![]() “No feces for this species.” “Carnivorous dung beetle shuns dung and decapitates millipede.” “Little dung beetle is big chopper.” “Dung beetle mistakes millipede for dung.” These were some of the clever headlines that I had to compete with in coming up with my own opener for a remarkable beetle that titillated the science blogosphere last week. At the risk of being redundant, I’d like to revisit that beetle and offer a few (hopefully novel) thoughts of my own. I can say that I have a unique and special treat for those willing to read further.

“No feces for this species.” “Carnivorous dung beetle shuns dung and decapitates millipede.” “Little dung beetle is big chopper.” “Dung beetle mistakes millipede for dung.” These were some of the clever headlines that I had to compete with in coming up with my own opener for a remarkable beetle that titillated the science blogosphere last week. At the risk of being redundant, I’d like to revisit that beetle and offer a few (hopefully novel) thoughts of my own. I can say that I have a unique and special treat for those willing to read further.

First the background. Deltochilum valgum is a so-called “dung beetle” in the family Scarabaeidae that lives in the lowland rain forests of Peru. As suggested by its common name, it belongs to a group of beetles that are well known for their dung feeding habits. Over 5,000 species of dung beetles are known throughout the world, all of which carve out balls of dung and bury them as provisions for larval development – or so it was thought. As reported by Trond Larsen of Princeton University and colleagues in Biology Letters, D. valgum has apparently abandoned its ancestral dung ball-rolling behavior in favor of a predatory lifestyle. Its prey – millipedes! Moreover, the species exhibits several distinct morphological traits that appear to have evolved as a direct result of their predatory behavior. Adult beetles were repeatedly observed killing and eating millipedes, and their disdain for dung was rather conclusively demonstrated by an exhaustive, year-long trapping program in which pit-traps were baited with a variety of bait types known to attract dung beetles (e.g., various kinds of dung, carrion, fungus and fruit) – and millipedes. In all, over 100,000 dung beetles representing 132 species were trapped (what a nice collection!), 35 of which were found to scavenge on dead millipedes, but only five of these dared tackle live millipedes. Of these, only D. valgum ignored all other foods – it only came to traps baited with live millipedes.

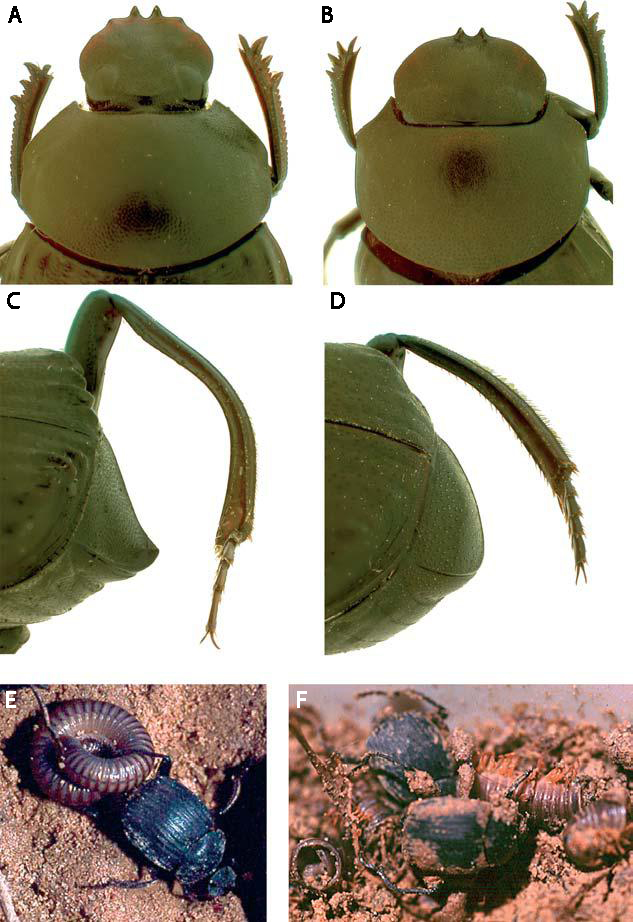

Larsen et al. determined that adults of D. valgum are opportunistic hunters and were much more likely to attack injured millipedes than healthy ones, even those weighing 14 times as much as the beetle. Ball rolling behavior was never observed by D. valgum. Most dung beetles have wide, shovel-shaped heads used to scoop and mold dung balls, but D. valgum has a much narrower head with sharp “teeth” on its clypeus (Fig. 1A vs. 1B). The teeth apparently aid in killing the millipede by piercing the ventral surface behind the head and prying upwards (decapitating it), and the narrow, elongate head facilitates insertion into the millipede body for feeding. Further, the hind tibia are elongate and curved, which are used to “grip” millipedes by holding them up against the dorsally reflexed pygidium (Fig. 1C vs. 1D). This allows the beetle to drag its coiled up victim with one hind leg while walking forward on the other five (Fig. 1E). Once killed, the beetles proceeded to break their prey into pieces and consume their meaty innards, leaving the disarticulated millipede exoskeletons licked clean (Fig. 1F). One of these “attack” episodes was filmed (using infrared lighting so as not to affect their nocturnal behavior) and can be seen in this BBC News video.

Figure 1. (a) Dorsal view of D. valgum head. Sharp clypeal teeth and angled clypeus act as a lever to disarticulate millipede. Narrow, elongate head permits feeding inside millipede; (b) dorsal view of Deltochilum peruanum head, lacking characters described in (a), head used to mould dung balls; (c) lateral view of D. valgum pygidium and hind tibia. Dorsally reflexed pygidial lip is used to support millipede during transport. Elongate, strongly curved hind tibia is used to grip millipede. (d ) Lateral view of D. peruanum pygidium and hind tibia, lacking characters described in (c), hind tibia used for rolling dung balls. (e, f ). Predation strategy by D. valgum. (e) Dragging live, coiled millipede with one hind leg, walking forwards; ( f ) feeding on killed millipede with head inside

segments; disarticulated empty millipede pieces nearby.

Credit: Larsen et al. (2009).

Much has been made about this remarkable shift from coprophagy to predation, which Larsen et al. speculate was driven by competition for limited resources with the many other dung beetle species that occur in the Peruvian rainforests. In fact, adult dung beetles are known to feed on a variety of resources besides dung, as exemplified by the range of baits used in their survey. Thus, my first thought after reading the coverage was actually a question: “Has this species abandoned dung provisioning completely as a reproductive strategy?” Everything I had read focused exclusively (quite understandably) on the bizarre feeding habits of the adults, but there was no mention of what the species’ larval provisioning strategies were. Wanting more information about this, I contacted Trond Larsen, who graciously sent me a PDF of the paper. Unfortunately (though not a criticism of the paper), no further insight about this was found in the paper either. Indeed, in all of the observations recorded by Larsen et al., millipedes killed by D. valgum were consumed entirely by the adults, and no mention was made of how or whether millipedes were utilized for larval provisioning. I wondered if D. valgum had truly abandoned dung provisioning for larval development (a remarkable adaptive switch), or if in fact the species might still utilize the strategy for reproduction (perhaps having specialized on a dung type not included in their survey), while also exploiting millipede predation as adults for a nutritional advantage. I asked Trond about this, to which he replied with this juicy tidbit (I told you I had a special treat!):

Yes, I would very much like to know what the reproductive/nesting behavior of D. valgum is. My best guess is that they also use millipedes as a larval food source, but as you say, we haven’t observed that behavior yet. I have observed other generalist dung beetle species rolling balls out of dead millipedes, presumably to bury for the larvae, so I certainly think it would be an adequate food source. Many dung beetle species use carrion for their larvae.

I am quite confident that D. valgum does not use any kind of dung. I have sampled these dung beetle communities very thoroughly, with many dung types and other bait types, and also with passive flight intercept traps that catch all beetles. Every dung beetle species that feeds on dung is at least sometimes attracted to human dung (this is not the case in African savannahs though, but is in neotropical forests – that is a whole different story). There are still a small handful of species we catch in flight intercept traps that we don’t know what they eat, although some of these mysteries have recently been solved – many of them live in leaf-cutter ant nests for example.

While predation of millipedes by a dung beetle is itself a fascinating observation, demonstrating the abandonment of dung provisioning in favor of captured prey for larval development would be a truly remarkable example of an ecological transition to exploit a dramatically atypical niche. I hope Trond (or anybody for that matter) actually succeeds in observing millipede/prey utilization for larval provisioning by this species.

Many thanks to Trond Larsen for his delightful correspondence.

SOURCE:

Larsen, T. H., A. Lopera, A. Forsyth and F. Génier. 2009. From coprophagy to predation: a dung beetle that kills millipedes. Biology Letters DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2008.0654.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2009