Florida is known for its rich assemblage of tiger beetles—27 species in all, including four endemics (Choate 2003). However, late summer is generally considered not the best time of year for seeing this diversity, since adult populations of most species begin to wane as the intensity of the summer heat reaches its peak. I knew the timing of my family vacation in early August might be a bit off; however, considering I had never looked for tiger beetles in Florida before, I remained optimistic that I still might encounter some interesting species. My optimism was quickly rewarded—in one afternoon of exploring the small coastal preserve just outside the back door of my sister-in-law’s condo, I found Ellipsoptera marginata (Margined Tiger Beetle), its sibling species E. hamata lacerata (Gulf Beach Tiger Beetle), and several 3rd-instar larvae in their burrows that proved to be the Florida endemic Tetracha floridana (Florida Metallic Tiger Beetle). Good fortune would continue when I made a one-day trip to the interior highlands in a successful bid to find Florida’s rarest endemic, Cicindela highlandensis (Highlands Tiger Beetle), finding also as a bonus the splendidly camouflaged and also endemic Ellipsoptera hirtilabris (Moustached Tiger Beetle). Five species, including three endemics, in just over a day of searching! I had one more day to sneak off and do what I love most, and I wanted to make the most of it.

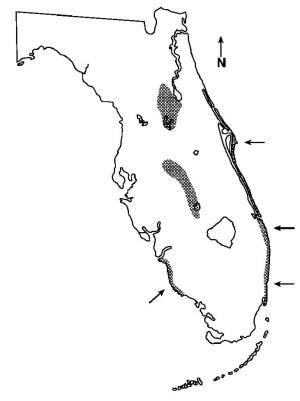

Among the suggestions given to me by my colleagues, the most promising-sounding was the “end of the road,” a Gulf Coast salt marsh near Steinhatchee in Dixie County where I was told as many as 6-10 species of tiger beetles could be seen at once. I didn’t know it at the time, but this particular location has achieved legendary status among tiger beetle enthusiasts (Doug Taron recently wrote about his experience, calling it the Road to Nowhere). A 200+ mile drive from my base near St. Petersburg, it would take the better part of 5 hours to drive there, and not wanting to put all of my eggs in one basket, I looked for potential stops along the way. About midway along the drive was Withlacoochee State Forest, where one of my colleagues had told me I might still find the fairly widespread Cicindela abdominalis (Eastern Pinebarrens Tiger Beetle) and its close relative, C. scabrosa (Scabrous Tiger Beetle)—the fourth Florida endemic. My plan was to leave early in the morning and spend a few hours at Withlacoochee before driving the rest of the way to finish out the day at Steinhatchee.

It took some time to find my bearings upon arriving, but after some discussion with the decidedly forestry-oriented staff at the headquarters, it seemed that the Citrus Tract was where I wanted to be. I was looking for the sand barren and pine sandhill habitats that these species require, and the staff’s description of the northern edge of the tract as having lots of sand and “not very good for growing trees” suggested this might be the place. Pine sandhill (also called “high pine”) is a pyrophytic (fire-dependent) plant community characterized by sandy, well-drained soils, a widely-spaced longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) and turkey oak (Quercus laevis) canopy, and an herbaceous layer dominated by wiregrass (Aristida stricta). I quickly found such habitat in the area suggested, and it wasn’t long before I found the first of the two species—C. abdominalis—rather commonly along a sandy 2-track leading through the area. For those of you who see a distinct resemblance of this species to the rare C. highlandensis that I highlighted from my trip to the central highlands, this is no coincidence. Cicindela abdominalis is very closely related to that species, the latter distinquished by an absence of flattened, white setae on the sides of the prothorax and the abdomen and by the highly reduced or absent elytral maculations (Choate 1984). Dense white setae and distinct apical elytral maculations are clearly visible in the individuals shown in these photographs.

It was a blistering hot day (just as every other day on the trip had been so far), and it wasn’t only me who felt that way. Tiger beetles, of course, are ectothermic and rely upon their environment for their body temperature. Despite this, they are able to regulate body temperatures to some degree by using a range of behavioral adaptations intended to mitigate the effects of high surface temperatures and intense sunlight. The photos above show one of these behaviors, known as stilting. In this behavior, the adult stands tall on its long legs to elevate its body above the thin layer of hotter air right next to the soil surface and as far off the sand as possible (Pearson et al. 2006). As the heat of the day intensifies and the zone of hot air at the soil surface broadens, stilting alone may be insufficient to prevent overheating. When this happens, the beetles combine stilting with sun-facing, a behavior in which the front part of the body is elevated with the head oriented towards the sun. This position exposes only the front of the head to the sun’s direct rays, thus minimizing the body surface area exposed to incident radiation.

I was also fortunate to have another chance at photographing the beautiful and marvelously-camouflaged Ellipsoptera hirtilabris (Moustached Tiger Beetle), which, in similar fashion to C. highlandensis, I found co-occurring with C. abdominalis in rather low numbers. As before, they were extremely wary and difficult to approach, especially in the extreme heat of the day, and all of my best efforts to get a good shot of the species in its “classic” pose were frustrated. The photo above was about as close as I could get to any of these beetles when they were out in the open before they would flee; however, it nicely demonstrates the use of stilting combined with sun-facing during the hottest part of the day.

Another behavioral response to extreme heat is shade-seeking—adults may either remain active, shuttling in and out of shaded areas, or avoid exposed areas altogether and become inactive. One thermoregulatory behavior for extreme heat that I did not observe was daytime-burrowing, in which adults construct temporary shallow burrows during the hottest hours of the day. Although I did not observe this behavior by either species at Withlacoochee, I have seen it commonly among several species in sandy habitats here in Missouri and in the Sandhills of Nebraska (e.g., Cicindela formosa, Cicindela limbata, Cicindela repanda, Cicindela scutellaris, Cicindela tranquebarica, Ellipsoptera lepida).

There was one disappointment on the day—I did not see C. scabrosa. However, I still had the “end of the road” to explore, so I remained happy with the now six species I had encountered and optimistic about finding additional species later in the day…

Photo Details: Canon EOS 50D, ISO 100.

Habitat: Canon 17-85mm zoom lens (landscape, 17mm), 1/100 sec, f/10, natural light.

Insects: Canon 100mm macro lens (manual), 1/250 sec, f/16–18 (C. abdominalis) or f/20–22 (E. hirtilabris), MT-24EX flash w/ Sto-Fen diffusers.

REFERENCES:

Choate, P. M., Jr. 1984. A new species of Cicindela Linnaeus (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) from Florida, and elevation of C. abdominalis scabrosa Shaupp to species level. Entomological News 95:73–82.

Choate, P. M., Jr. 2003. A Field Guide and Identification Manual for Florida and Eastern U.S. Tiger Beetles. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 224 pp.

Pearson, D. L., C. B. Knisley and C. J. Kazilek. 2006. A Field Guide to the Tiger Beetles of the United States and Canada. Oxford University Press, New York, 227 pp.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2009