No niche, it seems goes unfilled. Specialization is likely to be pushed to bizarre, beautiful extremes.–E. O. Wilson, The Diversity of Life

Wilson didn’t mention treehoppers specifically when he made the above quote, referring to the exuberance of extreme behavioral and morphological adaptations seen in the biota of the tropics, but he could have just as easily led off with them. Treehoppers (order Hemiptera, family Membracidae) are well-known for their variety of oddly grotesque shapes resulting from a curiously inflated pronotum – presumably having evolved to resemble thorns and buds on their host plants, or the ants that vigorously defend numerous treehopper species in exchange for their sweet honeydew, or perhaps to aid in the dispersal of volatile sex pheromones (an attractive hypothesis but lacking experimental support). Despite inordinate attention in relation to their low economic importance, it remains that the pronotal modifications of many treehoppers are so bizarre that they continue to defy any logical explanation.

I must admit that, despite my passion for beetles, treehoppers were my first love. (Well, actually anything that I could bring home from my solo wanderings in the urban woodlands and vacant lots near my childhood home and keep alive in a terrarium was my first true love, but from an academic standpoint, treehoppers were the first group to arouse my taxonomic interest as I began my transformation from child collector to serious student.) I had just begun graduate school in the Enns Entomology Museum under the late hemipterist Tom Yonke to conduct leafhopper host preference and life history studies, and although far more Cornell drawers in the museum contained Cicadellidae, it was the treehopper drawers that I found myself rifling through each afternoon after completing the day’s thesis duties. Despite their lesser number, the treehopper drawers had recently benefited from the attentions of a previous student, Dennis Kopp, whose efforts during his time at the museum concentrated on collecting treehoppers from throughout Missouri and culminated in the four-part publication, The Treehoppers of Missouri (1973-1974). I was enamored by these little beasts – specifically by their exaggerated pronotum – and started collecting them whenever I could on my forays around the state surveying for leafhoppers. They were closely enough related to leafhoppers to make them relevant to my work, only cooler – like leafhoppers on steroids! With The Treehoppers of Missouri as my bible and my desk located a half dozen footsteps from the largest treehopper collection within a several hundred mile radius, I delved into their taxonomy and, for a time, considered a career as a professional membracid taxonomist.

Fast forward nearly 30 years, and my involvement as a taxonomist is neither professional nor deals with membracids. Beetles have taken over as my focal taxon, and I conduct these studies strictly as an avocation. Still, I continue to collect treehoppers as I encounter them, and although such efforts have been largely opportunistic, I’ve managed to assemble a fairly diverse little collection of these insects as a result of my broad travels. Much of this has occurred in the New World tropics, and it is this region that is the center of diversity for the family Membracidae (fossil evidence suggests that subfamily diversification and subsequent New World radiation began during Tertiary isolation about 65 million years ago after South America separated from Africa, since only the primitive subfamily Centrotinae occurs in both the Old and the New Worlds – all other subfamilies are restricted the New World (Wood 1993)). Every now and then, as I accumulate enough material to fill a Schmidt box, I sit down and study what I’ve collected, comparing it to my meager literature to attempt identifications. For material I collect in eastern North America, this works fairly well, as there have been a number of publications covering different parts of this area. Outside of this area, however, my only hope is to entice one of the few existing membracid specialists into agreeing to look at what I’ve accumulated and ask for their help in providing names, in exchange for which they will be granted retention privileges to benefit their research.

Most recently, I was able to convince Illinois Natural History Survey entomologist Chris Dietrich to take a look at the material I had accumulated during the past ten years or so, which included many specimens from Mexico and a smattering from other world areas, including South Africa. Chris did his doctoral work at North Carolina State University under “Mr. Membracid” himself, Lewis Deitz, and has since been conducting evolutionary and phylogenetic studies on Membracidae and the related Cicadomorpha. I recently received this material back from Chris (photo above), the majority of which he had been able to identify to species – only a few specimens in the more problematic genera were left with a generic ID.

Most recently, I was able to convince Illinois Natural History Survey entomologist Chris Dietrich to take a look at the material I had accumulated during the past ten years or so, which included many specimens from Mexico and a smattering from other world areas, including South Africa. Chris did his doctoral work at North Carolina State University under “Mr. Membracid” himself, Lewis Deitz, and has since been conducting evolutionary and phylogenetic studies on Membracidae and the related Cicadomorpha. I recently received this material back from Chris (photo above), the majority of which he had been able to identify to species – only a few specimens in the more problematic genera were left with a generic ID.

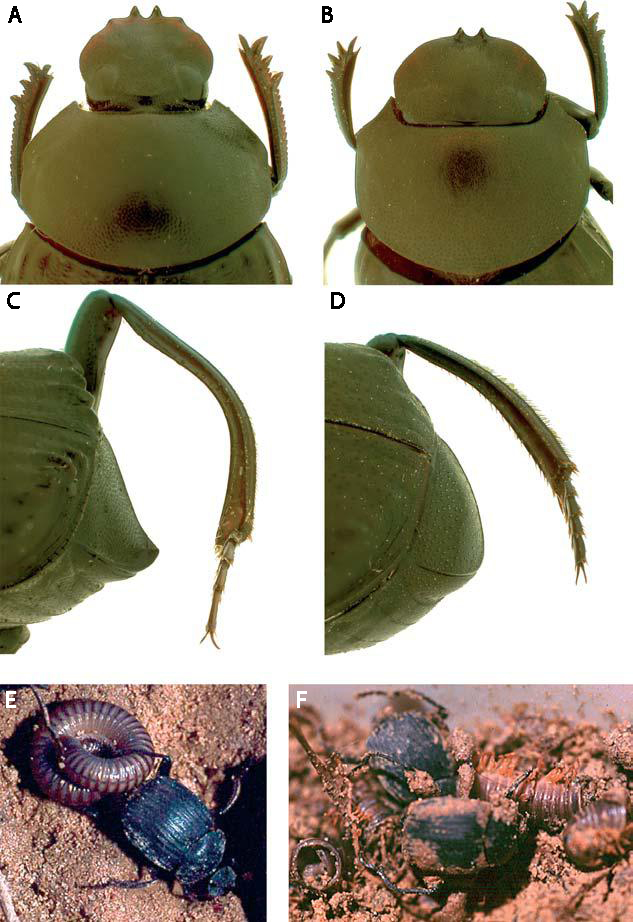

Campylocentrus sp. (Mexico: Oaxaca)

Hyphinoe obliqua (Mexico: Oaxaca)

Poppea setosa (Mexico: Puebla)

Umbonia reclinata (Mexico: Oaxaca)

Umbonia crassicornis male (Mexico: Puebla)

Umbonia crassicornis female (Mexico: Puebla)

The selection of photos here show a sampling of some of the more interesting forms contained within this batch of newly identified material – all of which hail from southern Mexico. Campylocentrus sp. is an example of the primitive subfamily Centrotinae, distinguished among most membracid subfamilies by the exposed scutellum (not covered by the expanded pronotum). Hyphinoe obliqua is an example of the largely Neotropical subfamily Darninae, while Poppea setosa represents one of the more bizarre ant-mimicking species of the subfamily Smiliinae. Umbonia is a diverse genus in the subfamily Membracinae, occurring from the southern U.S. south into South America. Umbonia crassicornis is one of the most commonly encountered species in this genus, with the photos here showing the high degree of sexual dimorphism it exhibits. As membracids go, these species are quite large (10 mm in length from frons to wing apex for Campylocentrus sp. and P. setosa, a slightly larger 11-13 mm for the others); however, the many smaller species in this family are no less extraordinarily ornamented. I’ve also included a photo (below) of one of the drawers from the main collection after incorporating the newly identified material – this drawer represents about half of my treehopper collection, with the largely Nearctic tribe Smiliini and the primitive family Aetalionidae contained in another drawer. In all, the material contained one new subfamily, six new tribes, 13 new genera¹, and 30 new species for my collection. For those with an appetite for brutally technical text, a checklist of the species identified, arranged in my best attempt at their current higher classification, is appended below (any treehopper specialist who happens upon this should feel free to set the record straight on any errors). For each species, the country of origin (and state for U.S. specimens) is indicated along with the number of specimens, and higher taxa new to my collection are indicated with an asterisk(*). Don’t worry, I didn’t type this up just to post it here – it’s a cut/paste job from my newly updated collection inventory for Membracoidea. Happy reading!

¹Wildly off topic, and perhaps of interest only to me, but two of the genera represented in the material are homonyms of plant genera: Oxyrhachis is also a Madagascan genus of Poaceae, and Campylocentrus is a Neotropical genus of Orchidaceae. Scientific names of plants and animals are governed by separate ruling bodies (ICBN and ICZN, respectively), neither of which specifically prohibit (but do recommend against) creating inter-code homonyms. The number of such homonyms is surprisingly high – almost 9,000 generic names have been used in both zoology and botany (13% of the total in botany) (source). Fortunately, there is only one known case of plant/animal homonymy fr BOTH genus- and species-level names – Pieris napi japonica for a subspecies of the gray-veined white butterfly (Pieridae) and Pieris japonica for the popular ornamental plant Japanese andromeda (Ericaceae).

REFERENCES:

Kopp, D. D. and T. R. Yonke. 1973-1974. The treehoppers of Missouri: Parts 1-4. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 46(1):42-64; 46(3):375-421; 46(3):375-421; 47(1):80-130.

Wood, T. K. 1999. Diversity in the New World Membracidae. Annual Review of Entomology 38:409-435.

.

.

Superfamily MEMBRACOIDEA

Family MEMBRACIDAE

Subfamily CENTROTINAE

*Tribe BOOCERINI

*Campylocentrus curvidens (Fairmaire) [Mexico] – 4

Campylocentrus sp. [Mexico] – 1

*Tribe GARGARINI

*Umfilianus declivus Distant [South Africa] – 3

*Tribe OXYRHACHINI

*Oxyrhachis latipes (Buckton) [South Africa] – 1

Tribe PLATYCENTRINI

Platycentrus acuticornis Stål [Mexico] – 11

Platycentrus obtusicornis Stål [Mexico] – 3

Platycentrus brevicornis Van Duzee [USA: California] – 7

Tylocentrus reticulatus Van Duzee [Mexico] – 4

*Tribe TERENTIINI

*Stalobelus sp. [South Africa] – 1

*Subfamily HETERONOTINAE

*Tribe HETERONOTINI

*Dysyncritus sp. [Argentina] – 1

Subfamily MEMBRACINAE

Tribe ACONOPHORINI

Aconophora sp. female [Mexico] – 1

*Guayaquila xiphias (Fabricius) [Argentina] – 7

Tribe HOPLOPHORIONINI

Platycotis vittata (Fabricius) [USA: Arizona, California] – 3

Umbonia crassicornis (Amyot & Serville) [Mexico] – 73

Umbonia reclinata (Germar) [Mexico] – 8

Tribe MEMBRACINI

Enchenopa binotata complex [Mexico] – 1

Enchenopa sp. [Argentina] – 6

Subfamily DARNINAE

Tribe DARNINI

Stictopelta nova Goding [Mexico] – 9

Stictopelta marmorata Goding [USA: Texas] – 1

Stictopelta pulchella Ball [Mexico] – 11

Stictopelta varians Fowler [Mexico] – 3

Stictopelta sp. [USA: Arizona, California] – 5

Stictopelta sp. [Mexico] – 5

Stictopelta spp. [Argentina] – 6

*Sundarion apicalis (Germar) [Argentina] – 2

*Tribe HYPHINOINI

*Hyphenoe obliqua (Walker) [Mexico] – 1

Subfamily SMILIINAE

Tribe AMASTRINI

Vanduzeea triguttata (Burmeister) [USA: Arizona] – 2

Tribe CERESINI

Ceresa nigripectus Remes-Lenicov [Argentina] – 3

Ceresa piramidatis Remes-Lenicov [Argentina] – 4

Ceresa ustulata Fairmaire [Argentina] – 1

Ceresa sp. female [Argentina] – 1

Poppea setosa Fowler [Mexico] – 11

Tortistilus sp. [USA: California] – 1

Tribe POLYGLYPTINI

*Bilimekia styliformis Fowler [Mexico] – 3

Polyglypta costata Burmeister [Mexico] – 18

Tribe SMILIINI

Cyrtolobus acutus Van Duzee [USA: New Mexico] – 1

Cyrtolobus fuscipennis Van Duzee [USA: North Carolina] – 1

Cyrtolobus pallidifrontis Emmons [USA: North Carolina] – 1

Cyrtolobus vanduzei Goding [USA: California] – 4

Cyrtolobus sp. [USA: Arizona] – 2

*Evashmeadea carinata Stål [USA: Arizona] – 4

*Grandolobus grandis (Van Duzee) [USA: Arizona] – 1

Ophiderma sp. [Mexico] – 1

Palonica portola Ball [USA: California] – 4

Telamona decora Ball [USA: Missouri] – 4

Telamona sp. [USA: Texas] – 1

*Telamonanthe rileyi Goding [USA: Texas] – 2

*Telonaca alta Funkhouser [USA: Texas] – 1

Xantholobus sp. [Mexico] – 1

Subfamily STEGASPINAE

Tribe MICROCENTRINI

Microcentrus perditus (Amyot & Serville) [USA: Texas] – 1

Microcentrus proximus (Fowler) [Mexico] – 1

Family AETALIONIDAE

Subfamily AETALIONINAE

Aetalion nervosopunctatum nervosopunctatum Signoret [Mexico] – 9

Aetalion nervosopunctatum minor Fowler [USA: Arizona] – 2

Aetalion reticulatum (Linnaeus) [Argentina, Uruguay] – 26

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2009

I began inspecting the dead trees for the presence of the beetles but didn’t see any at first. Then, I saw something moving right where I had been looking. I had, in fact, looked right over this beetle without seeing it – even though I knew what could be there and what it looked like. I don’t know if the species name (from the Latin obscurus, meaning indistinct) was actually given because of its marvelous cryptic abilities, but it certainly could have been. As I continued to inspect the trees more closely, I found several additional adults – all sitting on trunks that I had just inspected a few minutes prior. I couldn’t help but think of the irony – in collections, Dicerca beetles are quite gaudy and conspicuous appearing, with their shiny, brassy colors and exquisite surface sculpturing (as exemplified by

I began inspecting the dead trees for the presence of the beetles but didn’t see any at first. Then, I saw something moving right where I had been looking. I had, in fact, looked right over this beetle without seeing it – even though I knew what could be there and what it looked like. I don’t know if the species name (from the Latin obscurus, meaning indistinct) was actually given because of its marvelous cryptic abilities, but it certainly could have been. As I continued to inspect the trees more closely, I found several additional adults – all sitting on trunks that I had just inspected a few minutes prior. I couldn’t help but think of the irony – in collections, Dicerca beetles are quite gaudy and conspicuous appearing, with their shiny, brassy colors and exquisite surface sculpturing (as exemplified by  this photo of a pinned specimen in my collection of a similar species, D. asperata). However, in the context of their environment, their coloration and sculpturing helps them blend in and become almost invisible.

this photo of a pinned specimen in my collection of a similar species, D. asperata). However, in the context of their environment, their coloration and sculpturing helps them blend in and become almost invisible.