Alternative title: Rich and Ted’s Excellent Adventure

This is the seventh “Collecting Trip iReport”; this one covering a 5-day trip to Arkansas and Oklahoma from June 7–11, 2019 with my friend and local collecting buddy Richard Thoma. As with all previous “iReports” in this series, this one too is illustrated exclusively with iPhone photographs.

Previous iReports include the following

– 2013 Oklahoma

– 2013 Great Basin

– 2014 Great Plains

– 2015 Texas

– 2018 New Mexico/Texas

– 2018 Arizona

Day 1 – Ozark National Forest, vic. Calico Rock, Arkansas

It’s been many years since I’ve visited these sandstone glades overlooking the White River near Calico Rock. Conditions were partly sunny when we arrived, but water on the ground suggested rain earlier in the day. We had only a short time to start exploring before the wind started blowing up and the smell of rain filled the air. I did manage to beat one Amniscus sexguttata from a branch of living Pinus echinata and collect a couple of Strigoderma sp. from Coreopsis lanceolata flowers before steady rain forced us to retreat.

Day 2 – Ouachita National Forest, Winding Stair Campground & Ouachita Trail, Oklahoma

We walked the trail from the campground S about 2½ miles and back. I started off with Acmaeodera tubulus on Krigia sp. flowers, eventually finding a lot of them on this plant at higher elevations along with a single Acmaeodera ornata, and I beat a few Agrilus cepahlicus off of Cornus drummondii. This had me thinking it would be a good buprestid day, but it wasn’t, the only other species collected being some Chrysobothris cribraria off of small dead Pinus echinata saplings and Pachyschelus laevigatus on Desmodium sp. Also beat a few miscellaneous insects off of Cercis canadensis and Vaccineum arborea and swept some from grasses and other herbaceous plants. Back at the campground I collected Chrysobothris dentipes on the sunny trunks of large, live Pinus echinata trees.

Ouachita National Forest, Talimena Scenic Dr at Big Cedar Vista, Oklahoma

There were lots of native wildflowers like Coreopsis tinctoria and Ratibida columnifera in bloom, so we stopped to check them out. There were lots of butterflies, however, I found only a single Typocerus zebra on Coreopsis lanceolata.

Ouachita National Forest, Winding Stair Campground, Oklahoma

We returned to the campground in the evening to do some blacklighting. I had high hopes, but only five cerambycids came to the lights, all represented by a single individual: Monochamus carolinensis, Acanthocinus obsoletus, Amniscus sexguttatus, Eutrichillus biguttatus, and Leptostylus tranversus (the first four are pine-associates). I also picked up a few other miscellaneous insects.

Day 3 – Medicine Park Primitive Campground, Oklahoma

There wasn’t much insect activity going on in eastern Oklahoma, so we drove out west to the Wichita Mountains for hopefully better luck. We found a small park with a primitive campground in the city of Medicine Park—my first thought was to beat the post oaks dotting the campground, but when I went into the native prairie between the campground and the creek I never came out! Right away I found what must be Acmaeodera ornatoides on flowers of Opuntia sp., then I found more on flowers of Gallardia pulchella along with Acmaeodera mixta. The latter were also on flowers of Thelesperma filifolium along with Acmaeodera neglecta—took a nice series of each, and I also got a few of the latter on flowers of Coreopsis grandiflora. Strangalia sexnotata were on flowers of C. tinctoria and Torilis arvensis, and then on the latter plant I saw a male Strangalia virilis—a Texas/Oklahoma specialty that I’ve never collected before! I spent the next hour looking for these guys and ended up with 3 males and 2 females along with a few Trichiotinus texanus—another Texas/Oklahoma specialty—and a single Agrilaxia sp. nr. flavimana (could be A. texana). One single Typocerus octonotatus was on flowers of Achillea millefolium. I think we may come back here tomorrow—I’d like to look for more S. virilis and beat the post oaks (the reason we stopped here to begin with).

Lake Lawtonka nr. Ma Ballou Point, Oklahoma

We stumbled into this area while looking for stands of Sapindus drummondii (soapberry)—found a small stand along the road, but it was too inaccessible. The same diversity of blooms were present as at the previous spot, so I picked a few longhorns off flowers of Coreopsis grandiflora and Gaillardia pulchella. Super windy, so we didn’t stay long.

Day 4 – Wichita Mountains National Wildlife Refuge, Oklahoma

Before starting the day’s collecting, we wanted to go into the Wichita Mountains National Wildlife Refuge to have a look around. On the way into the refuge we some American bison near the road and had to stop, take photos, and simply admire these massive, majestic beasts. We then went to the Cedar Plantation, where I had visited before back in 2012 and photographed black individuals of Cicindelidia obsoleta vulturina (prairie tiger beetle). No tiger beetles were out now (they come out in the fall), but I’d hoped to maybe see Cylindera celeripes (swift tiger beetle) along the 2-tracks in the area. No such luck—nevertheless, we saw a myriad of interesting insects, including several more Esenbeckia incisuralis (green-eyed horse flies) and a beautiful Trichodes bibalteatus (checkered beetle), the latter of which I photographed on flowers of Ratibida columnifera and Achillea millefolium with the big camera. Afterwards we visited the “prairie dog town” and got marvelous views and photographs of black-tailed prairie dogs.

Medicine Park, Jack Laughter Park, Oklahoma

We’d noticed this spot yesterday because of the old post oaks and wealth of wildflowers blooming up the mountainside. There wasn’t much going on today, however—just a few Acmaeodera mixta on flowers of Gaillardia pulchella. I did find an Anthaxia (Haplanthaxia) sp. on my arm! Otherwise I spent some time photographing the landscape and some geometrid larvae on flowers of Gaillardia pulchella.

Medicine Park Primitive Campground, Oklahoma

We returned to this spot since we had so much luck yesterday. I was hoping to collect more Acmaeodera ornatoides and Strangalia virilis, but there was much less going on today than yesterday—basically didn’t see anything for the first hour and a half. I didn’t give up, however, and kept checking the area where we saw most of the S. virilis yesterday, and eventually I saw another male in the same area as yesterday on the same stand of Torilis arvensis. I found two more males in the same area over the next hour, so three males on the day was a good reward for the time spent looking for them. I also collected Trichodes apivorus and Trichiotinus texanus on flowers of Allium sp. Interestingly, beating the post oaks—the reason why I originally wanted to stop here—produced nothing. So, not very many specimens on the day, but happy with those I did get.

Medicine Park, Jack Laughter Park, Oklahoma

I was pretty much done for the day after spending all morning at the refuge and most of the afternoon at the previous spot, but Rich wanted to take another look at Jack Laughter Park because he’d found some interesting grasshoppers there. As with earlier in the day there were few beetles of interest to me, but I did collect a couple of Trichiotinus texanus on flowers of Cirsium undulatum. I checked out some large post oaks with large dead branches thinking that might be what Strangalia virilis was breeding in but never saw any, and eventually I turned my attention to photographing a few interesting native plants that I found along the way.

Day 5 – Epilogue

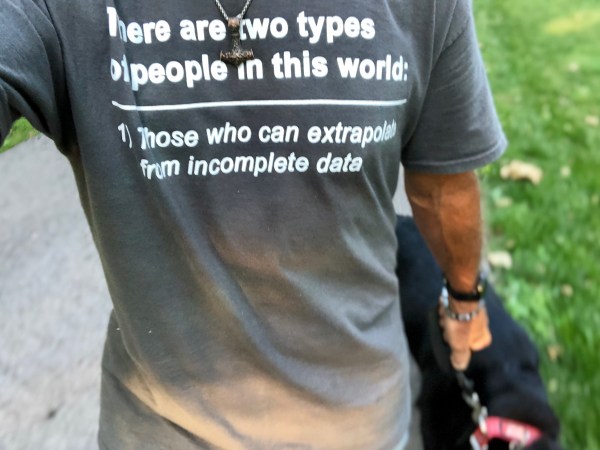

We were tempted to do one last little bit of collecting on the way back to St. Louis, but since had pretty good luck during the last couple of days and the drive alone would take more than nine hours we decided to leave well enough alone and get home at a reasonable hour. A walk with Beauregard when I got home to stretch the post-drive legs was the perfect way to end the mini-vacation.

©️ Ted C. MacRae 2019