After missing the past three weeks, I was finally able to rejoin the Webster Groves Nature Study Society Botany Group for their weekly Monday outing. It was a good outing for making my return, as the group visited one of Missouri’s most famous and unusual landmarks—Elephant Rocks State Park—on what turned out to be a sunny day with unseasonably balmy conditions. Located in Acadia Valley in the heart of the St. Francois Mountains, the park is named for its main feature—one of the mid-continent’s best examples of an unusual geological feature known as a “tor.” These piles of rounded, weathered granite boulders sitting atop a bedrock mass of the same rock resemble groups of elephants lumbering across the landscape. First shaped underground in 1.5-billion-year-old granite as vertical and horizontal fractures developed in the rock and percolating water softened and degraded the rock adjacent to the cracks, the “core stones” were eventually exposed as erosion removed the overlying layers and the disintegrated rock surround the fractures, exposing the giant boulders at the surface.

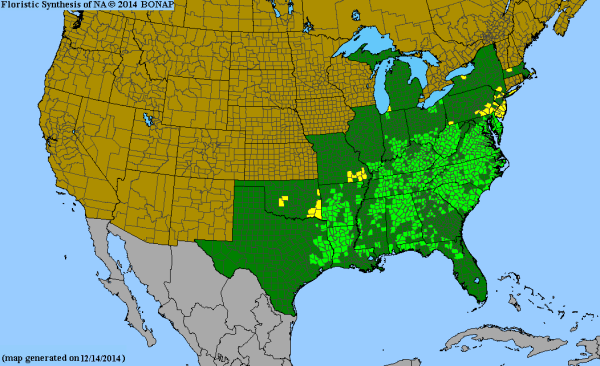

The group explored the area along the Braille Trail, which passes through dry-mesic upland deciduous forest as it circumnavigates the tor. Oaks and hickories—primarily Quercus alba (white oak), post oak (Q. stellata), blackjack oak (Q. marilandica), Carya ovata (shagbark hickory), and C. glabra (pignut hickory)—dominate the canopy, while the understory featured Viburnum rufidulum (rusty blackhaw), Cornus florida (flowering dogwood), Prunus serotina (black cherry). Unusually abundant also was Nyssa sylvatica (black or sour gum). This small tree reaches its northern limit of distribution near St. Louis, Missouri but is more common further south. Winter bud skills are necessary to recognize the species at this time of year, which can be recognized by their alternate arrangement with three reddish-brown scales and three bundle scars. The leaves of this tree turn a brilliant red in the fall, making them desirable for landscape planting.

Like Nyssa sylvatica, Viburnum rufidulum (rusty blackhaw) is also most common south of the Missouri River. However, in contrast to the former, the winter buds of the latter are immediately recognizable by their dark rusty-colored “velvety” buds and opposite arrangement. The tree we saw at the beginning of today’s outing was also heavily laden with fruits, a dark blue-black pruinose drupe.

As we examined the blackhaw tree, we noticed a robust vine entwining its trunk and ascending high into the canopy above. Heavily laden along its length was a crop of fruits that immediately identified the vine as Celastrus scandens (American bittersweet). This native species can be distinguished from the introduced C. orbiculatus (Oriental bittersweet) at this time of year by its terminal fruits with orange instead of yellow dehiscing valves.

The “fruit” theme of the day continued as we veered off the path to look at a rather magnificent specimen of Quercus marilandica (blackjack oak) and saw yet another vine bearing fruit inside its canopy. The opposite leaf remnants had us quickly thinking of some type of honeysuckle (genus Lonicera), and we arrived at Lonicera sempervirens (trumpet honeysuckle) once we noticed the fused perfoliate leaf pairs directly behind the fruits. This native honeysuckle is a desirable species and not to be confused with any of the several invasive introduced species of honeysuckle that can now be found in Missouri.

Another honeysuckle relative, Symphoricarpos orbiculatus (coralberry), was heavily laden with fruit in the shrub layer. Like Lonicera sempervirens, this species is also native to Missouri and should not be confused with the invasive introduced species—especially Lonicera mackii (bush honeysuckle), which it superficially resembles but can be immediately distinguished from during this time of year by its uniquely coral-colored fruits.

As the Braille Trail wrapped around the eastern side of its loop, we passed by a pile of granite boulders—obvious rubble fragments from the quarrying days of the area’s earlier history due to their sharp, angular shapes. Drill holes could be seen in and around the margins of some of the fragments, providing more evidence of their provenance from rock splitting operations before their eventual abandonment, perhaps not being of sufficient quality to warrant further cutting and shaping into building blocks or paving stones before shipment to St. Louis. Lichens growing sparingly on the cut faces indicated that some amount of time had passed since the stone had been cut, but it was a mere fraction of time compared to the densely colonized original exposed surfaces.

Lichens were not the only forms of life taking advantage of new habitat created by past quarrying activities. Two species of ferns were found growing in protected crevices between the boulders, especially those where water was able to collect or seep from. The first was Asplenium platyneuron (ebony spleenwort), with only sterile fronds present but distinguished by the shiny dark rachis (stem) and stipe (stem base) and alternate, basally auriculate (lobed) pinnae (leaflets). The second was at first thought to be another species of Asplenium, possibly A. trichomanes (maidenhair spleenwort), but later determined to be Woodsia obtusa (common woodsia) by virtue of its all green rachis and stipe and much more highly dissected pinnae arranged very nearly opposite on the rachis. We later found the two species again growing close to each other right along the trail—completely unnoticed despite the group having passed them three times already (i.e., 25 person passes!).

A short spur took us to the Engine House ruin—originally built to repair train engines and cars; its granite skeleton still in good condition—before passing by the park’s main geological attraction: the central tor with its famous “elephants”! Standing atop the exposed granite and boulders, I try to let my mind go back half a billion years—an utterly incomprehensible span of time—when the boulders before me are still part of a giant submerged batholith underneath volcanic peaks soaring 15,000 above the Precambrian ocean lapping at their feet; life already a billion years old and dizzyingly diverse yet still confined to those salty waters.

The landscape atop the tor seems sterile and barren, but like the rubble piles below it’s cracks and crevices abound with life. An especially fruticose stand of Vaccinium arboreum (farkleberry) found refuge in a protected area among some of the bigger boulders, their dark blue fruits continuing the “berry” theme of the day and providing an opportunity for the group to sample their flavor and compare to its cultivated blueberry cousins (I found their flavor to be quite pleasing, if somewhat subdued compared to what is my favorite fruit of all). Vaccinium arboreum is the largest of the three species in the genus occurring in Missouri, and the woody stems of larger plants make it quite unmistakable. Smaller plants, however, can be difficult to distinguish from the two other species, in which case the leaf venation can be used—that of V. arboreum being very open. This is another species that finds itself at the northwestern limit of its distribution in the craggy hills of the Ozark Highlands, where it shows a distinct preference for the dry acidic soils found in upland forests overlying igneous or sandstone bedrocks.

Despite this being a botany group outing, I rarely manage to go the entire time go by without finding and pointing out at least one interesting insect. Today, it was an adult Chilocorus stigma (twice-stabbed ladybird beetle) sitting on a Nyssa sylvatica trunk. This is a native ladybird, not to be confused with the introduced and now notorious Harmonia axyridis (Asian ladybird beetle), that lives primarily in forest habitats and is generally considered to be a beneficial species (although not sold for commercial use in orchards or on farms).

©️ Ted C. MacRae 2021