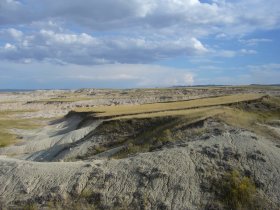

For the past two days I’ve been in Sioux County, Nebraska – just east of Wyoming and just south of South Dakota. As I traveled up through the western panhandle to arrive at this spot, I was pleasantly surprised by the varied terrain – not at all the monotonously flat landscape that I expected. The landscape in this so-called Pine Ridge area is even more surprising – an impressive escarpment drops 1,400′ from the high shortgrass prairie down to an eery badlands below. The escarpment itself is forested with Ponderosa pine and is studded with numerous impressive buttes.

For the past two days I’ve been in Sioux County, Nebraska – just east of Wyoming and just south of South Dakota. As I traveled up through the western panhandle to arrive at this spot, I was pleasantly surprised by the varied terrain – not at all the monotonously flat landscape that I expected. The landscape in this so-called Pine Ridge area is even more surprising – an impressive escarpment drops 1,400′ from the high shortgrass prairie down to an eery badlands below. The escarpment itself is forested with Ponderosa pine and is studded with numerous impressive buttes.  The photos shown here were taken in Sowbelly Canyon – typical of the landscape along the escarpment – and in the badlands below Monroe Canyon a little further west.

The photos shown here were taken in Sowbelly Canyon – typical of the landscape along the escarpment – and in the badlands below Monroe Canyon a little further west.

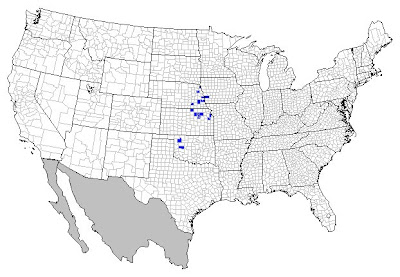

Enough about pines and buttes – my business here is tiger beetles. I met up yesterday with tiger beetle aficionado Matt Brust, who recently took a position here at Chadron State College after finishing his Ph.D. in Lincoln. I’ve been corresponding with Matt for a bit now, and when I told him of my interest in doing a tiger beetle trip through western Nebraska, he was more than willing to show me around and hopefully help me find some of the more unusual species I was looking for. Of course, tops on the priority list was Cicindela nebraskana (prairie long-lipped tiger beetle). This beetle isn’t common anywhere within its range and just sneaks into the northwest corner of Nebraska, where the type locality is located. Until recently, the species was known from very few specimens in Nebraska. Matt did some intensive sampling a few years ago and located a few limited populations in the vicinity of the type locality. Yesterday, he took me to two of these localities, and we succeeded in finding one individual at the first and several at the second. It was at the type locality where I succeeded in getting this field photo.  While admittedly harshly-sunlit, it is as far as I know the only field photograph of the species – all others that I’ve seen have been taken in terraria. I’ll fix it up a bit with Photoshop and re-post once I get back home. This species looks similar to the black morph of Cicindela purpurea audubonii, which co-occurs with C. nebraskana in Nebraska, but it lacks the bright white labrum and elytral markings of the former. Also, as I would learn during these past two days, it can be instantly recognized in the field by its shinier appearance and “stubbier” legs. A few days before my arrival, Matt succeeded in finding the species in the next county to the east, an eastern range extension of about 60 miles, and today I located the species at another new locality between the two. It is gratifying to have played a small role in increasing our knowledge about this unusual species.

While admittedly harshly-sunlit, it is as far as I know the only field photograph of the species – all others that I’ve seen have been taken in terraria. I’ll fix it up a bit with Photoshop and re-post once I get back home. This species looks similar to the black morph of Cicindela purpurea audubonii, which co-occurs with C. nebraskana in Nebraska, but it lacks the bright white labrum and elytral markings of the former. Also, as I would learn during these past two days, it can be instantly recognized in the field by its shinier appearance and “stubbier” legs. A few days before my arrival, Matt succeeded in finding the species in the next county to the east, an eastern range extension of about 60 miles, and today I located the species at another new locality between the two. It is gratifying to have played a small role in increasing our knowledge about this unusual species.

My success with C. nebraskana has come despite uncooperative weather. A series of frontal systems has moved through the area since my arrival, resulting in several rain events and lots of cool, cloudy weather.  Tiger beetles are sun-loving insects, and when it gets too cold or wet the adults dig in and don’t come out until the sun shines through or temps warm enough to trigger them to dig out. Matt had taken me to another locality – a sand embankment – where we might find the beautiful Cicindela lengi (blowout tiger beetle), but it rained prior to our arrival and we saw no activity. I tried finding adult burrows to dig them out, but the rain had obliterated any trace of the diggings, making their burrows impossible to find. We did, however, note an abundance of larval burrows.

Tiger beetles are sun-loving insects, and when it gets too cold or wet the adults dig in and don’t come out until the sun shines through or temps warm enough to trigger them to dig out. Matt had taken me to another locality – a sand embankment – where we might find the beautiful Cicindela lengi (blowout tiger beetle), but it rained prior to our arrival and we saw no activity. I tried finding adult burrows to dig them out, but the rain had obliterated any trace of the diggings, making their burrows impossible to find. We did, however, note an abundance of larval burrows.  I went back to the spot today hoping to see some activity, but thick clouds and cool temps made that unlikely. This is when I decided to “go fishing.” Tiger beetle larval burrows are easily recognized by their perfect circular shape and clean “beveling” around the entrance (1st photo). Burrows of 3rd instars (the last larval instar in tiger beetles) are distinctly larger than those of 2nd instars (2nd photo), while those of 1st instars are smaller still (not shown). Larvae sit at the

I went back to the spot today hoping to see some activity, but thick clouds and cool temps made that unlikely. This is when I decided to “go fishing.” Tiger beetle larval burrows are easily recognized by their perfect circular shape and clean “beveling” around the entrance (1st photo). Burrows of 3rd instars (the last larval instar in tiger beetles) are distinctly larger than those of 2nd instars (2nd photo), while those of 1st instars are smaller still (not shown). Larvae sit at the  burrow entrance and ambush any suitable prey that comes too close. During cool, cloudy weather, however, they drop to the bottom of their burrow – up to a foot or more deep. A technique useful for extracting inactive larvae from their burrows is called fishing and involves inserting a thin grass stem down to the bottom of the burrow in an attempt to coax the larva into “taking the bait” and biting the end of the grass stem (3rd photo). The grass stem is then pulled up rapidly – much like setting the hook when fishing –

burrow entrance and ambush any suitable prey that comes too close. During cool, cloudy weather, however, they drop to the bottom of their burrow – up to a foot or more deep. A technique useful for extracting inactive larvae from their burrows is called fishing and involves inserting a thin grass stem down to the bottom of the burrow in an attempt to coax the larva into “taking the bait” and biting the end of the grass stem (3rd photo). The grass stem is then pulled up rapidly – much like setting the hook when fishing –  in an attempt to pull the larva out of its burrow before it has a chance to let go of the stem. It can take a few tries, but with practice one can more often than not succeed at removing the grotesquely odd, yet beautiful larva (4th photo). Note the huge, heavily sclerotized head with upward facing jaws. The hump in the middle of the back is armed with forward-curved spines that helps the larva avoid being pulled out of the burrow by struggling prey (but they’re not so effective against obsessive cicindelophiles!).

in an attempt to pull the larva out of its burrow before it has a chance to let go of the stem. It can take a few tries, but with practice one can more often than not succeed at removing the grotesquely odd, yet beautiful larva (4th photo). Note the huge, heavily sclerotized head with upward facing jaws. The hump in the middle of the back is armed with forward-curved spines that helps the larva avoid being pulled out of the burrow by struggling prey (but they’re not so effective against obsessive cicindelophiles!).  As I managed to “fish” larvae I placed them in a plastic container with their native soil. In the 5th photo, four larvae have already begun digging new burrows, and one more 3rd instar (L) along with a 2nd instar (R) has just been placed in the container. I’ll bring this container back with me and continue to feed the larvae live insects in the hopes of rearing them to adulthood. I cannot say with certainty that the larvae I collected represent C. lengi – other species that could potentially occur at this site include C. scutellaris (festive tiger beetle) and C. limbata (sandy tiger beetle). However, the locality is known for the abundant occurrence there of C. lengi, so I’m hopeful that that is what I’ve collected – we’ll know in a few weeks. In the meantime, I’ll have additional opportunities to look for this species, along with C. limbata, as I pass through the Sand Hills region later this week.

As I managed to “fish” larvae I placed them in a plastic container with their native soil. In the 5th photo, four larvae have already begun digging new burrows, and one more 3rd instar (L) along with a 2nd instar (R) has just been placed in the container. I’ll bring this container back with me and continue to feed the larvae live insects in the hopes of rearing them to adulthood. I cannot say with certainty that the larvae I collected represent C. lengi – other species that could potentially occur at this site include C. scutellaris (festive tiger beetle) and C. limbata (sandy tiger beetle). However, the locality is known for the abundant occurrence there of C. lengi, so I’m hopeful that that is what I’ve collected – we’ll know in a few weeks. In the meantime, I’ll have additional opportunities to look for this species, along with C. limbata, as I pass through the Sand Hills region later this week.

Tomorrow morning I head to the Black Hills in South Dakota, where I hope to find not only Cicindela longilabris laurentii (Boreal long-lipped tiger beetle) in the high pine forests, but also intergrades between this species and the closely related C. nebraskana in the more open habitats of the middle latitudes. Look for an update in a couple days or so.