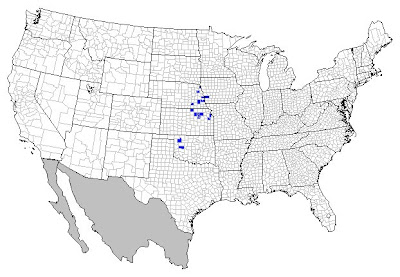

One of the more enigmatic tiger beetle species in North America is Cicindela celeripes LeConte (swift tiger beetle). This small (6-8 mm), flightless species has been recorded from a restricted area of the eastern and southern Great Plains – from eastern Nebraska and westernmost Iowa south through Kansas to western Oklahoma and the Texas panhandle (Hoback and Riggins 2001, Pearson et al. 2006).  Unfortunately, populations of this species appear to have suffered severe declines. It apparently is holding strong in the Flint Hills region of Kansas, but many of the records from outside of that area date back more than a century. Reportedly once common on the bluff prairies along the Missouri River, it has not been seen in Nebraska since 1915 and may have been extirpated from that state (Brust et al. 2005). The reasons for this decline undoubtedly involve loss of preferred habitat – upland prairies and grasslands with clay or loess soils and sparse or patchy vegetation. Areas supporting these native habitats have been drastically reduced since European settlement of the region, and suppression of fire – so vital to prairie ecosystems – has led to extensive woody encroachment on the few prairie relicts that do remain. Unlike many other tiger beetle species that have been able to adapt to these anthropogenic changes, this species apparently cannot survive in such altered habitats.

Unfortunately, populations of this species appear to have suffered severe declines. It apparently is holding strong in the Flint Hills region of Kansas, but many of the records from outside of that area date back more than a century. Reportedly once common on the bluff prairies along the Missouri River, it has not been seen in Nebraska since 1915 and may have been extirpated from that state (Brust et al. 2005). The reasons for this decline undoubtedly involve loss of preferred habitat – upland prairies and grasslands with clay or loess soils and sparse or patchy vegetation. Areas supporting these native habitats have been drastically reduced since European settlement of the region, and suppression of fire – so vital to prairie ecosystems – has led to extensive woody encroachment on the few prairie relicts that do remain. Unlike many other tiger beetle species that have been able to adapt to these anthropogenic changes, this species apparently cannot survive in such altered habitats.

Chris Brown and I have been interested in this species ever since we began surveying the tiger beetles of Missouri. It has not yet been recorded from the state, but we have long suspected that it might occur in extreme northwest Missouri. It is here where the Loess Hill prairies along the Missouri River reach their southern terminus. (Incidentally, the Loess Hills are themselves a globally significant geological landform, possessing natural features rarely found elsewhere on earth. They will be the subject of a future post). We have searched several of what we consider to be the most promising potential sites for this species in Missouri, though without success. Nevertheless, we remain optimistic that the species might eventually be found in Missouri and has simply been overlooked due to the limited temporal occurrence, small size, rapid running capabilities, and tendency of adults to dart rapidly to the bases of grass clumps where they hide (Pearson et al. 2006). Furthermore, even though the species has not been seen recently in adjacent areas of Nebraska where it has been recorded in the past, it has been seen recently in a few Loess Hill prairie remnants just to the north in Iowa.

A few weeks ago, I was fortunate to receive specific locality information for one of the recently located Iowa populations. Armed with site descriptions, Google maps, photographs, and whatever book learnin’ I had gained about this species, my colleague and I made the long drive to southwestern Iowa in hopes of locating the population for ourselves, seeing adults in their native habitat, and using the learnings we would gain about their habitat preferences and field behavior to augment our efforts to eventually locate the species in northwestern Missouri. At mid-July, we were nearing the end of the adult activity period, but adults had been observed at the site the weekend prior, so we felt reasonably confident that adults might still be found. Additionally, fresh off of our recent success at locating the related Cicindela cursitans in Missouri (another small, flightless, fast-running species), we were hopeful that we now possessed the proper “search image” to recognize C. celeripes in the field should we have the good fortune to encounter it.

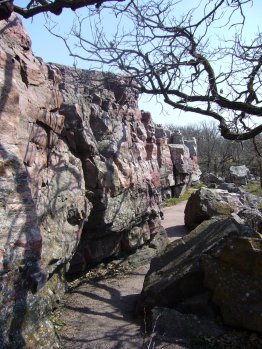

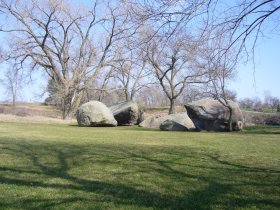

Walking into the area, I was impressed at the extensiveness of the prairie habitat – much larger than any of Missouri’s Loess Hill prairies. The presence of large, charred red-cedar cadavers on the lower slopes revealed active management for prairie restoration. We later learned from the area manager that the restoration area had been acquired from a neighboring landowner who had used the land for grazing and sold it when it became unproductive. I can only imagine the second thoughts that landowner must have had when subsequent burn regimes and woody growth removal prompted a return to the beautifully lush sea of prairie vegetation that now covered the hills. As we approached the area where we decided the beetles must have been seen, we started searching slowly and deliberately – looking carefully for any movement between the clumps of grass. It didn’t appear to be prime habitat for C. celeripes – the vegetation was just so thick, with only small openings among the plants. We continued to scour the area closely but saw nothing, and my optimism began to wane. Wrong spot? – I don’t think so. Bad search image? – hard to imagine, considering its similarity to C. cursitans. Too late? – could be.

After it became obvious we were searching the same gaps in the vegetation repeatedly, I started walking towards a small cut further down the hillside that I had noticed earlier (just visible in the previous photo). I had thought, “That’s tiger beetle land down there!” My optimism increased when I reached the cut, seeing the remains of an old, overgrown 2-track leading through the cut and on down the hillside.  Vegetation was much sparser within and below the cut – it looked perfect. Chris had become distracted taking photographs of something, so I began searching. I’d been in the cut a few minutes when I thought I saw something flash across a bare patch out of the corner of my eye – was that it? It had to be. I carefully inspected around the base of every clump of vegetation at my feet but found nothing. It must have been wishful thinking – just another spider. I continued on down the cut, and within a few more minutes I saw the flash again – this time there was no doubt as to what it was, and I had a lock on it. I started slapping the ground frantically as the little guy darted erratically under, around, and over my hands. In the few seconds while this was happening, I was simultaneously exuberant at having succeeded in finding it, utterly astounded by its speed and evasiveness, and desperately afraid that it was getting away – swift tiger beetle, indeed! Persistence paid off, however, and eventually I had it firmly in my grasp.

Vegetation was much sparser within and below the cut – it looked perfect. Chris had become distracted taking photographs of something, so I began searching. I’d been in the cut a few minutes when I thought I saw something flash across a bare patch out of the corner of my eye – was that it? It had to be. I carefully inspected around the base of every clump of vegetation at my feet but found nothing. It must have been wishful thinking – just another spider. I continued on down the cut, and within a few more minutes I saw the flash again – this time there was no doubt as to what it was, and I had a lock on it. I started slapping the ground frantically as the little guy darted erratically under, around, and over my hands. In the few seconds while this was happening, I was simultaneously exuberant at having succeeded in finding it, utterly astounded by its speed and evasiveness, and desperately afraid that it was getting away – swift tiger beetle, indeed! Persistence paid off, however, and eventually I had it firmly in my grasp.

We would see a total of seven individuals that day. Most of them were within or immediately below the cut, while another individual was seen much further down the 2-track. Mindful of the population declines this species has experienced, we decided to capture just three individuals (even though by this point in the season mating and oviposition would have been largely complete) in hopes that at least one would survive the trip back to the lab for photographs. Our primary goal – to see the species in its native habitat – had been accomplished. We now turned our attention to attempting in situ field photographs.

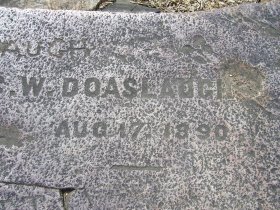

We would see a total of seven individuals that day. Most of them were within or immediately below the cut, while another individual was seen much further down the 2-track. Mindful of the population declines this species has experienced, we decided to capture just three individuals (even though by this point in the season mating and oviposition would have been largely complete) in hopes that at least one would survive the trip back to the lab for photographs. Our primary goal – to see the species in its native habitat – had been accomplished. We now turned our attention to attempting in situ field photographs.  This would prove to be too difficult a task – each beetle we located immediately ran for cover, and flushing it out only caused it to dart to another clump of vegetation. This scenario repeated with each beetle until eventually it simply vanished. We would have to settle for photographs of our captured specimens in a confined arena – a few of which are shown here. The beetles were photographed on a chunk of native loess taken from the site, and no chilling or other “calming” techniques were used. Spomer et al. (2008, Field Guide to the Tiger Beetles of Nebraska and South Dakota) state that C. celeripes is a delicate species that does not do well in captivity.

This would prove to be too difficult a task – each beetle we located immediately ran for cover, and flushing it out only caused it to dart to another clump of vegetation. This scenario repeated with each beetle until eventually it simply vanished. We would have to settle for photographs of our captured specimens in a confined arena – a few of which are shown here. The beetles were photographed on a chunk of native loess taken from the site, and no chilling or other “calming” techniques were used. Spomer et al. (2008, Field Guide to the Tiger Beetles of Nebraska and South Dakota) state that C. celeripes is a delicate species that does not do well in captivity.  It has never been reared, and the larva is unknown. Nevertheless, I placed the chunk of native loess in a plastic tupperware container and transplanted into one corner a small clump of bluegrass from my yard. The soil around the grass clump is kept moist, and every few days I have placed various small insects in the container. Of the three individuals that we brought back, two died within two days. The third individual (these photographs), however, has now survived for four weeks! Moreover, it is a female, and during the past two weeks six larval burrows have appeared in the soil (and another egg was seen on the soil surface just yesterday). Indeed, an egg can be seen in the upper right of the first photo. It remains to be seen whether I will be successful at rearing them to adulthood; however, I’m hopeful this can be accomplished using methods described for C. cursitans (Brust et al. 2005).

It has never been reared, and the larva is unknown. Nevertheless, I placed the chunk of native loess in a plastic tupperware container and transplanted into one corner a small clump of bluegrass from my yard. The soil around the grass clump is kept moist, and every few days I have placed various small insects in the container. Of the three individuals that we brought back, two died within two days. The third individual (these photographs), however, has now survived for four weeks! Moreover, it is a female, and during the past two weeks six larval burrows have appeared in the soil (and another egg was seen on the soil surface just yesterday). Indeed, an egg can be seen in the upper right of the first photo. It remains to be seen whether I will be successful at rearing them to adulthood; however, I’m hopeful this can be accomplished using methods described for C. cursitans (Brust et al. 2005).

Do I still think C. celeripes occurs in Missouri? I don’t know – on one hand, the mixed grass Loess Hill prairie habitats in which the beetle lives in Iowa do extend south into Missouri, and the beetle could be inhabiting them but be easily overlooked for the reasons I’ve already mentioned. However, Missouri’s Loess Hill prairie relicts are small, both in number and in size, and highly disjunct. Such features increase the likelihood of localized extinctions and hamper recolonization through dispersal, especially in flightless species that must traverse unsuitable habitat. With its adult activity period winding down, renewed efforts to locate this species in Missouri will have to wait until next season. Hopefully, the knowledge we gained this season will help this become a reality. For now, the hunt continues…