Welcome to the 2nd issue of House of Herps, the monthly blog carnival devoted exclusively to reptiles and amphibians. The brainchild of Amber Coakley, (Birder’s Lounge), and Jason Hogle (xenogere), this new blog carnival had an auspicious start with the inaugural issue and its 21 contributions – an impressive level of participation for a new carnival. This month the carnival moves off-site, and I am honored to serve as the first off-site host. The enthusiasm continues with issue #2, for which I received 22 submissions from 18 contributors. Ever the taxonomist, I present them to you below grouped by traditional classification¹.

Welcome to the 2nd issue of House of Herps, the monthly blog carnival devoted exclusively to reptiles and amphibians. The brainchild of Amber Coakley, (Birder’s Lounge), and Jason Hogle (xenogere), this new blog carnival had an auspicious start with the inaugural issue and its 21 contributions – an impressive level of participation for a new carnival. This month the carnival moves off-site, and I am honored to serve as the first off-site host. The enthusiasm continues with issue #2, for which I received 22 submissions from 18 contributors. Ever the taxonomist, I present them to you below grouped by traditional classification¹.

¹ It should be noted that modern classification has “evolved” substantially from this traditional classification due to the advent of DNA molecular analyses. For example, lizards are a paraphyletic grouping, and even the class Reptilia has been subsumed within a broader class containing dinosaurs and birds. I stick with the traditional classification here for reasons of familiarity and convenience.

Class AMPHIBIA (Amphibians)

-Order CAUDATA (Salamanders)

California Giant Salamander (Dicamptodon ensatus). At the nature of a man, Ken talks about not one, but two close encounters last fall with this otherwordly-looking creature. The first one he saw was a monster of a salamander, measururing a whopping 12 inches (30 cm) in length as it brazenly lounged on a mountain bike trail. Remaining docile for photographs, imagine Ken’s surprise when the salamander started barking at him when he picked it up to move it to safer ground! In his second encounter, he got to watch one chomp down on a banana slug – mmm tasty!

-Order ANURA (Frogs)

Upland Chorus Frog (Pseudacris feriarum). At Anybody Seen My Focus?, Joan normally only gets to hear the breeding season calls of the chorus frog and his friends who have taken up residence in the water-filled bathtub that serves as a planter in her greenhouse, usually bobbing under the water upon any approach. But on this occasion, he agreed to photographs, even allowing a final closeup.

Upland Chorus Frog (Pseudacris feriarum). At Anybody Seen My Focus?, Joan normally only gets to hear the breeding season calls of the chorus frog and his friends who have taken up residence in the water-filled bathtub that serves as a planter in her greenhouse, usually bobbing under the water upon any approach. But on this occasion, he agreed to photographs, even allowing a final closeup.

Gulf coast toad (Bufo nebulifer). At Dolittle’s Domain, Dr. Doolittle marvels at one of the many toads that she has found parked under the outside light all night (along with the bats and armadillos) during the cold darkness of December. Rather than fleeing the camera flash in the face, he simply hunkered down trying to make himself flatter, apparently thinking that would make him invisible and not realizing that he just looked fatter!

Gulf coast toad (Bufo nebulifer). At Dolittle’s Domain, Dr. Doolittle marvels at one of the many toads that she has found parked under the outside light all night (along with the bats and armadillos) during the cold darkness of December. Rather than fleeing the camera flash in the face, he simply hunkered down trying to make himself flatter, apparently thinking that would make him invisible and not realizing that he just looked fatter!

Northern Cricket Frog (Acris crepitans). HoH‘s own Jason weaves artful writing with stunning photographs to distinguish one of the smallest land vertebrates in North America at xenogere. Despite their ubiquity, these little frogs often go unnoticed due to the smallness of their size, their impressive leap, and their extreme variability. Get a good look at one, however, and you might notice a key feature or two.

Northern Cricket Frog (Acris crepitans). HoH‘s own Jason weaves artful writing with stunning photographs to distinguish one of the smallest land vertebrates in North America at xenogere. Despite their ubiquity, these little frogs often go unnoticed due to the smallness of their size, their impressive leap, and their extreme variability. Get a good look at one, however, and you might notice a key feature or two.

American Bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana). At Willow House Chronicles, barefootheart looks at frogs on the opposite end of the size spectrum, in fact North America’s largest frog living in an increasingly naturalized man-made pond in eastern Ontario. These behemoths are more frequently heard than seen by their distinctive “yelp” and splash in response to being approached. If you are lucky enough to get as good a look as barefootheart did, you might be able to distinguish male from female by looking at its eyes, ears, and throat.

American Bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana). At Willow House Chronicles, barefootheart looks at frogs on the opposite end of the size spectrum, in fact North America’s largest frog living in an increasingly naturalized man-made pond in eastern Ontario. These behemoths are more frequently heard than seen by their distinctive “yelp” and splash in response to being approached. If you are lucky enough to get as good a look as barefootheart did, you might be able to distinguish male from female by looking at its eyes, ears, and throat.

Class REPTILIA (Reptiles)

-Order TESTUDINES (Turtles)

Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina). We have three contributions dealing with these grizzled, ancient, grotesquely beautiful reptiles. The first one comes from Michelle at Rambling Woods, who shows us how it is possible to tame your pet common snapper (but only to a certain degree). If her story isn’t enough, she also presents a short video clip on the common snapping turtle (

Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina). We have three contributions dealing with these grizzled, ancient, grotesquely beautiful reptiles. The first one comes from Michelle at Rambling Woods, who shows us how it is possible to tame your pet common snapper (but only to a certain degree). If her story isn’t enough, she also presents a short video clip on the common snapping turtle ( REMEMBER – don’t ever try to catch or hold a snapping turtle with your bare hands!). In another post, HoH‘s own Amber talks about her attempts to rescue a snapping turtle at Birder’s Lounge. Fortunately for Amber, the little guy was just a tot – not nearly big enough to prune a digit and thwart Amber’s display of compassion. It’s amazing how a creature so dinosaurian at maturity can still be so cute as a youngster.

REMEMBER – don’t ever try to catch or hold a snapping turtle with your bare hands!). In another post, HoH‘s own Amber talks about her attempts to rescue a snapping turtle at Birder’s Lounge. Fortunately for Amber, the little guy was just a tot – not nearly big enough to prune a digit and thwart Amber’s display of compassion. It’s amazing how a creature so dinosaurian at maturity can still be so cute as a youngster. In the third contribution about these fascinating creatures, Marge at Space Coast Beach Buzz talks about her snap (get it?) decision to adopt one of these animals, only to change her mind after discovering its true identity (and before losing any fingers).

In the third contribution about these fascinating creatures, Marge at Space Coast Beach Buzz talks about her snap (get it?) decision to adopt one of these animals, only to change her mind after discovering its true identity (and before losing any fingers).

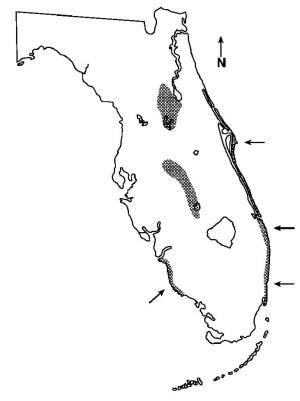

Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas). David at Living Alongside Wildlife notes that while green iguanas falling from trees were a popular news report from the unusual cold snap experienced in the southeatern U.S. last month, they were not the only reptiles so adversely affected. Sea turtles, populations of which have already been compromised by loss of nesting sites, fishing practices, and trash pollution, also found the coastal waters too cold for normal function. While natural hardships may be nature’s way, he argues (quite effectively) that it is our responsibility to help mitigate their effects considering the perilous position in which we’ve placed these majestic animals to begin with.

Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas). David at Living Alongside Wildlife notes that while green iguanas falling from trees were a popular news report from the unusual cold snap experienced in the southeatern U.S. last month, they were not the only reptiles so adversely affected. Sea turtles, populations of which have already been compromised by loss of nesting sites, fishing practices, and trash pollution, also found the coastal waters too cold for normal function. While natural hardships may be nature’s way, he argues (quite effectively) that it is our responsibility to help mitigate their effects considering the perilous position in which we’ve placed these majestic animals to begin with.

Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina). Two contributors submitted posts about these lovable oafs. At A DC Birding Blog, John posted a photo of a box turtle seen at Brigantine Beach. He wonders if their always disgruntled look is a result of him disturbing from their activities. These turtles are easily identified by their bright markings – usually dark brown or olive-colored with bright orange or yellow patterns, dome-shaped carapace, and hinged plastron (bottom part).

Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina). Two contributors submitted posts about these lovable oafs. At A DC Birding Blog, John posted a photo of a box turtle seen at Brigantine Beach. He wonders if their always disgruntled look is a result of him disturbing from their activities. These turtles are easily identified by their bright markings – usually dark brown or olive-colored with bright orange or yellow patterns, dome-shaped carapace, and hinged plastron (bottom part).  Individual turtles have unique designs on their shells, making them identifiable in the field. Turtles can get worms, believe it or not, and Celeste at Celestial Ramblings adds them to the growing list of animals that she has had to de-worm (including herself, ick!). Step-by-step instructions and explicit photos combine to show that this is not an easy job, requiring no less than three people – “just another day at the office.” Hmm – cats look easier!

Individual turtles have unique designs on their shells, making them identifiable in the field. Turtles can get worms, believe it or not, and Celeste at Celestial Ramblings adds them to the growing list of animals that she has had to de-worm (including herself, ick!). Step-by-step instructions and explicit photos combine to show that this is not an easy job, requiring no less than three people – “just another day at the office.” Hmm – cats look easier!

Diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). The diamondback terrapin is the only species of turtle in North America that spends its life in brackish water (salty but less so than sea water). At Kind of Curious, John describes efforts by The Wetlands Institute to prevent vehicle mortality caused by terrapins crossing roads in their attempt to reach higher ground for laying eggs.

Diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). The diamondback terrapin is the only species of turtle in North America that spends its life in brackish water (salty but less so than sea water). At Kind of Curious, John describes efforts by The Wetlands Institute to prevent vehicle mortality caused by terrapins crossing roads in their attempt to reach higher ground for laying eggs.

-Order SQUAMATA

–Suborder LACERTILIA (Lizards)

Common Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris). From Jill at Count Your Chicken! We’re Taking Over! comes this delightful encounter with one of North America’s most charismatic lizards. I’ve had my own experiences with these guys, but I’ve never gotten one to crawl on my hat or – even better – gotten one to pose with me for a photograph!

Common Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris). From Jill at Count Your Chicken! We’re Taking Over! comes this delightful encounter with one of North America’s most charismatic lizards. I’ve had my own experiences with these guys, but I’ve never gotten one to crawl on my hat or – even better – gotten one to pose with me for a photograph!

Prairie Lizard (Sceloporus consobrinus). Near my backyard, Marvin at Nature in the Ozarks presents a nice compendium of this species complimented with beautiful photographs. Marvin not only discusses identification, distribution, life cycle, habitat, and food, but also comments on the recent DNA molecular analyses that have resulted in a reclassification of the former polytopic “fence lizard” and split up the many subspecies into full-fledged species – a man after my taxonomic heart!

Prairie Lizard (Sceloporus consobrinus). Near my backyard, Marvin at Nature in the Ozarks presents a nice compendium of this species complimented with beautiful photographs. Marvin not only discusses identification, distribution, life cycle, habitat, and food, but also comments on the recent DNA molecular analyses that have resulted in a reclassification of the former polytopic “fence lizard” and split up the many subspecies into full-fledged species – a man after my taxonomic heart!

“Culebrilla ciega” (Iberian Worm Lizard) (Blanus cinereus). Javier at macroinstantes writes an artful blog focusing on natural history of the Iberian Peninsula (it is written in Spanish, but Google can easily translate to English for those who need it). In this post, he presents extraordinary photographs of this subterranean reptile that is endemic to the Iberian Peninsula. Traditionally classified in the family Amphisbaenidae, it is now considered to belong to its own family the Blanidae.

“Culebrilla ciega” (Iberian Worm Lizard) (Blanus cinereus). Javier at macroinstantes writes an artful blog focusing on natural history of the Iberian Peninsula (it is written in Spanish, but Google can easily translate to English for those who need it). In this post, he presents extraordinary photographs of this subterranean reptile that is endemic to the Iberian Peninsula. Traditionally classified in the family Amphisbaenidae, it is now considered to belong to its own family the Blanidae.

“Lagartija de Valverde” (The Spanish Algyroides) (Algyroides marchi). Javier (macroinstantes) also writes about this small lizard that was only discovered in 1958. With a global range limited to a few mountain streams in a mountainous area of southern Spain covering less than 2,000 km², it is clasified as endangered on the IUCN Red List. Like so many of the world’s reptiles, its severely fragmented population is suffering declines due to continuing habitat degradation.

“Lagartija de Valverde” (The Spanish Algyroides) (Algyroides marchi). Javier (macroinstantes) also writes about this small lizard that was only discovered in 1958. With a global range limited to a few mountain streams in a mountainous area of southern Spain covering less than 2,000 km², it is clasified as endangered on the IUCN Red List. Like so many of the world’s reptiles, its severely fragmented population is suffering declines due to continuing habitat degradation.

–Suborder SERPENTES (Snakes)

Western Rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis). On the Colorado front range, Sally at Foothills Fancies had three encounters with this aggressive species on her property. Fortunately, Sally has a “nonagression treaty” with rattlesnakes and allows them to go about their business as much as possible. Those that get too close for comfort are humanely relocated rather than simply dispatched. Sadly, many of Sally’s neighbors are not quite so understanding.

Western Rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis). On the Colorado front range, Sally at Foothills Fancies had three encounters with this aggressive species on her property. Fortunately, Sally has a “nonagression treaty” with rattlesnakes and allows them to go about their business as much as possible. Those that get too close for comfort are humanely relocated rather than simply dispatched. Sadly, many of Sally’s neighbors are not quite so understanding.

Texas Indigo Snake (Drymarchon corais erebennus). These snakes do not have any such nonaggression treaty, and David at Living Alongside Wildlife contributes another piece illustrating the rattlenake-eating capabilities for which Indigo snakes are famous. The photographs in the post show a large individual consuming a Western Diamondback Rattlesnake. David explains how these snakes are often identified as blacksnakes and reveals the characters visible on predator and prey that allow their correct identification.

Texas Indigo Snake (Drymarchon corais erebennus). These snakes do not have any such nonaggression treaty, and David at Living Alongside Wildlife contributes another piece illustrating the rattlenake-eating capabilities for which Indigo snakes are famous. The photographs in the post show a large individual consuming a Western Diamondback Rattlesnake. David explains how these snakes are often identified as blacksnakes and reveals the characters visible on predator and prey that allow their correct identification.

Black Rat Snake (Elaphe obsoleta). Right here in my home state, Shelly at Natural Missouri characterizes black rat snakes as one of the most commonly encountered snakes in Missouri. Large snakes reaching up to 6 feet in length, they often end up in basements and cellars in the fall in search of a place to spend the winter – just in time for Halloween! These snakes are often needlessly killed because of their resemblance to the venomous cottonmouth or water moccasin that they superficially resemble. However, Shelly has the same nonaggression treaty with these snakes that Sally has with rattlesnakes (although her husband is not quite so sympathetic).

Black Rat Snake (Elaphe obsoleta). Right here in my home state, Shelly at Natural Missouri characterizes black rat snakes as one of the most commonly encountered snakes in Missouri. Large snakes reaching up to 6 feet in length, they often end up in basements and cellars in the fall in search of a place to spend the winter – just in time for Halloween! These snakes are often needlessly killed because of their resemblance to the venomous cottonmouth or water moccasin that they superficially resemble. However, Shelly has the same nonaggression treaty with these snakes that Sally has with rattlesnakes (although her husband is not quite so sympathetic).

-Order CROCODILIA (Crocodilians)

American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis). David at Living Alongside Wildlife also contributed two pieces on North America’s largest reptile. In his post Gatorzilla, he examines commonly e-mailed pictures and text about so-called “giant” alligators, debunking myths about 25 foot long monsters, clarifying the identity of misidentified Nile crocodiles, and exposing cases of camera trickery.

American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis). David at Living Alongside Wildlife also contributed two pieces on North America’s largest reptile. In his post Gatorzilla, he examines commonly e-mailed pictures and text about so-called “giant” alligators, debunking myths about 25 foot long monsters, clarifying the identity of misidentified Nile crocodiles, and exposing cases of camera trickery.  In his post Mommy Dearest, he recounts his nervewracking experience when he stumbled upon an alligator nest while knee deep in a south Georgia swamp at night. Worse, the babies had hatched! Read the post to see if David got out of there with both of his legs.

In his post Mommy Dearest, he recounts his nervewracking experience when he stumbled upon an alligator nest while knee deep in a south Georgia swamp at night. Worse, the babies had hatched! Read the post to see if David got out of there with both of his legs.

GENERAL HERPETOLOGY

Sometimes simply the act of looking for herps is as enjoyable as the herps that are found. However, it has been a tough January for Bernard at Philly Herping. A particularly cold snap in the first half of what is already the coldest month of the year made herping at his favorite cemetary a lesson in futility. I hope you notice the irony – cemetary?, no sign of life?, cold-bloodedness (okay, okay – ectothermic)?

Sometimes simply the act of looking for herps is as enjoyable as the herps that are found. However, it has been a tough January for Bernard at Philly Herping. A particularly cold snap in the first half of what is already the coldest month of the year made herping at his favorite cemetary a lesson in futility. I hope you notice the irony – cemetary?, no sign of life?, cold-bloodedness (okay, okay – ectothermic)?

I hope you’ve enjoyed this issue of House of Herps. The February issue moves over to xenogere, where Jason’s considerable carnival hosting talents are sure to be on full display. Submit your slimy, scaley, cold-blooded contributions by Febrary 15, and look for the issue to appear by February 18.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2010

Email to a friend

Email to a friend

Most people approach their first blog carnival hosting gig with some trepidation, but the Geek in Question at Fall to Climb has embraced the challenge by volunteering to host two blog carnivals simultaneously. What chutzpah! Clearly, she was up to the task – for issue #3 of An Inordinate Fondness, she introduces us to technical terms such as OMGSHINY and Coleappetite™ in Discovery Zone, with thirteen stories of beetley discovery. She then shows off her “slammer” talent in House of Herps #5: Slime Poetry – deftly pairing poems with prose. I would love to see her do this live!

Most people approach their first blog carnival hosting gig with some trepidation, but the Geek in Question at Fall to Climb has embraced the challenge by volunteering to host two blog carnivals simultaneously. What chutzpah! Clearly, she was up to the task – for issue #3 of An Inordinate Fondness, she introduces us to technical terms such as OMGSHINY and Coleappetite™ in Discovery Zone, with thirteen stories of beetley discovery. She then shows off her “slammer” talent in House of Herps #5: Slime Poetry – deftly pairing poems with prose. I would love to see her do this live! Seabrooke Leckie’s passion for moths is obvious – she is the founder of The Moth and Me and co-author of the soon-to-be-published Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Northeastern North America. Issue #10 of TMaM, Down to the letter, comes home to mama at the Marvelous in Nature – its 24 contributions almost enough to complete the alphabet! Recite your ABCs in lepidopterous fashion with this fine array of contributions.

Seabrooke Leckie’s passion for moths is obvious – she is the founder of The Moth and Me and co-author of the soon-to-be-published Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Northeastern North America. Issue #10 of TMaM, Down to the letter, comes home to mama at the Marvelous in Nature – its 24 contributions almost enough to complete the alphabet! Recite your ABCs in lepidopterous fashion with this fine array of contributions.

It seems like it has been a long time coming, but the

It seems like it has been a long time coming, but the  Also, Jason over at

Also, Jason over at