6 Oct 2025—Fall continues to advance in the St. Louis area, and despite very dry conditions during the past two months the fall bloomers continue to make their appearance. One of the area’s most reliable and interesting places to see fall blooms is Victoria Glades south of Hillsboro, where orchids, gentians, and asters anchor a unique suite of fall-blooming plants that are rarely seen elsewhere in our mostly forested environs.

The group chose the Nature Conservancy portion of the complex to explore, as it was in the mesic forest along the riparian corridor below the glade on this side that the first of two orchids—the charmingly diminutive and seldom-seen Spiranthes ovalis (lesser ladies’ tresses)—was expected to be seen in bloom. Despite having recently taken GPS coordinates for the plants, it took several minutes of the group scouring the area around the coordinates before the tiny plants were finally found. Its delicate blooms, fall flowering season, small size, presence of basal and cauline leaves at anthesis, and preference for mesic habitats all serve to identify this species. Missouri’s populations are considered var. erostella, which lack certain essential flowering organs and are, thus, self-pollinated (cleistogamous).

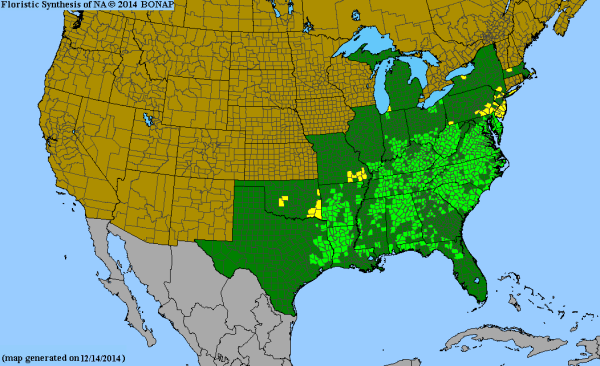

Clambering up and out of the creek bed and onto the open glade, the group found, again with some difficulty, the second orchid we were looking for—Spiranthes magnicamporum (Great Plains ladies’ tresses). Unlike S. ovalis, however, this species is much more commonly seen on dolomitic glades throughout the state, and there have been fall seasons at Victoria Glades featuring spectacular displays of it. Sadly, it does not appear that this will be one of those falls, almost surely because of the near absence of rain in recent months. The first two plants were found under and next to a cut eastern red-cedar, whose cadaver perhaps provided just enough protection to prevent a complete drying of the soil underneath and allowed the two plants to proceed to flowering. Of the nine species of Spiranthes presently known to occur in Missouri, S. magnicamporum is among the showiest due to its robust, often doubly helical inflorescences and relatively large flowers with spreading and arching lateral sepals. It is also among the most fragrant, with a sweetish fragrance of coumarin, which some people liken to vanilla.

I’ve been visiting Victoria Glades for more than 40 years, yet I continue to see things I haven’t previously notified. This time it was Trichostema coeruleum (pennyroyal bluecurls), a member of the mint family (Lamiaceae). [Note: Trichostema coeruleum was known until recently as Trichostema brachiatum—now a synonym of Trichostema dichotomum.] Unlike Trichostema dichotomum (bluecurls), which prefers glades and other dry habitats with acidic substrates (e.g., sandstone), T. coeruleum prefers such habitats with calcareous substrates (e.g., dolomite). A third species of the genus, Trichostema setaceum (narrow-leaf bluecurls), also occurs in Missouri but is restricted to sand prairies in extreme southeastern Missouri.

Dolomite glades are also the preferred habitat for many species of plants in the family Orobanchaceae, a bizarre family of mostly hemiparasitic plants that derive at least some of their nutrition not from the sun, but by tapping into the roots of nearby plants. Castilleja coccinea (scarlet paintbrush) is perhaps the best known of these, in most years joining the cacophony of wildflowers that form colorful displays across Victoria Glades during spring and early summer. There are, however, several less conspicuous but equally beautiful wildflowers in the family that are restricted in the area almost exclusively to the dolomite glades of Jefferson Co. One of these is Agalinis skinneriana (Skinner’s or pale gerardia/false foxglove), which the group found sporadically still in bloom across the open glade. There are several species of Agalinis in Missouri, some of which are quite common. However, A. skinneriana can usually be recognized by the characteristic habitat and generally upward-facing flowers with spreading to reflexed upper corolla lobes. The plants are also relatively slender and fewer-branched than the more common A. tenuifolia (common gerardia/false foxglove) and A. gattingeri (rough-stemmed gerardia/false foxglove).

Another plant in the family Orobanchaceae that the group saw was Buchnera americana (American bluehearts), represented by a single plant still bearing two worn blossoms. Normally blooming from June through September, plants in full bloom have no look-alikes and are not likely to be confused with anything else. Despite this, the vervain-like fruit-bearing structure of this late straggler fooled the group into at first thinking it was a species of Verbena until its true identity was realized.

No group of plants more iconically represents fall than goldenrods (genus Solidago) and true asters (genus Symphyotrichum), and no place allows as many uncommonly seen species to be seen together as the dolomite glades. Three species of goldenrods were seen during the day—the super common Solidago nemoralis (old field goldenrod), the less common but more showy Solidago rigida (stiff goldenrod), and the highly restricted Solidago gattingeri (Gattinger’s goldenrod) (we were not able to locate a fourth species—Solidago radula [rough goldenrod], which we have observed during previous visits on the MDC portion of Victoria Glades). It was the true asters, however, that truly tested our plant identification abilities. Relatively easier are the purple asters, of which we found three species. The first and most abundant was Symphyotrichum oblongifolium (aromatic aster), recognized by its recurved phyllaries and branched habit with narrow, linear leaves that become more numerous and smaller in the upper plant. If one is still in doubt as to its identity, however, one needs only to crush the leaves between the fingers and enjoy its distinct aroma.

Along the intermittent creek and near the interface with the dry post oak woodland on the north of the glade, we encountered a second species—Symphyotrichum oolentangiense (azure aster). Identification of this species came only near the end of the outing, as a key identifying characteristic of this species—the presence of distinctly petiolate cordate basal leaves that are rough to the touch—was not seen on any of the plants examined before then. At that point, we suspected Symphyotrichum turbinellum (prairie aster) due to the vase-shaped involucres. While that species has been found at Victoria Glades, it is usually a much more highly branched plant associated with more wooded habitats (despite the common name). Finally, we found a plant with such leaves present, albeit dried up, and then another with the leaves present and still fresh to confirm the identification.

In a small area at the northernmost point of the glade, we found Symphyotrichum sericeum (silky aster). This species is immediately recognizable from afar by the silvery cast to the foliage—this, combined with its highly preferred habitat of glades or dry prairies are usually enough to identify the species, although it is said that the flowers are often more purple and less bluish than other “purple asters.”

As we walked the margins of the glade, the group kept their collective eyes out for Gentiana puberulenta (downy gentian), a striking and rarely seen fall flowering species that has been found on several occasions at Victoria Glades. The species has been seen at Victoria Glades on a few occasions in past years, and the locations of these sightings were scoured thoroughly but without success. Unexpectedly, near the end of the outing, a single plant in flower was located—its perfectly fresh blossom initially hidden from view underneath fallen leaves. One of three members of the genus Gentiana in Missouri, this species is easily differentiated by having the corolla spread open at maturity. Missouriplants.com notes “The rich, deep blue color of the corollas is a striking and uncommon hue among our flora.” A strikingly beautiful final find of the day indeed, and a perfect note on which to gather for lunch at historic Russell House in nearby Hillsboro.

For me, no botany outing is strictly about plants (just as no entomology outing is strictly about insects), so there were a few interesting insect observations on the day. On our way to look for Spiranthes ovalis (lesser ladies’ tresses), June noticed a caterpillar on the Ulmus rubra (slippery elm) that we decided must represent Halysidotus tessellaris banded tussock moth).

Later, after lunch with the group, I returned with the goal of more closely inspecting Physocarpus intermedius (Midwest ninebark) along the glade toeslopes and intermittent creek to see if Dicerca pugionata was out. It has been many years since I’ve seen this species in the fall (but it has also been many years since I’ve really tried to look for it during the fall). I started first with the plants along the moist toeslopes along the west side of the glade, checking several of the now very scraggly-looking plants without success. Along the way, I encountered an especially beautiful Spiranthes magnicamporum, so I paused to take photos. While doing so, I noticed a cryptically-colored crab spider on its blossoms—Mecaphesa asperata (northern crab spider)—the first time I’ve ever seen a spider hunting on the flowers of an orchid.

Towards the end of the toeslopes, finally, two D. pugionata plopped onto my sheet. The plant they were on was near the far end of the toeslopes, and if I hadn’t seen any beetles by the time I reached the far end I would have given up the search. Finding them, however, motivated me to hike over to and continue looking along the intermittent creek, where I saw three more beetles in three different spots, the last one—satisfyingly—on the very last plant I checked before the creek disappears into denser woodland.

Mission accomplished, I enjoyed one more leisurely stroll across the glade before calling it another (successful) day in the field.

©️ Ted C. MacRae 2025