nevertheless, I am sure I will also find many similarities in our experiences—-observing the fascinating bounty nature up close and personal, discovering new species (whether just to me or to science as a whole), and reveling in the “thrill of the hunt.” Beyond enjoying the book itself, however, the eerie similarity of book/blog titles and themes only further convinces me of something that have been considering for a while—that I should condense and the writings on my blog and assemble them into a book of my own, one titled after this blog and detailing the experiences of an entomologist one century after and half a world removed from Carter. Perhaps, if I do this, some future entomologist will receive an old copy of my book as a gift in the 22nd century!

©️ Ted C. MacRae 2025

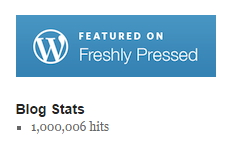

I knew it was coming, and yesterday it happened. I was really hoping to see hit number 1,000,000 appear on the small ‘Blog Stats’ item at the bottom of the right sidebar, but I just missed it due to a small traffic spike right around the time that it occurred. As near as I can tell, the one millionth hit came at 1:27 p.m. (Central Standard Time) from somebody in Tempe, Arizona. Whoever you were, whether a regular reader or just passing by, congratulations. However, the real thanks must be shared with all of you who helped log the previous 999,999 hits, for without you there would be no Beetles in the Bush. Here’s to two million!

I knew it was coming, and yesterday it happened. I was really hoping to see hit number 1,000,000 appear on the small ‘Blog Stats’ item at the bottom of the right sidebar, but I just missed it due to a small traffic spike right around the time that it occurred. As near as I can tell, the one millionth hit came at 1:27 p.m. (Central Standard Time) from somebody in Tempe, Arizona. Whoever you were, whether a regular reader or just passing by, congratulations. However, the real thanks must be shared with all of you who helped log the previous 999,999 hits, for without you there would be no Beetles in the Bush. Here’s to two million!