I have a love-hate affair with Missouri’s Southeast Lowlands (formally known as the Mississippi River Alluvial Basin, but simply called the “bootheel” by most folk in reference to the shape of its boundaries). Of the four main physiogeographic regions in the state, it is by far the most altered. Yes, the Ozark Highlands have been degraded by timber mismanagement, overgrazing, and fire suppression, yet many of its landscapes nevertheless remain relatively intact – just a few burn and chainsaw sessions away from resembling their presettlement condition. The northern Central Dissected Till Plains and western Osage Plains are more disturbed, their prairie landscapes having been largely converted to fields of corn, soybean, and wheat. Still, riparian corridors and prairie habitats ranging from narrow roadsides to sizeable relicts combine to provide at least a glimmer of the regions’ former floral and faunal diversity. The alterations these regions have experienced are significiant, yet they pale in comparison to the near-total, fence-row-to-fence-row conversion that has befallen the Southeast Lowlands. Its rich, deep soils of glacial loess, alluvial silt, and sandy loam originally supported vast cypress-tupelo swamps and wet bottomland forests – massively treed and dripping with biotic diversity. Exposed by relentless logging and an extensive system of drainage ditches and diversion canals, those same soils now support monotonous expanses of soybean, wheat, rice, and cotton. Giant plumes of dark smoke dot the unendingly flat landscape in late spring, as farmers burn wheat stubble in preparation for a double-crop of soybean (the need for which could be obviated by adopting more environmentally benign no-till drillers). Only a tiny fraction of the original swamp acres remain intact, preserved more by default due to their defiant undrainability than by human foresight, and wet bottomland forests now exist only as thin slivers hemmed in by levees along the Mississippi River to the east and the St. Francois River to the west. Solace is hard to find in these remaining tracts – hordes of mosquitoes and deer flies, desperate for blood to nourish their brood, descend upon anyone who dares to enter their realm, while impoverished locals leave behind waste of all manner in their daily quest for fish. The cultural history of the region parallels its natural history – nowhere in the state is the gap between wealth and poverty more evident, a testimony to its checkered history of race and labor relations.

I have a love-hate affair with Missouri’s Southeast Lowlands (formally known as the Mississippi River Alluvial Basin, but simply called the “bootheel” by most folk in reference to the shape of its boundaries). Of the four main physiogeographic regions in the state, it is by far the most altered. Yes, the Ozark Highlands have been degraded by timber mismanagement, overgrazing, and fire suppression, yet many of its landscapes nevertheless remain relatively intact – just a few burn and chainsaw sessions away from resembling their presettlement condition. The northern Central Dissected Till Plains and western Osage Plains are more disturbed, their prairie landscapes having been largely converted to fields of corn, soybean, and wheat. Still, riparian corridors and prairie habitats ranging from narrow roadsides to sizeable relicts combine to provide at least a glimmer of the regions’ former floral and faunal diversity. The alterations these regions have experienced are significiant, yet they pale in comparison to the near-total, fence-row-to-fence-row conversion that has befallen the Southeast Lowlands. Its rich, deep soils of glacial loess, alluvial silt, and sandy loam originally supported vast cypress-tupelo swamps and wet bottomland forests – massively treed and dripping with biotic diversity. Exposed by relentless logging and an extensive system of drainage ditches and diversion canals, those same soils now support monotonous expanses of soybean, wheat, rice, and cotton. Giant plumes of dark smoke dot the unendingly flat landscape in late spring, as farmers burn wheat stubble in preparation for a double-crop of soybean (the need for which could be obviated by adopting more environmentally benign no-till drillers). Only a tiny fraction of the original swamp acres remain intact, preserved more by default due to their defiant undrainability than by human foresight, and wet bottomland forests now exist only as thin slivers hemmed in by levees along the Mississippi River to the east and the St. Francois River to the west. Solace is hard to find in these remaining tracts – hordes of mosquitoes and deer flies, desperate for blood to nourish their brood, descend upon anyone who dares to enter their realm, while impoverished locals leave behind waste of all manner in their daily quest for fish. The cultural history of the region parallels its natural history – nowhere in the state is the gap between wealth and poverty more evident, a testimony to its checkered history of race and labor relations.

Yet, despite its shortcomings, I am continually drawn to this region for my explorations. Driving down the southeastern escarpment of the Ozark Highlands into the Lowlands is like entering another world – a world of grits, fried catfish, and sweet tea, a world where it is odd not to wave to oncoming vehicles on gravel back roads, a world where character is judged by the subtleties of handshake, eye contact, and small talk. Again, its natural history follows suit, with many insects occurring here and nowhere else in Missouri – a distinctly Southern essence in an otherwise decidedly northern state. My recent discussion of Cicindela cursitans in the wet bottomland forests along the Mississippi River is just one example of the unique gems I have encountered in this region. Others include the rare and beautiful hibiscus jewel beetle (Agrilus concinnus), a sedge-mining jewel beetle (genus Taphrocerus) that is new to science (and, due to my sloth, still awaiting formal description), the striking Carolina tiger beetle (Tetracha carolina), and numerous other beetle species not previously recorded from the state. The small and scattered nature of the habitat remnants and often oppressive field conditions make insect study challenging here, but the opportunity for discovery makes this region irresistible.

Yet, despite its shortcomings, I am continually drawn to this region for my explorations. Driving down the southeastern escarpment of the Ozark Highlands into the Lowlands is like entering another world – a world of grits, fried catfish, and sweet tea, a world where it is odd not to wave to oncoming vehicles on gravel back roads, a world where character is judged by the subtleties of handshake, eye contact, and small talk. Again, its natural history follows suit, with many insects occurring here and nowhere else in Missouri – a distinctly Southern essence in an otherwise decidedly northern state. My recent discussion of Cicindela cursitans in the wet bottomland forests along the Mississippi River is just one example of the unique gems I have encountered in this region. Others include the rare and beautiful hibiscus jewel beetle (Agrilus concinnus), a sedge-mining jewel beetle (genus Taphrocerus) that is new to science (and, due to my sloth, still awaiting formal description), the striking Carolina tiger beetle (Tetracha carolina), and numerous other beetle species not previously recorded from the state. The small and scattered nature of the habitat remnants and often oppressive field conditions make insect study challenging here, but the opportunity for discovery makes this region irresistible.

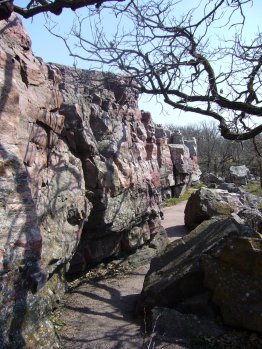

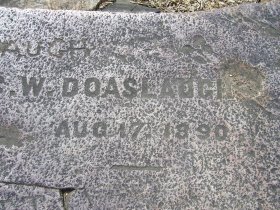

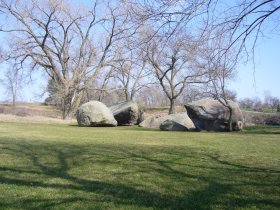

Prior to this season, I had already visited most of the publicly-owned examples of swamp and forest found in the Southeast Lowlands. One natural community, however, that I had not yet seen happened to be one of Missouri’s rarest and most endangered – the sand prairie (I suppose you’ve surmised this by now from the photos). While conducting our recent survey for Cicindela cursitans, I took the opportunity to explore a recently acquired example called Sand Prairie Conservation Area. Geologically, sand prairies lie on our state’s youngest landscape, arising during the relatively recent Pleistocene glacial melts. Tremendous volumes of water from the melting glaciers scoured through loose sands and gravels deposited earlier during the Cretaceous and Tertiary periods by the present day Ohio River (the Mississippi River, much smaller at that time, actually drained northward into Hudson Bay!). After the last of these glacial melts formally ended the “ice age” (only 10,000 years ago), two long sandy ridges were all that remained of the original sand plain. Water drains quickly through the sandy soil of these ridges, which lie some 10 to 20 feet above the surrounding land, creating dry growing conditions favorable for prairie and savanna habitats where only drought-tolerant plants can survive. Dr. Walter Schroeder has conservatively estimated that 60 square miles of sand prairie were present in the Southeast Lowlands at the time of the original land surveys. Because settlement was already occurring at that time, a substantial amount of sand prairie had already likely been converted to agriculture, urban centers, and travel routes to staging areas for access across the swamps. Considering the conversion that might have already taken place, it is possible that as much as 150 to 175 square miles of sand prairie occupied the sand ridges. Sandy areas with higher organic soil content and supporting tallgrasses would have been the first to be converted, since this organic content would have also made them the most suitable for agriculture. Those with lower organic content created drier conditions more suitable for shortgrasses and were the next to be converted. Today, less than 2,000 acres of sand prairie remain – not even 1% of the original amount, and these relicts likely represent the sandiest (and driest) examples of the original sand prairie.

Prior to this season, I had already visited most of the publicly-owned examples of swamp and forest found in the Southeast Lowlands. One natural community, however, that I had not yet seen happened to be one of Missouri’s rarest and most endangered – the sand prairie (I suppose you’ve surmised this by now from the photos). While conducting our recent survey for Cicindela cursitans, I took the opportunity to explore a recently acquired example called Sand Prairie Conservation Area. Geologically, sand prairies lie on our state’s youngest landscape, arising during the relatively recent Pleistocene glacial melts. Tremendous volumes of water from the melting glaciers scoured through loose sands and gravels deposited earlier during the Cretaceous and Tertiary periods by the present day Ohio River (the Mississippi River, much smaller at that time, actually drained northward into Hudson Bay!). After the last of these glacial melts formally ended the “ice age” (only 10,000 years ago), two long sandy ridges were all that remained of the original sand plain. Water drains quickly through the sandy soil of these ridges, which lie some 10 to 20 feet above the surrounding land, creating dry growing conditions favorable for prairie and savanna habitats where only drought-tolerant plants can survive. Dr. Walter Schroeder has conservatively estimated that 60 square miles of sand prairie were present in the Southeast Lowlands at the time of the original land surveys. Because settlement was already occurring at that time, a substantial amount of sand prairie had already likely been converted to agriculture, urban centers, and travel routes to staging areas for access across the swamps. Considering the conversion that might have already taken place, it is possible that as much as 150 to 175 square miles of sand prairie occupied the sand ridges. Sandy areas with higher organic soil content and supporting tallgrasses would have been the first to be converted, since this organic content would have also made them the most suitable for agriculture. Those with lower organic content created drier conditions more suitable for shortgrasses and were the next to be converted. Today, less than 2,000 acres of sand prairie remain – not even 1% of the original amount, and these relicts likely represent the sandiest (and driest) examples of the original sand prairie.

Walking onto the site, I was immediately greeted by an otherworldly expanse of sand dunes, blows, and swales. Ever the entomologist, and with tiger beetles in the fore from hunting C. cursitans, I immediately thought of two dry sand associated species that I have seen in the sand woodlands of nearby Crowley’s Ridge – Cicindela formosa (big sand tiger beetle) and Cicindela scutellaris (festive tiger beetle). These are both so-called “spring-fall” species – i.e., adults are active primarily during spring and fall, so I thought it might be a little late (my first visit was in late June) to see either one. It wasn’t long, however, before I scared up a C. formosa (pictured – but unfortunately facing the setting sun) on one of the dunes. I also encountered one individual of another dry sand associated species, Cicindela lepida (a white “summer” species aptly named ‘ghost tiger beetle’) but was not able to photograph it (I have to say this – I’m a patient man, but photographing tiger beetles is hard. Actually, stalking them until you can get close enough to photograph them is hard. Stalking them until you can get even closer to photograph them with a ‘point and shoot’ – hoping and praying they settle into a pose with the sun on their back because you can’t use the blindingly dinky little built-in flash – just about breaks every last fiber of patience I have within my soul!). Though the site represents a new county record for both species, this is not unexpected, since we have recorded each at multiple dry sand sites near big rivers throughout the state. The occurrence of C. scutellaris at this site, on the other hand, would be significant, and though I did not find it on these two summer visits, I will certainly return this fall to have another look. Cicindela scutellaris has been recorded from just three widely separated locations in the state. Individuals from the two northern Missouri sites are assignable to the more northerly and laterally maculate subspecies C. scutellaris lecontei, but those from the Crowley’s Ridge population (some 20 miles to the west) show an intergrade of characters between C. s. lecontei and the more southerly all-green and immmaculate subspecies C. scutellaris unicolor. I should mention that I believe the classic definition of subspecies (i.e., allopatric populations in which gene flow has been interrupted by geographic barriers) has been grossly misapplied in Cicindelidae taxonomy, with many “subspecies” actually representing nothing more than distinctive extremes of clinal variation. Nevertheless, I am anxious to see if C. scutellaris does occur at Sand Prairie, and if so does it exhibit even more of the “unicolor” influence than does the Crowley’s Ridge population?

Walking onto the site, I was immediately greeted by an otherworldly expanse of sand dunes, blows, and swales. Ever the entomologist, and with tiger beetles in the fore from hunting C. cursitans, I immediately thought of two dry sand associated species that I have seen in the sand woodlands of nearby Crowley’s Ridge – Cicindela formosa (big sand tiger beetle) and Cicindela scutellaris (festive tiger beetle). These are both so-called “spring-fall” species – i.e., adults are active primarily during spring and fall, so I thought it might be a little late (my first visit was in late June) to see either one. It wasn’t long, however, before I scared up a C. formosa (pictured – but unfortunately facing the setting sun) on one of the dunes. I also encountered one individual of another dry sand associated species, Cicindela lepida (a white “summer” species aptly named ‘ghost tiger beetle’) but was not able to photograph it (I have to say this – I’m a patient man, but photographing tiger beetles is hard. Actually, stalking them until you can get close enough to photograph them is hard. Stalking them until you can get even closer to photograph them with a ‘point and shoot’ – hoping and praying they settle into a pose with the sun on their back because you can’t use the blindingly dinky little built-in flash – just about breaks every last fiber of patience I have within my soul!). Though the site represents a new county record for both species, this is not unexpected, since we have recorded each at multiple dry sand sites near big rivers throughout the state. The occurrence of C. scutellaris at this site, on the other hand, would be significant, and though I did not find it on these two summer visits, I will certainly return this fall to have another look. Cicindela scutellaris has been recorded from just three widely separated locations in the state. Individuals from the two northern Missouri sites are assignable to the more northerly and laterally maculate subspecies C. scutellaris lecontei, but those from the Crowley’s Ridge population (some 20 miles to the west) show an intergrade of characters between C. s. lecontei and the more southerly all-green and immmaculate subspecies C. scutellaris unicolor. I should mention that I believe the classic definition of subspecies (i.e., allopatric populations in which gene flow has been interrupted by geographic barriers) has been grossly misapplied in Cicindelidae taxonomy, with many “subspecies” actually representing nothing more than distinctive extremes of clinal variation. Nevertheless, I am anxious to see if C. scutellaris does occur at Sand Prairie, and if so does it exhibit even more of the “unicolor” influence than does the Crowley’s Ridge population?

I’ve mentioned previously my weakness as a botanist, a fact I found especially annoying as I explored this new area and found myself unfamiliar with much of the flora that I encountered. I’ve taken photographs and will, over time, attempt to identify them. Still, some plants are unmistakeable, such as this clasping milkweed (Asclepias amplexicaulis, also known as sand milkweed) –

I’ve mentioned previously my weakness as a botanist, a fact I found especially annoying as I explored this new area and found myself unfamiliar with much of the flora that I encountered. I’ve taken photographs and will, over time, attempt to identify them. Still, some plants are unmistakeable, such as this clasping milkweed (Asclepias amplexicaulis, also known as sand milkweed) –  unfortunately well past bloom. Asclepias is a favorite plant genus of mine (I’ve made it a personal goal to locate all 16 of Missouri’s native Asclepias), so you can imagine my delight when I encountered numerous robust green milkweed (Asclepias viridiflora) plants in full bloom. As I approached one of these plants, I noticed the unmistakeable form and color of a milkweed beetle (genus Tetraopes). It didn’t have the look of the common milkweed beetle (Tetraopes tetrophthalmus), which is widespread and abundant throughout Missouri on common milkweed (Ascelpias syriaca), and as soon as I looked more closely, I recognized it to be the much less common Tetraopes quinquemaculatus.

unfortunately well past bloom. Asclepias is a favorite plant genus of mine (I’ve made it a personal goal to locate all 16 of Missouri’s native Asclepias), so you can imagine my delight when I encountered numerous robust green milkweed (Asclepias viridiflora) plants in full bloom. As I approached one of these plants, I noticed the unmistakeable form and color of a milkweed beetle (genus Tetraopes). It didn’t have the look of the common milkweed beetle (Tetraopes tetrophthalmus), which is widespread and abundant throughout Missouri on common milkweed (Ascelpias syriaca), and as soon as I looked more closely, I recognized it to be the much less common Tetraopes quinquemaculatus.  Additional individuals were found not only on A. viridiflora, but also on A. amplexicaulis. The latter is also a suspected host (the larvae are root borers in living plants) in other parts of the species’ range, but in Missouri I’ve found this species associated only with butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosus). These observations suggest not only that A. viridiflora may also be utlized as a host, but that three species of milkweed are serving as such in this part of the state – unusual for a genus of beetles in which most species exhibit a preference for a single milkweed species in any given area. More questions to answer!

Additional individuals were found not only on A. viridiflora, but also on A. amplexicaulis. The latter is also a suspected host (the larvae are root borers in living plants) in other parts of the species’ range, but in Missouri I’ve found this species associated only with butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosus). These observations suggest not only that A. viridiflora may also be utlized as a host, but that three species of milkweed are serving as such in this part of the state – unusual for a genus of beetles in which most species exhibit a preference for a single milkweed species in any given area. More questions to answer!

Amazingly, there were no publicly owned representatives of this community type in Missouri until just recently, when the Missouri Conservation Department acquired Sand Prairie CA through the efforts of the Southeastern Sand Ridge Conservation Opportunity Area, a consortium of private and public agencies dedicated to the conservation and restoration of sand prairies in the Mississippi River Alluvial Basin. Restoration efforts are now underway to promote species that historically occupied native sand prairies on the Sikeston Sand Ridge. Fire is one such management tool, although there seems to be some debate about the role of fire in the history of this natural community. Some have argued that the Southeast Lowland sand prairies are an anthropogenic landscape, created by Native Americans who regularly cleared and burned the land after arriving in the Mississippi River Alluvial Plain. Had it not been for such intervention, the sand ridges communities would have remained sand woodlands and forests, dominated by hickories and oaks. Several lines of evidence – convincingly summarized by Allison Vaughn in “The Origin of Sand Prairies” (June 2008 issue of Perennis, Newsletter of the S.E. Missouri Native Plant Society) – suggest a more natural origin.

Amazingly, there were no publicly owned representatives of this community type in Missouri until just recently, when the Missouri Conservation Department acquired Sand Prairie CA through the efforts of the Southeastern Sand Ridge Conservation Opportunity Area, a consortium of private and public agencies dedicated to the conservation and restoration of sand prairies in the Mississippi River Alluvial Basin. Restoration efforts are now underway to promote species that historically occupied native sand prairies on the Sikeston Sand Ridge. Fire is one such management tool, although there seems to be some debate about the role of fire in the history of this natural community. Some have argued that the Southeast Lowland sand prairies are an anthropogenic landscape, created by Native Americans who regularly cleared and burned the land after arriving in the Mississippi River Alluvial Plain. Had it not been for such intervention, the sand ridges communities would have remained sand woodlands and forests, dominated by hickories and oaks. Several lines of evidence – convincingly summarized by Allison Vaughn in “The Origin of Sand Prairies” (June 2008 issue of Perennis, Newsletter of the S.E. Missouri Native Plant Society) – suggest a more natural origin. These include the presence of rare sand prairie endemics that do not occur in the sand woodlands of nearby Crowley’s Ridge and the fact that the remaining sand prairie relicts have not succeeded back to sand woodland despite 150 years of post-settlement fire suppression. Perhaps the truth lies somewhere in between, with the driest prairies remaining open regardless of fire, while those with somewhat higher organic content in their soils supported shifting mosaics of prairie, savanna, and woodland as fire events (whether natural or anthropogenic) flashed across different areas. Regardless of their history, the sand prairies of the Southeast Lowlands are truly unique communities that deserve protection. Restoration efforts are well underway at Sand Prairie CA, as evidenced by the charred grass clump next to eastern prickly pear (Opuntia humifusa) in the above photo. There is still more work to do, however, as illustrated by this attractively scenic, yet unfortunately exotic Persian silktree (Albizia julibrissin) still remaining on the parcel – emblematic of Man’s pervasive alterations in even the most unique of landscapes.

For further reading on the sand prairies of the Southeast Lowlands, I recommend the excellent article, “A Prairie in the Swamp”, by A. J. Hendershott and this blog entry by the ever-eloquent author of Ozark Highlands of Missouri. In the meantime, so as not to disappoint the botanists who may stumble upon this silly post, I leave you with a few photographs of some of the wildflowers I saw during my visits.

For further reading on the sand prairies of the Southeast Lowlands, I recommend the excellent article, “A Prairie in the Swamp”, by A. J. Hendershott and this blog entry by the ever-eloquent author of Ozark Highlands of Missouri. In the meantime, so as not to disappoint the botanists who may stumble upon this silly post, I leave you with a few photographs of some of the wildflowers I saw during my visits. I consider the plant in the first photograph to be camphorweed (Heterotheca sp., either camporum or subaxillaris), frequntly associated with sandy soils in southern Missouri (especially the Southeast Lowlands). My colleague James informs me the second plant is plains puccoon (Lithospermum caroliniense), another sandy soil associate found primarily in the Lowlands and distinguished from the much more common L. canescens by its robustness and rougher pubescence.

Both of these species were common near the perimeter of the barren sand areas and nearby. The third plant appears to be spotted beebalm (Monarda punctata) (my thanks to michael for the ID). It was confined, as far as I could tell, to a small area in a swale (moister?) away from the barren sand. This plant, a clump-forming perennial that prefers prairies and open sandy soils, is apparently not common in Missouri, having been found primarily in a few eastern counties adjacent to the Mississippi River.

Both of these species were common near the perimeter of the barren sand areas and nearby. The third plant appears to be spotted beebalm (Monarda punctata) (my thanks to michael for the ID). It was confined, as far as I could tell, to a small area in a swale (moister?) away from the barren sand. This plant, a clump-forming perennial that prefers prairies and open sandy soils, is apparently not common in Missouri, having been found primarily in a few eastern counties adjacent to the Mississippi River.