![]() In July 2008, Chris Brown and I made a spur-of-the-moment trip to Hitchcock Preserve near Council Bluffs, Iowa, where only a week earlier Cylindera celeripes (Swift Tiger Beetle), one of North America’s most enigmatic tiger beetles, had just been discovered. Reportedly once common in the blufftop prairies of western Iowa and further west in eastern Nebraska and Kansas, this tiny (6–8 mm in length), flightless beetle has suffered severe population declines over the past 100 years. Only small numbers of individuals have been encountered outside of the type locality (Fort Riley, Kansas) in recent years, and in Nebraska the species is now considered extirpated (Spomer et al. 2008). Our reasons for going to Iowa had to do with our as yet unsuccessful effort to find the species in northwestern Missouri as part of our broader studies of the state’s tiger beetle fauna. Although it had never been recorded from Missouri, we felt there was some chance it might be found in the tiny loess hilltop prairie remnants still remaining in the state at the southern terminus of the Loess Hills landform. We reasoned our failure to find the species might be related to its very small size and rapid running capabilities (giving them more the appearance of small ants or spiders than tiger beetles), limited temporal occurrence, and tendency to hide amongst the bases of grass clumps (Pearson et al. 2006). If we could find the species at a locality where they were known to occur, perhaps an improved search image and better understanding of their precise microhabitat preferences would help us locate the species in Missouri.

In July 2008, Chris Brown and I made a spur-of-the-moment trip to Hitchcock Preserve near Council Bluffs, Iowa, where only a week earlier Cylindera celeripes (Swift Tiger Beetle), one of North America’s most enigmatic tiger beetles, had just been discovered. Reportedly once common in the blufftop prairies of western Iowa and further west in eastern Nebraska and Kansas, this tiny (6–8 mm in length), flightless beetle has suffered severe population declines over the past 100 years. Only small numbers of individuals have been encountered outside of the type locality (Fort Riley, Kansas) in recent years, and in Nebraska the species is now considered extirpated (Spomer et al. 2008). Our reasons for going to Iowa had to do with our as yet unsuccessful effort to find the species in northwestern Missouri as part of our broader studies of the state’s tiger beetle fauna. Although it had never been recorded from Missouri, we felt there was some chance it might be found in the tiny loess hilltop prairie remnants still remaining in the state at the southern terminus of the Loess Hills landform. We reasoned our failure to find the species might be related to its very small size and rapid running capabilities (giving them more the appearance of small ants or spiders than tiger beetles), limited temporal occurrence, and tendency to hide amongst the bases of grass clumps (Pearson et al. 2006). If we could find the species at a locality where they were known to occur, perhaps an improved search image and better understanding of their precise microhabitat preferences would help us locate the species in Missouri.

Fig. 1. Cylindera celeripes (LeConte) adults at: a) Hitchcock Nature Center, Pottawattamie Co., Iowa (13.vii.2008); b) Alabaster Caverns State Park, Woodward Co., Oklahoma (10.vi.2009); c) same locality as “b”, note parasite (possibly Hymenoptera: Dryinidae) protruding from abdomen and ant head attached to right antenna; d) Brickyard Hill Natural Area, Atchison Co., Missouri (27.vi.2009). Photos by C.R.Brown (a) and T.C.MacRae (b-d).

We didn’t realize it at the time, but that trip marked the beginning of a two-year study that would not only see us succeed in finding C. celeripes in Iowa, but also discover new populations in Missouri and northwestern Oklahoma (Figs. 1a–d). With so much new information about the species and the long-standing concerns by many contemporary cicindelid workers about its status, it seemed appropriate to conduct a comprehensive review of the historical occurrence of this species to establish context for its contemporary occurrence and clarify implications for its long term protection and conservation. This was accomplished through compilation of label data from nearly 1,000 specimens residing in the collections of contemporary tiger beetle workers, all of the major public insect museums in the states of Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Texas, and the collections at the U.S. National Museum and Florida State Collection of Arthropods. Collectively, this material is presumed to represent the bulk of material that exists for the species, representing nearly all localities recorded for the species and time periods in which it has been collected.

Label data confirmed the historical abundance of this species, especially in the vicinity of Manhattan and Fort Riley, Kansas; Lincoln and Omaha, Nebraska; and Council Bluffs, Iowa. Hundreds of specimens were routinely collected in the native grassland habitats around these areas during the late 1800s and early 1900s, their abundance documented by entomologists in both journal articles and private letters. One of the most interesting examples of the latter was by Nebraska collector F. H. Shoemaker, who wrote the following in a 1905 letter to R. H. Wolcott:

There is another trip, down the river to the big spring by the railroad track near Albright, then across the river (the heronry route) where we collect hirticollis, repanda, vulgaris [= tranquebarica], cuprascens, and – vat you call ‘im? – celeripes! I took 147 of the latter in an hour and a half Sunday, and the supply was undiminished.

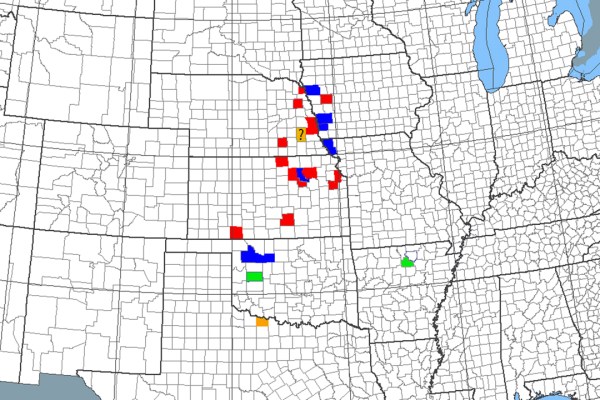

Fig. 8. Historical and currently known geographical occurrence of Cylindera celeripes by county. Red = last record prior to 1920; orange = last record 1941–1960 (“?” = questionable record); green = last record 1991–1996; blue = last record 2005–2011.

Although the recent collections of C. celeripes from near Council Bluffs and through the years near Fort Riley show that the species has managed to persist in these areas, there is little question that it is far less abundant and widespread now than it was in the early 20th century (Fig. 8). Not only are the areas in which present day populations are known to occur limited, but the numbers of individuals seen in them are very low. In Missouri, the species was listed immediately after its discovery in the state as a species of conservation concern with a status of S1 (= “critically imperiled”) due to the highly restricted occurrence of suitable habitat (loess hill prairie) in the state and small populations observed within them. The situation is even worse in Nebraska, where the species has not been seen for nearly 100 years despite dedicated searches by expert contemporary tiger beetle workers such as Matt Brust and Steve Spomer. Considering the near-complete elimination of suitable native grassland habitats by conversion to agriculture and degradation of the few existing remnants due to encroachment by woody vegetation and invasive exotics, the likelihood of finding extant populations of C. celeripes in Nebraska seems remote. Only in the Red Hills of northwestern Oklahoma does the species appear to be secure due to the extensiveness of suitable areas of habitat and robust numbers of individuals observed within them at the present time. An enigmatic record exists from Arkansas, based on a single individual collected near Calico Rock in 1996. This individual represents a significant extension of the known geographical range of the species, but repeated attempts to find the species at that locality during the past year were not successful.

The persistence of populations, albeit small, in multiple areas, along with the occurrence of robust populations in northwestern Oklahoma, makes it unlikely that C. celeripesqualifies for listing as a threatened or endangered species at the federal level. Nevertheless, the limited availability of suitable habitat in many areas and low population numbers found within them clearly suggest that conservation measures are warranted at the state level, especially in Iowa, Kansas and Missouri, to prevent its extirpation from these states. In these states, land management practices should be implemented at sites known to support populations of the beetle in an effort to maintain and expand the native grassland habitats upon which they rely. These include various disturbance factors such as mechanical removal of woody vegetation, judicious use of prescribed burning, and selective grazing (taking care to do so in a manner that minimizes impacts to beetle populations).

REFERENCES:

MacRae, T. C. and C. R. Brown. 2011. Historical and contemporary occurrence of Cylindera (s. str.) celeripes (LeConte) (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae) and implications for its conservation. The Coleopterists Bulletin 65(3):230–241 DOI: 10.1649/072.065.0304

Pearson, D. L., C. B. Knisley and C. J. Kazilek. 2006. A Field Guide to the Tiger Beetles of the United States and Canada. Oxford University Press, New York, 227 pp.

Spomer, S. M., M. L. Brust, D. C. Backlund and S. Weins. 2008. Tiger Beetles of South Dakota & Nebraska. University of Nebraska, Department of Entomology, Lincoln, 60 pp.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2011