While I have specialized in the science of entomology, I am at heart a general naturalist. My whole life, I’ve collected not only insects but many other natural history objects—both biological (e.g., bones, rocks, etc.) and man-made (e.g., books and literature). The latter category, for the past 25 years now, has also included something else—replicas of fossil hominid skulls and crania! This all stated when I had a chance to visit the “Broom Room” at the Transvaal Museum in Pretoria, South Africa, which only came about because of my lifelong interest in the subject of evolution, especially human evolution. I am nowhere close to being an expert in the field; however, I am likely as well versed as can be expected for an avocational enthusiast.

Since that visit to the Broom Room, my collection of hominid skulls and crania has grown slowly (good quality replicas are rather pricey!), but after a quarter-century it has grown to 10 items representing nine of the roughly two dozen known species of extinct humans. The first several sat on my desk—a nod to the now defunct tradition among 18th and 19th century scientists, and as I acquired more I moved them to the tops of bookcases. However, what I have always really wanted to do is display them on a wall arranged to show their putative evolutionary relationships and span of existence in time. With ten examples in hand (and more almost certain to be obtained in the future), now seems like a good time to turn wish into reality.

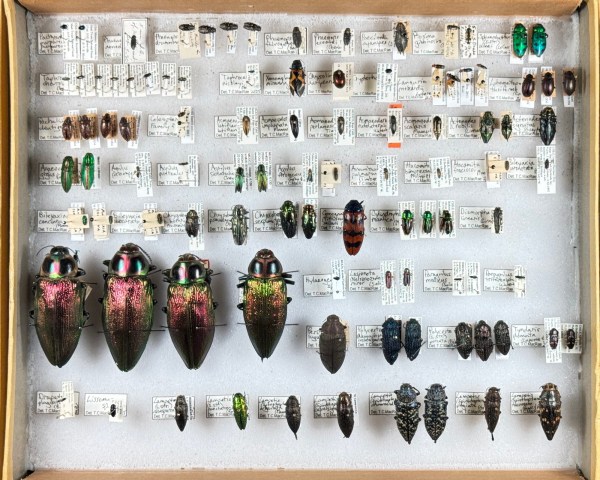

The wall I have in mind in my study is currently occupied by three beautiful, custom, cherry insect cabinets, with the space above measuring 45″ tall × 75″ wide, large enough I think to accommodate the display that I have in mind. Before I can start assembling the display, however, I needed to prepare a Powerpoint mockup of the display to ensure that it accomplishes what I want it to—i.e., 1) the span of time each species existed are shown, 2) their putative relationships are indicated, 3) each species is labeled with the species name, 4) the display is aesthetically pleasing, and 5) most importantly, everything fits within the available space! The 1/10th scale mockup above is what I’ve come up with, with images in the mockup as placeholders for where the actual skull/cranium will be placed. I decided on a vertical axis of time covering the past 7 million years, a horizontal axis indicating “evolutionary grade,” a black vertical bar for each species to indicate the known span of existence (solid representing likely span and dashed representing possible extensions), and lines between species to indicate possible (dashed) or likely (solid) evolutionary relationships. You may quibble with some of my decisions, but the bars and lines represent the spans and relationships that seem most congruent to me. (That said, if you have better information and good sources, please let me know.)

I may still do a little bit of additional tinkering with the mockup, but the next step will be to make the display. My wife has a cricket that we can use to create the bars, lines, and species names, and I can mount small platforms on which to set the skulls/crania in their respective positions. I’ll certainly follow up with a photograph of the actual display when I complete it.

Now, time to start stripping wallpaper!

© Ted C. MacRae 2025