The Florida scrub lizard (Sceloporus woodi) is restricted to isolated sand scrub habitats in peninsular Florida.

Tiger beetles were not the only rare endemic species that I encountered during my visit to the Lake Wales Ridge in central Florida last August. I didn’t know what this small lizard was as I watched it bolt from the trail and scamper for cover during my approach; however, having already found two endemic tiger beetles, I had a feeling that this lizard might also be a good one. The photo shown here is admittedly not one of my best, but it was the only one I managed to get before the lizard ducked into the brush for good. Horribly overexposed, I did what I could with it in Photoshop to make it halfway presentable, but there is no question that its subject represents a Florida scrub lizard, Sceloporus woodi¹. This small, diurnal, ground-dwelling lizard belongs to the family Phrynosomatidae (same family as the Texas horned lizard that I featured in this post) and is restricted to Florida’s rare sand scrub and sandhill habitats. Like the recently featured Highlands Tiger Beetle, this species is threatened by the isolated, disjunct nature of its required habitat—a threat made worse by the ever increasing pressures of agricultural conversion and urban development.

¹ Sceloporus is derived from the Greek word scelos meaning “leg” and the Latin word porus meaning “hole”, referring to the pronounced femoral pores found in this genus of lizards. The species epithet honors Nelson R. Wood, a taxidermist at the U.S. National Museum who collected the type specimen in 1912.

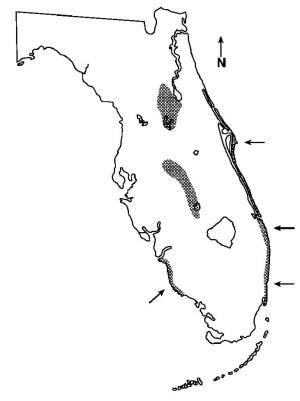

The Florida scrub lizard is related to and closely resembles the much more common and widely distributed southern fence lizard (Sceloporus undatus), which co-occurs with the scrub lizard in northern Florida. Fence lizards, however, lack the dark brown lateral stripe that is clearly visible in the above photo, a feature seen in juveniles and adults of both sexes of the scrub lizard. Juvenile and adult female scrub lizards also exhibit a dorsal zigzag pattern; however, this fades in males as they reach adulthood and develop the characteristic bright blue belly patches that are seen in both this species and in the fence lizard (Branch and Hokit 2000). Since light blue patches are just visible on the belly and throat of the individual in the photograph, I haven’t been able to determine whether it represents a mature female or a still-juvenile male—any help from a knowledgeable reader would be greatly appreciated. Unlike the fence lizard, the scrub lizard displays a high degree of habitat specificity, occurring as disjunct populations in strict association with the major sand scrub ridges of Florida. The healthiest populations are found on the Mt. Dora Ridge in northern peninsular Florida, on which significant remnants of scrub habitat are preserved in the Ocala National Forest. Populations also occur on the Lake Wales Ridge of central Florida and the Atlantic Coastal Ridge, but the status of these populations is less secure. Populations also once occurred along the southwestern coast on the Gulf Coast Ridge, but these populations are now believed extirpated as a result of urban development (Jackson 1973, Enge et al. 1986). While the Florida scrub lizard is not listed as a threatened or endangered species at the state or federal level, its high specificity to an increasingly isolated and fragmented habitat and its apparently low dispersal capabilities are clear causes for concern over its long-term prospects. As remnant habitats continue to shrink and become more isolated, the threat of localized extinction becomes an increasing concern for the lizard populations that they support.

The precarious status of scrub lizards and their occurrence in several disjunct, isolated populations makes them interesting subjects for genetic studies. Mitochondrial DNA analyses suggest that scrub lizard populations exhibit a high degree of phylogeographical structure, with populations diverging significantly not only between major scrub ridges, but also within them (Branch et al. 2003). The findings support the notion of long-term isolation of scrub lizard populations on the major scrub ridges and confirm their low dispersal rates among adjacent scrub habitats within ridges (as little as a few hundred yards of “hostile” habitat may be sufficient to prevent movement to adjacent habitats). More significantly, the results support the concept of two distinct morphotypes on the Mt. Dora and Lake Wales Ridges and also raise the possibility that Atlantic Coastal Ridge populations represent a distinct evolutionary entity as well. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that scrub lizards evolved in central Florida, where they were isolated when surrounding lands were inundated by rising sea levels during the late Pliocene and subsequent interglacial periods during the Pleistocene. During periods of low sea level they dispersed to the younger Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Ridges, where they were isolated from parent populations when more mesic conditions returned during the Holocene (12 kya to present). The genetic distinctiveness of these different ridge populations may justify qualifying each of them for protection as “significant evolutionary units” under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, since it raises concerns about the use of translocations, a common strategy for establishing new populations in restored habitat or augmenting existing populations, as a conservation strategy for the species as a whole. Since lizards located on different ridges are more divergent than lizards from populations located on the same ridge, movement of lizards between ridges could compromise the integrity of the genetic differences that have accumulated over millions of years and result in loss of genetic diversity. As a result, augmenting populations on the Lake Wales and Atlantic Coast Ridges with lizards from robust populations on the Mt. Dora Ridge may not be desirable. Instead, it may be necessary to protect individual scrub lizard populations on each of the major scrub ridges in order to preserve as much of their genetic diversity as possible.

REFERENCES:

Branch, L. C. and D. G. Hokit. 2000. Florida scrub lizard (Sceloporus woodi). University of Florida, IFAS Extension Service Publication #WEC 139, 3 pp.

Branch, L. C., A.-M. Clark, P. E. Moler and B. W. Bowen. 2003. Fragmented landscapes, habitat specificity, and conservation genetics of three lizards in Florida scrub. Conservation Genetics 4:199

Enge, K. M., M. M. Bentzien, and H. F. Percival. 1986. Florida scrub lizard status survey. Technical Report No. 26, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Jacksonville, Florida, U.S.A.

Jackson, J. F. 1973. Distribution and population phenetics of the Florida scrub lizard, Sceloporus woodi. Copeia 1973:746–761.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2009