Joerie, Joerie, botter en brood,

as ek jou kry, slaat ek jou dood.

Doodlebugs, joerie, shunties, toritos—these are but a few of the many colloquial names given to amusing little creatures that many people know simply as antlions (or translation of such) (Swanson 1996). Larvae of winged insects resembling (but unrelated to) dragonflies, they are best known for their habit of digging smooth-sided, cone-shaped pits in sandy soils and concealing themselves under the sand at the bottom. There, they lay in wait for some small, unsuspecting creature—often an ant—to fall into the pit. When that happens, the hidden antlion bursts forth, using its oversized, sickle-shaped mandibles to “flick” sand at the prey to keep it sliding towards the bottom of the hole. Once it is within reach, the antlion grabs the prey using those same, deadly mandibles (how delightfully morbid!). So otherworldly is their appearance and behavior that, in addition to inspiring children’s charms, they have served as an unmistakable model for the “Ceti eels” featured in Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan!1 Adults of this group, on the other hand, have inspired far less imagination in nomenclature and culture, to the point that even their common name “antlion lacewing” is merely a reference back to their unusual larvae. Even the scientific name of the family—Myrmeleontidae—has failed to garner complete adherence, with “Myrmeleonidae” (who needs the “t”?) and “Myrmelionidae” (perhaps from English-speakers focused on the English spelling of “lion” rather than the Latin spelling of “leo”) still appearing in popular and even scientific literature.

1 Sadly (and ironically), actor Ricardo Montalban, who played the villain Khan Noonien Singh in that movie (reprising a character he played 15 years earlier during the debut season of the Star Trek television series), died just eight days ago at the age of 88. I must confess that I am a life-long Star Trek fan (though not a “Trekkie”), and “Wrath” was certainly among my favorite of the movies, due in large part to Montalban’s steely, venomous portrayal of Kahn. My favorite line occurs as Kahn is about to put a Ceti eel in Chekov’s ear, explaining how they wrap themselves around the victim’s cerebral cortex. He then says, “Later, as they [pauses deliciously] grow…”

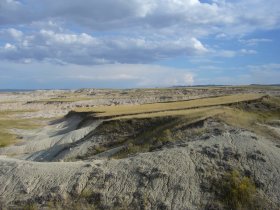

I’ve seen antlion pits on several occasions (especially in recent years as I’ve spent more time in open sand habitats searching for my beloved tiger beetles). However, the pit pictured here—encountered at Borakalalo National Park in South Africa’s North West Province, was the first I’d ever seen in which there was actually an ant inside the pit. The ant was dead, presumably having already been sucked dry by the joerie. I didn’t know it at the time, but southern Africa is a major evolutionary center for antlion lacewings and some of their striking relatives such as spoonwinged and threadwinged lacewings (family Nemopteridae) and silky lacewings (family Psychopsidae) (Grimaldi & Engel 2005). Relatively few of South Africa’s antlions, however, actually dig pits—a habit restricted to species in the genera Hagenomyia, Cueta, and the cosmopolitan Myrmeleon (Scholtz & Holm 1985). Rather, the majority of species have free-living larvae that hide under objects or roam under deep sand from where they emerge to hunt other insects.

I’ve seen antlion pits on several occasions (especially in recent years as I’ve spent more time in open sand habitats searching for my beloved tiger beetles). However, the pit pictured here—encountered at Borakalalo National Park in South Africa’s North West Province, was the first I’d ever seen in which there was actually an ant inside the pit. The ant was dead, presumably having already been sucked dry by the joerie. I didn’t know it at the time, but southern Africa is a major evolutionary center for antlion lacewings and some of their striking relatives such as spoonwinged and threadwinged lacewings (family Nemopteridae) and silky lacewings (family Psychopsidae) (Grimaldi & Engel 2005). Relatively few of South Africa’s antlions, however, actually dig pits—a habit restricted to species in the genera Hagenomyia, Cueta, and the cosmopolitan Myrmeleon (Scholtz & Holm 1985). Rather, the majority of species have free-living larvae that hide under objects or roam under deep sand from where they emerge to hunt other insects.

This adult antlion lacewing came to an ultraviolet light at our encampment on the Geelhoutbos farm near the Waterberg Range (Limpopo Province). Its tremendous size and distinctly patterned wings placed it in the tribe Palparini, of which the genus Palpares is the most diverse. These are the true giants of the family, with forewing lengths that can reach 75 mm (that’s 3 inches, folks!) and both wings bearing conspicuous patterns of black and yellow markings (the yellow doesn’t show well in this photograph due to illumination by the ultraviolet light). The larvae, understandably, are also quite large, and have even been observed to capture ground resting grasshoppers (Capinera 2008). I sent this photograph to Dr. Mervyn Mansell, an expert on African Myrmeleontidae, who kindly identified the individual as a female Palpares lentus, endemic to northern South Africa and Zimbabwe. When queried for more information regarding its biology, Dr. Mansell responded:

This adult antlion lacewing came to an ultraviolet light at our encampment on the Geelhoutbos farm near the Waterberg Range (Limpopo Province). Its tremendous size and distinctly patterned wings placed it in the tribe Palparini, of which the genus Palpares is the most diverse. These are the true giants of the family, with forewing lengths that can reach 75 mm (that’s 3 inches, folks!) and both wings bearing conspicuous patterns of black and yellow markings (the yellow doesn’t show well in this photograph due to illumination by the ultraviolet light). The larvae, understandably, are also quite large, and have even been observed to capture ground resting grasshoppers (Capinera 2008). I sent this photograph to Dr. Mervyn Mansell, an expert on African Myrmeleontidae, who kindly identified the individual as a female Palpares lentus, endemic to northern South Africa and Zimbabwe. When queried for more information regarding its biology, Dr. Mansell responded:

We know nothing about P. lentus, except for distribution records. Nothing is known about its larva or biology, although the larvae of all Palpares and related genera are obviously large, and live freely in sand well concealed and almost impossible to find.

Palpares lentus is one of 42 species of Palparini in southern Africa—half of all known species in the tribe. Nearly two-thirds of them are endemic to “open” biomes in the dry western parts of the subregion (Mansell & Erasmus 2002). This high level of endemism results from the occurrence of large tracts of sand and exposed soil that are conducive to the large sand-dwelling larvae. Eastern parts of the subregion containing forest or thicket biomes are not as favored by antlion lacewings, and consequently the diversity of species in these areas is much lower. Because of their great size, palparine adults are especially vulnerable to predation, with the result that they have evolved elaborately patterned wings to enhance their camouflage—apparently an adaptation to the dappled shade provided by the fine-leafed plants found in these biomes. While many species in the tribe are diurnal, a few in the related genus Palparellus pulchellus and P. ulrike are known to be attracted to light, spending the day resting concealed amongst vegetation. The attraction of this individual to our ultraviolet light suggests Palpares lentus has similar habits.

Everything you want to know about antlions can be found at Mark Swanson’s excellent website, The Antlion Pit. For information specific to Africa, Mervyn Mansell has assembled a checklist of The Antlions (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae) of South Africa, and a nice summary of antlions in Kruger National Park by Dave Rushworth can be found at Destination Kruger Park. I thank Dr. Mansell for his identification of Palpares lentus.

REFERENCES:

Capinera, J. L. (ed.). 2008. Encyclopedia of Entomology, 2nd Edition. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 4346 pp.

Grimaldi, D. and M. S. Engel. 2005. Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press, New York, xv + 755 pp.

Mansell, M. W. and B. F. N. Erasmus. 2002. Southern African biomes and the evolution of Palparini (Insecta: Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae). Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 48 (Suppl. 2):175–184.

Scholtz, C. H. and E. Holm (eds.). 1985. Insects of Southern Africa. Butterworths, Durbin, South Africa, 502 pp.

Swanson, M. 1996. The Antlion Pit: A Doodlebug Anthology. http://www.antlionpit.com/