Last Thursday was my birthday, and as has become my custom, I took the day off and went on my ‘Annual Season Opening Birthday Bug Collecting Trip.’ One or two of you might remember how these plans were scrubbed last year by a last minute business trip, during which I discovered Pipestone National Monument in southwest Minnesota. That experience – and the post that I wrote about it – remain high among my all-time favorites. Despite that, nothing was going to derail my plans to go collecting this year, and at 5:30 in the morning I awoke to begin what would turn out to be as enjoyable and successful a day as I could hope for. I had convinced my colleagues and long-time collecting buddies Rich Thoma and Chris Brown to take the day off as well and accompany me down to the lowlands of southeastern Missouri to search for additional localities of the festive tiger beetle – Cicindela scutellaris.

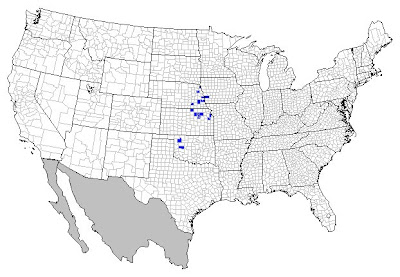

As far as is currently known – C. scutellaris is represented in Missouri by three highly disjuct populations in the extreme northwestern, northeastern, and southeastern corners of the state. The two northern populations are unambigously assignable to the northern subspecies lecontei, although their absence from areas further south in Missouri along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers remains a mystery. The southeastern population apparently represents an intergrade population with influences from both lecontei and the southeastern subspecies unicolor. While this population was discovered many years ago (I first collected it in the mid-1980s), it remained known only from sand forests in Holly Ridge Conservation Area on Crowley’s Ridge. A second population was discovered several years ago on sand exposures in the extreme western lowlands near the Ozark Escarpment when Chris Brown and I began our formal survey of tiger beetles in Missouri, and last year I succeeded in locating several populations of the beetle in the critically imperiled sand prairie relicts located along the spine of the Sikeston Sand Ridge.

This year, we wanted to determine if intergrade populations also occurred on the Malden Sand Ridge – the southernmost expanse of sand exposures in the southeastern lowlands. We didn’t know if they did – presettlement sand prairies were less abundant on the Malden Ridge due to its higher soil organic content. As a result, no sand prairie relicts survived the Malden Ridge’s complete conversion to agriculture. Undeterred, I got onto Google Maps and scoured satellite imagery of the ridge and located several spots that seemed to have potential – even though they were agricultural fields, they appeared to be of sufficient expanse and with enough sand to possibly support populations of the beetle.

This year, we wanted to determine if intergrade populations also occurred on the Malden Sand Ridge – the southernmost expanse of sand exposures in the southeastern lowlands. We didn’t know if they did – presettlement sand prairies were less abundant on the Malden Ridge due to its higher soil organic content. As a result, no sand prairie relicts survived the Malden Ridge’s complete conversion to agriculture. Undeterred, I got onto Google Maps and scoured satellite imagery of the ridge and located several spots that seemed to have potential – even though they were agricultural fields, they appeared to be of sufficient expanse and with enough sand to possibly support populations of the beetle.

So, on the morning of April 23, my ‘Annual Birthday Season Opening Bug Collecting Trip’ began by meeting up with Rich and Chris and driving the 223 miles from Wildwood to Kennett to explore several locations for a beetle based only on the suggestion of a flickering computer screen. The first of these locations was a bust – there was a house constructed right in the middle of the site that wasn’t on the Google Map.  Maybe the beetle occurred here and maybe it didn’t, but the last thing I wanted to do on a Thursday morning was interrupt a homeowner from their morning routine and ask them if we could collect bugs in their front yard. Besides, there was another locality just a couple miles up the road that looked equally promising. We found the spot and drove by slowly – it was an agricultural field that looked like it had been fallow for at least a short time, and although it did not look great (not as much sand as I had hoped) we eventually decided that since we were there we might as well take a look. It wasn’t long before we saw an individual near the highest part of the field, and through a couple hours of exploring and digging adult burrows we had observed a limited number of adults. Success! The landowner happened by while we were there and graciously allowed us to continue our searches. Through her, we learned that the field had been under soybean cultivation during the previous season. This was good news to learn that beetles were inhabiting sand exposures on the Malden Ridge despite its complete conversion to agriculture.

Maybe the beetle occurred here and maybe it didn’t, but the last thing I wanted to do on a Thursday morning was interrupt a homeowner from their morning routine and ask them if we could collect bugs in their front yard. Besides, there was another locality just a couple miles up the road that looked equally promising. We found the spot and drove by slowly – it was an agricultural field that looked like it had been fallow for at least a short time, and although it did not look great (not as much sand as I had hoped) we eventually decided that since we were there we might as well take a look. It wasn’t long before we saw an individual near the highest part of the field, and through a couple hours of exploring and digging adult burrows we had observed a limited number of adults. Success! The landowner happened by while we were there and graciously allowed us to continue our searches. Through her, we learned that the field had been under soybean cultivation during the previous season. This was good news to learn that beetles were inhabiting sand exposures on the Malden Ridge despite its complete conversion to agriculture.

Having confirmed the occurrence of C. scutellaris on the Malden Ridge, we then began driving to the next putative locality some miles north along the ridge. Along the way, Chris spotted a rather large sand expanse in another agricultural field right next to the highway.  Even though I hadn’t detected it in my Google Map search, it looked promising enough to explore, and so we did a quick U-turn and found a place to pull over. This spot can only be described as the ‘festive tiger beetle motherlode’ of southeast Missouri! Even though the field was obviously under active agricultural use, the beetles were abundant within the fairly large expanse of exposed sand within the field (photo below). We were quickly able to collect a sufficient series to document the beetle’s range of variation and set about obtaining additional photographs. I felt fortunate to be able to photograph this mating pair, which nicely illustrates the white labrum of the male (top) versus the dark labrum of the female (bottom) – one character that distinguishes this intergrade population from the similar-appearing six-spotted tiger beetle (C. sexguttata – commonly encountered along woodland trails throughout the eastern U.S., and with both sexes exhibiting a white labrum). Note also how the male is holding his legs out horizontally (a behavior I’ve seen with other mating pairs) and the more heavily padded tarsi on his front legs. The latter specialization is thought to aid in grasping and holding the female (Pearson et al. 2006), although in this instance it clearly is not serving that function, but I have not yet determined for what purpose the horizontal posturing of the front legs is all about (perhaps it is related to alarm behavior).

Even though I hadn’t detected it in my Google Map search, it looked promising enough to explore, and so we did a quick U-turn and found a place to pull over. This spot can only be described as the ‘festive tiger beetle motherlode’ of southeast Missouri! Even though the field was obviously under active agricultural use, the beetles were abundant within the fairly large expanse of exposed sand within the field (photo below). We were quickly able to collect a sufficient series to document the beetle’s range of variation and set about obtaining additional photographs. I felt fortunate to be able to photograph this mating pair, which nicely illustrates the white labrum of the male (top) versus the dark labrum of the female (bottom) – one character that distinguishes this intergrade population from the similar-appearing six-spotted tiger beetle (C. sexguttata – commonly encountered along woodland trails throughout the eastern U.S., and with both sexes exhibiting a white labrum). Note also how the male is holding his legs out horizontally (a behavior I’ve seen with other mating pairs) and the more heavily padded tarsi on his front legs. The latter specialization is thought to aid in grasping and holding the female (Pearson et al. 2006), although in this instance it clearly is not serving that function, but I have not yet determined for what purpose the horizontal posturing of the front legs is all about (perhaps it is related to alarm behavior).

We completed the day by documenting the occurrence of this species on the third of only three sizeable sand prairie relicts that remain on the Sikeston Sand Ridge – a private parcel located a few miles south of the other two preserves. These observations have increased our confidence that C. scutellaris is secure in Missouri’s southeastern lowlands, and that – thankfully – no special conservation measures will be required at this time to assure its continued existence. We also now have enough material on hand to characterize the range of variation exhibited by individuals across this population. We hope this will allow a greater understanding of the relative influence of lecontei populations to the north versus unicolor populations to the south in contributing to the makeup of this population.

We completed the day by documenting the occurrence of this species on the third of only three sizeable sand prairie relicts that remain on the Sikeston Sand Ridge – a private parcel located a few miles south of the other two preserves. These observations have increased our confidence that C. scutellaris is secure in Missouri’s southeastern lowlands, and that – thankfully – no special conservation measures will be required at this time to assure its continued existence. We also now have enough material on hand to characterize the range of variation exhibited by individuals across this population. We hope this will allow a greater understanding of the relative influence of lecontei populations to the north versus unicolor populations to the south in contributing to the makeup of this population.

Since it was my birthday, it was appropriate that I should discover this “gift” next to the rim of my net after I slapped it over a mating pair of beetles. I haven’t found a large number of Native American artifacts during my time in the field, but this has to be most impressive of those that I have found – it is in almost perfect condition, with only the smallest of chips off of one of the lower corners. Edit 5/5/09: After a little research, I believe this to be a spear point from the Archaic period (12,000 to 2,500 years ago).

p.s. – my 100th post!

REFERENCE:

Pearson, D. L., C. B. Knisley and C. J. Kazilek. 2006. A Field Guide to the Tiger Beetles of the United States and Canada. Oxford University Press, New York, 227 pp.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2009