Welcome to the 17th “Collecting Trip iReport” covering the first of two planned insect collecting trips to the southwestern U.S. this season—this first one occurring during June 4–13. This was another solo trip, and while it was not as long as I’d hoped, I still managed to visit 15 different localities—one in northwestern Oklahoma, six in northern Arizona, six in southern Utah, and two in southern Nevada.

Per usual, this report assembles field notes largely as they were generated during the trip. They have been lightly “polished” but not substantially modified based on subsequent examination of collected specimens unless expressly indicated by “[Edit…]” in square brackets. Again, I brought my “big” camera and took macro photographs of certain insects in the field that will be featured in future individual posts. However, this “iReport”, as always, features iPhone photographs exclusively. Previous collecting trip “iReports” are:

– 2013 Oklahoma

– 2013 Great Basin

– 2014 Great Plains

– 2015 Texas

– 2018 New Mexico/Texas

– 2018 Arizona

– 2019 Arkansas/Oklahoma

– 2019 Arizona/California

– 2021 West Texas

– 2021 Southwestern U.S.

– 2022 Oklahoma

– 2022 Southwestern U.S.

– 2023 Southwestern U.S.

– 2024 New Mexico: Act 1

– 2024 New Mexico: Act 2

– 2024 New Mexico: Finale

Day 1

I left Kansas City in the morning with two goals: 1) look for Acmaeodera robigo (family Buprestidae) in Texas Co., Oklahoma (based on a 2011 observation posted to BugGuide), and 2) make it to Black Mesa State Park in the far northwestern corner of the Oklahoma panhandle before sunset (to avoid having to set up camp in the dark). It was a long day of driving (mostly through heavy rain), but by the time I arrived at the A. robigo locality, skies were clear and the area was dry. Texas Co. is the largest (and seemingly flattest!) of the three Oklahoma panhandle counties, but I have not collected in the county previously because most of it has been converted to cultivated wheat. This particular location, however, lies within the Beaver River drainage and, thus, features native shortgrass prairie vegetation.

The host plant mentioned in the A. robigo observation, Melampodium lecanthemum (blackfoot daisy—family Asteraceae), was blooming abundantly along the roadsides, so I checked the flowers carefully up one side of the highway and down the other side.

Nothing was seen on the flowers, but given the lateness of the hour and cool temps I did not expect to see anything. Still, I set three white bottle traps in the area within patches of M. leucanthemum and will plan on retrieving them up later this season. With luck, the traps will have attracted adults if the species as they visit the nearby flowers.

Moving west I quickly entered Cimarron Co.—I always enjoy seeing this double-line of utility poles stretching to a seemingly endless horizon at the border between Texas and Cimmaron Counties. The latter is not only the westernmost county in the state, it is also the only county in the U.S. that borders four other states (Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, and Kansas).

I made it to Black Mesa State Park with plenty of daylight left to set up camp. Per usual, after getting camp setup I enjoyed “refreshments” and waited for nightfall to walk the roads looking for nocturnal beetles (or any other critters that might be out and about). I did see an Eleodes sp. (darkling beetle—family Tenebrionidae) early in, but the night was chilly, and the onset of light drizzle put an end to the walk.

This would not be the end of my nighttime hiking, however—at 3am I was awakened by the drone of a motor, and it was loud enough that sleep would be impossible. Thinking it was an inconsiderate camper down at the RV campground, I decided to investigate and discovered it was a water pump within the campground. I decided if I couldn’t sleep, then somebody else would also have to be awakened, namely the campground host. It took the elderly woman a few minutes to come to the door after I rapped a few times on her RV, and I apologized for waking her before explaining the situation. She said she wouldn’t know anything about how to turn it off, to which I replied that I didn’t expect her to know that but I’ll bet somebody does and maybe she could make a call and figure out who that is or this wouldn’t be the last time somebody wakes her at 3am. I figured that would be the last of it, that I’d be awake until morning, and that I would have another nine hours of driving the next day on only three hours of sleep. But, to my relief, about a half hour later a park maintenance vehicle pulled up to the pump house, and a young man turned the motor off (I thanked him profusely). I did eventually get back to sleep and awoke to birdsong and clearing skies.

Day 2

There is a low water bridge at the south entrance to the park that crosses a normally dry creek. However, this time the creek was filled with water with lush growth of sedges and grasses along the water’s edge. This is a perfect situation for Taphrocerus species (family Buprestidae), and at this literal transition point from the eastern to the western fauna I’m not sure what species I might encounter there. Unfortunately, thorough sweeping of the sedges produced no beetles, so the question will for now remain unanswered.

Heading south and then west from the park takes you shortly into the northeastern reaches of New Mexico and the town of Clayton. Whenever I pass through Clayton I like to stop at Mock’s Crossroads Coffee Mill for a bag of freshly ground coffee.

Skimming across the northern reaches of New Mexico for the next several hours was uneventful with no indication of a repeat of the heavy rain that pounded me for much of my drive yesterday across Kansas and Oklahoma. The situation changed, however, as I crossed the Continental Divide on the approach to Farmington.

Sure enough, I once again had the pleasure of driving through driving rain. In addition, I arrived at my next planned spot just north of town (Brown Springs Campground) to find the entrance and main road under several inches of water. No point in trying to collect there, so I continued on towards the next stop (Devils Canyon Campground) in southeast Utah (San Juan Co.) in hopes of arriving early enough to set up camp before dark. Things looked promising as I crossed through the southwestern corner of Colorado towards Monticello, Utah, as patchy clouds filled a sun-filled sky.

The presence of large oval emergence holes in the lower part of the limb confirmed that this tree was, indeed, under attack by such, and stripping the bark around the holes revealed fresh workings from the larvae indicating that some of them may still be inside the tree.

By the time I reached the campground, however, the rain had returned—not hard, but steady. I didn’t relish the thought of setting up camp in the rain and did something I almost never do—heading back into town and spending the night in a motel! At least I was able to enjoy a burger cooked by someone else for a change.

Day 3

Day 3 started off gray and overcast with the threat of more rain, but looking at radar and the areas I was going further west had me optimistic that I would get out of the rain once and for all. My ultimate stop for the day would be Jacob Lake Campground in north-central Arizona (Cocconino Co.), and my plan was to stop at a number of places along the way. Devils Canyon Campground itself, however, was still under clouds, meaning that collecting there would likely not be very productive. Nevertheless, despite last night’s rainout and the continuing cool, wet conditions, I decided to place some traps that I could pick up later in the season and, thus, get at least a sample of the area’s beetle fauna.

The campground lies at ~7000 ft, and I found a ridge with ponderosa pine/gamble oak forest on the slope to one side and pinyon/juniper/oak woodland on the crest of the ridge to the other. On the ponderosa side I set a white bottle trap, and on the pinyon/juniper side I set a sweet red wine-baited jug trap. There wasn’t much in bloom at the time other than a few yellow composites and the occasional Oenothera cespitosa (tufted evening primrose—family Onagraceae) with blossoms still wide open despite the daylight hour due to the overcast, cool conditions.

Coming down off the plateau towards Bluff, Utah, thick low clouds gave way to higher broken clouds with warmer temps (mid-60s). I stopped a few miles west of town at a location where Mont Cazier once collected what was later described as Agrilus utahensis (family Buprestidae) and began sweeping roadside vegetation. While I was sweeping, I encountered three Amannus vittiger (family Cerambycidae) on the flowers of Sphaeralcea coccinea (scarlet globemallow—family Malvaceae) (along with a few meloids and bees for others). The record of A. utahensis was from quite a bit later in the season (late July), so I didn’t really expect to find it (although I was hopeful). However, I did sweep what appears to be Agrilus malvastri.

A short distance west of the stop had me entering northeastern Arizona, and traveling west of Dennehotso on Hwy 160 I encountered patchy, low lying clouds though which beams of bright sunlight lit up the red rocks below and cast a reddish hue on the bottoms of the clouds.

A bit further west on Hwy 160 is a formation apparently known as “Baby Rocks.”

As I drove, I kept my eye out for areas along the highway with stands of plants in bloom, and I found just such at a roadcut on Hwy 98 near mm 325 as I approached Page, Arizona (Cocconino Co.). There was a fair amount of Sphaeralcea coccinea in bloom, off which I collected a handful of Acmaeodera pubiventris lanata and one Amannus vittiger from the flowers. I swept the grasses and other roadside vegetation thoroughly, but that produced nothing. I returned my attention to the Sphaeralcea and swept it thoroughly as well to be sure I didn’t miss anything. Good thin I did, as that turned up one more each of A. p. lanata and A. vittiger as well as a few Agrilus sp. prob. malvastri.

After passing through Page, Arizona, rather than continuing straight west to Jacob Lake Campground, I veered north into Kane Co., Utah to revisit a locality I’d visited a couple of years ago about 23 mi northwest of Page on Hwy 89. The last time I stopped here (late June 2023), I found a few Nanularia brunneata (family Buprestidae) on the stems of Eriogonum inflatum (desert trumpet—family Polygonaceae). That visit was about three weeks later in the season than this time, and not only was the area dry (despite all the rain east of here), but there was very little new growth on any of the E. inflatum plants—just the dried stalks of last year’s growth. Still, there was fresh growth present at the spot, in the form of Ericameria nauseosa (gray rabbitbrush—family Asteraceae), on which I collected a single cryptocephaline leaf beetle, and along the roadside rain shadow in the form of Sphaeralcea parvifolia (small-leaved globemallow), on the flowers of which I collected several more Agrilus sp. prob. malvastri. Eventually, I did find a single E. inflatum plant with small sprouts of new growth on which I found several clytrine leaf beetles. Sweeping the S. parvifolia produced one more Agrilus sp. prob. malvastri, a single Acmaeodera navajoi—a species I collected here abundantly two years earlier, and a series of a very small chrysomelid leaf beetle species that I observed feeding on the foliage.

Once I got a bit further west, the landscape turned green again, indicating recent rains, so I checked iNaturalist for nearby records of E. inflatum that I could check for N. brunnea. There was one a few miles east of Kanab (Kane Co.) and on the way to Jacob Lake Campground, so I stopped by to see if I could find the plants. Unfortunately, the record turned out to be on private property, so I couldn’t go to the precise location. I looked around the area outside the property but didn’t see any plants; however, S. parviflora was blooming abundantly along the roadsides, and sweeping it produced a few more Agrilus sp. prob. malvastri and a couple of small bees (for Mike).

There were also several blooming Opuntia polyacantha var. erinacea (Mojave pricklypear—family Cactaceae), which I checked for Acmaeodera, but I found only one large bee (again, for Mike). With the sun by then dropping close to the horizon, I called it a day and headed for the campground.

I arrived at Jacob Lake Campground (Cocconino Co., Arizona) and got camp setup before dark, which settled in as I was cooking dinner. It was chilly at this relatively high elevation (7900 ft)—temps were already in the mid-50s and were forecast to drop down into the 40s by morning. Despite the chill, I found a Zopherus uteanus (family Zopheridae) and a smaller tenebrionid on a cut stump of Pinus ponderosa (ponderosa pine).

Later, I walked the site—not really expecting to see much because of the chill, but I did find three Iphthiminus lewisii (family Tenebrionidae) on the trunk of a recently fallen P. ponderosa and saw two more on a pine stump.

With three days of travel—the first two mostly rainy and today dry but still quite cool, I’m hoping the forecasted warmer, sunnier conditions for tomorrow and onward come true and I can get this collecting trip in high gear.

Day 4

After morning coffee (and moving to a different campsite—long story!), I went back north a bit to the area near Lefevre Overlook that had been only lightly impacted by the widespread burns that occurred here a few years ago and is showing signs of recovery. It felt “early season” with patchy clouds, moderate temps in the low of mid 70s, and plenty of moisture in the soil with lots of plants in bloom. Insects were not abundant, but with continued beating I collected a couple of Anthaxia sp. (family Buprestidae) and a variety of small clytrines, cryptocepahlines, and curculionids off of Purshia standsburyana (Standsbury’s cliffrose—family Rosaceae) in flower.

As the morning warmed, insects seemed to become a bit more active, although the day continued to feel “early season.” Persistent visual searches and beating of a variety of plants turned up a few small black/yellow Pidonia? (family Cerambycidae), one Acmaeodera diffusa?, and one Anthaxia sp. on flowers of Hymenopappus filifolius (fine-leaved hymenopappus—family Asteraceae); one Agrilus sp. prob. malvastri, another Pidonia?, and one A. diffusa? on flowers of Sphaeralcea ambigua (desert globemallow); several small clytrine and cryptocephaline leaf beetles and curculionid weevils on Quercus gambelii (Gambel oak—family Fagaceae); and several A. diffusa? and a few Anthaxia sp. on flowers of Tetraneuris acaulis (four-nerve daisy—family Asteraceae). Sweeping through the area where the T. acaulis was growing produced nothing further of interest, so I placed a sweet red wine-baited jug trap and a yellow bottle trap in the area—hopefully they will each attract a variety of interesting beetles over the next few months.

A bit further down, the mountain escaped the fire that ravaged many other parts of the mountain. I expected to see much more insect activity, but the opposite instead was the case. This may be related to the lower incidence and diversity of flowering plants, which were likely triggered at the previous spot by the fire. I did find a small area where Sphaeralcea ambigua was blooming abundantly and sweeping through them produced a fine series of Agrilus sp. prob. malvastri along with a few bees (for Mike). I walked up the slope a ways, but there was virtually nothing in bloom—unlike what I had seen at the previous spot. Eventually, I did find a few Hymenopappus filifolia and Tetraneuris acaulis, but the only I beetle I saw on any of them was a single Acmaeodera diffusa? on the latter.

Without anything luring me further up the slope, I worked my way back down towards the car and was about ready to call it a day when I decided to take a gander a bit down the slope—just in case I might see something of interest. Nothing captured my attention, however, so I worked my way over a bit to take a different route back. That’s when I saw it! All day long I had been keeping my eye out for large Utah junipers (Juniperus osteosperma—family Cupressaceae) with thigh-sized main limbs—one of which was dying (not dead), possibly a result of woodboring beetles, and before me was just such a tree!

The presence of large oval emergence holes in the lower part of the limb confirmed that this tree was, indeed, under attack by such, and stripping the bark around the holes revealed fresh workings from the larvae indicating that some of them may still be inside the tree.

I hiked back to the car to get my chainsaw—brought along on the trip just for such an eventuality—and cut a portion of the infested limb out of the tree so I could bring it home and attempt to rear out the adults. My hope is that the species infesting the tree is Semanotus juniperi (family Cerambycidae), a very uncommonly encountered longhorned beetle that breeds in the large limbs of juniper in this area, so I’ll be keeping my fingers crossed. Hauling out the infested bolt along with the chainsaw was a struggle, but eventually I made it back to the car and celebrated a successful last act to what had up to that point been a not too spectacular first full day in the field.

I needed a break after working the chainsaw and hauling out the wood, so I went back to the campsite to enjoy an end-of-the-day “beverage” and eventually dinner. However, part of me was thinking Inshould have collected more of that infested juniper to increase my odds of successfully rearing whatever was infesting it, so I resolved to do exactly that in the morning.

Before dinner as I was gathering kindling, I had noticed a large, fallen ponderosa pine behind the campsite and returned after dark to see if there might be any nocturnal beetles attracted to it. It seemed recently dead, but as I inspected the upper branches more closely I saw that it had been dead long enough that whatever would have been attracted to it had already come and gone. I thought maybe I could find beetles under the bark and began peeling the bark in the trunk. The bark was still intact but was just loose enough that I could peel it off in large sheets. Doing so, however, revealed only a couple of click beetles (family Elateridae). I didn’t see any other fallen or dead trees in the area, but on the trunks of large living ponderosa pines I found a tenebrionoid and several individuals of a Lecontia discicollis (burnt conifer bark beetle (family Boridae). [Edit: thanks to Alex Harmen for the identification on this one!] Nearby was a cut stump of a very large ponderosa pine, and peeling back the thick bark at the base of the stump revealed yet another elaterid species and two darkling beetles. I was hoping to find more Zopherus uteanus, but no such luck!

Day 5

After a morning of the coffee ritual and observing campsite wildlife, I made an ice run at the nearby service station.

I was having second thoughts about taking only a single bolt of wood from cerambycid-infested Utah juniper that I found at the end of yesterday’s collecting and decided to go back to get more of the infested wood to improve the likelihood of successfully rearing adults from the wood. It would not be an easy job—I’d have to haul the chainsaw down the the tree, cut off the two remaining infested bolts, cut the bolts down to cartable pieces, and then haul the chainsaw and wood bolts back to the car, likely requiring several trips. It was worth it, however, because as I was stripping bark to see where I needed to make the initial cut, I encountered an intact cadaver of one of the beetles that had died while trying to emerge from the wood. I carefully extracted the abdomen from the tree and found the head and pronotum in the bark and placed them in a vial, and they without a doubt represent the species I was hoping they were—Semanotus juniperi, a super rare species that very few people have ever collected [tip of the hat to Ron Alten for sharing his knowledge about this beetle with me and enabling me to find this beetle for myself!]. I’ll be able to put the beetle back together when I get home, and I’m hopeful I’ll rear at least a small series of beetles from the wood I’ve collected.

Having carted the additional bolts of wood back to the car and confident in my ability to recognize the work of this species, I looked for—and found—a few more trees that the beetle had infested. However, in each case the workings were old and no beetles were encountered chopping into the wood. I also spent some time looking for much smaller emergence holes in the thick trunk bark of several junipers and carefully shaving the bark to see if I could find another rare longhorned beetle species, Atimia vandykei. I found several galleries that might have been this species, but no beetles or larvae were encountered, leading me to think I might have been a bit late and the adults have mostly emerged. A large, recently dead Pinus edulis (Colorado pinyon pine) also caught my attention, as it looked fresh enough to still contain wood boring beetles that might have infested it. The wood was very hard and difficult to chop into, but I didn’t encounter any larvae of any kind and elected not to collect a bolt or two for rearing. Lastly, I spent some time looking for dead Gambel oaks, which in this area could host Xylotrechus rainei (family Cerambycidae), a recently described species that few have collected. I found several dead stems of the shrubby oak species that contained workings consistent with those of Xylotrechus, but in each case the workings were old and no beetles or larvae were present. This string of “failures” might have seemed like the makings of a bad day, but the success with S. juniperi overshadowed those failures and I left the site happy (though exhausted!).

I returned to the first stop of yesterday to see if I could find junipers in this area infested with S. juniperi, reasoning that since the area had burned a few years ago some of the still-living trees might be stressed, thus making them more vulnerable to infestation. I also wanted to see if the bottle and jug traps I placed yesterday had caught anything of interest (even though it had only been one day). Along the way I picked up a single Anthaxia sp. on the flower of Tetraneuris acaulis and a few Acmaeodera diffusa? on flowers of Sphaeralcea ambigua. There wasn’t anything of interest in either trap, so I set about looking for infested junipers. I found only one, but again the workings were old and no larvae or adults were encountered. I also examined a few dead stems of Gambel oak, but none showed signs of infestation. (I suspect they had been killed by the fire and the damage to the wood by the fire made the stems unsuitable for infestation.) I did, however, find a small more recently dead Colorado pinyon pine that showed signs of recent infestation all along the trunk and collected it for rearing. By then, the day had warmed considerably and I was already exhausted from the morning’s chainsaw session, leading to a loss of motivation to keep looking. I needed a change of pace and decided to head higher up the mountain back into the ponderosa pine forest for some more “traditional” woodboring beetle collecting.

The forest at this site is dominated by ponderosa pine, and the strategy here was straightforward—look for large, dead or dying trees, either standing or recently wind-thrown, and inspect the examine the trunks for woodboring beetles. I came to this spot two years ago in early July, so this time was about four weeks earlier in the season. I had two specific targets (beyond woodboring beetles in general)—Chalcophora (family Buprestidae) and Monochamus (family Cerambycidae). Both of these genera are the subject of molecular studies being conducted by other researchers that I know, and I’ve been promising to send them fresh specimens killed and preserved in ethanol. The first wind-thrown tree I encountered was still green-needled, and I expected to find buprestid beetles all over it. Instead, all I saw were a few small Enoclerus sp. (family Cleridae). Large dead standing trees dotted the open forest, and I carefully approached and circled each one looking for beetles, paying special attention to those in full sunlight. Time after time, however, I was frustrated. Each time, I chopped into the wood a bit to examine what was going on underneath the bark, and while workings were plentiful I never encountered any larvae.

4.2 mi N Jacob Lake on Hwy 89A, Kaibab National Forest, Arizona.

Finally, I approached a large standing dead tree, and perched on its trunk in the sunlight was Chalcophora angulicollis (western sculptured pine borer). I’m happy to give this specimen up for DNA sequencing, especially since I already collected a specimen at this same spot two years ago (before the molecular study began).

I peeled a good portion of bark of the tree it was perched on but found nothing except a large elaterid larva (I wonder if it was Alaus melanops [western eyed elater], a predator or woodboring beetle larvae).

For a long time afterwards that would remain the only beetle I encountered until I found a large standing tree in the early stages of death (needles pale green but not brown) with a female Dicerca tenebrosa (family Buprestidae) searching the trunk, occasionally stopping to probe a crack or crevice with her ovipositor. Patiently waiting at the trunk rewarded me with a second individual within a short period of time.

Another long period of nothingness ensued as I zigzagged from dead tree to dead tree, eventually retracing my steps to the only two trees on which I had found buprestids. Even that failed to produce additional beetles, but as I was standing at one of them I heard a woodpecker persistently pecking and searching and pecking on a nearby tree. The tree looked perfectly healthy at first glance, but I figured the woodpecker had to know something that I didn’t (I’m always willing to learn from locals!) and walked over to the tree. It was immense, and a closer look at the crown revealed a few browning needles scattered throughout the crown. Then a closer look at the trunk revealed several of the same small Enoclerus sp. I saw earlier crawling on it. Woodpeckers and checkered beetles don’t lie, and this tree was clearly under stress and under attack by woodboring beetles. An initial circling of the trunk revealed no other beetles, but then I noticed the gangly antennae and legs of a male/female pair of Monochamus clamator, the male apparently mate-guarding the female. I’ll be happy to contribute one of these specimens to my colleague for DNA sequencing and keep the other for my collection.

By that time, the sun was starting to get rather low in the horizon and I was utterly exhausted after a full day of walking, chopping, chainsawing, and hauling. I passed by the two previously successful trees on the way back to the car, to no avail, and headed back to camp (stopping at the nearby market for a celebratory milkshake before going into the campground).

Day 6

The day’s plan was to head north to the area around Coral Pink Sand Dunes system in southern Utah, but before I left I decided to go down the east slope of the Kaibab Plateau a bit to see it I could find a good transition zone (one that hadn’t burned) from the higher elevation ponderosa pine forest to the juniper/pinyon woodland just below. A few miles east of Jacob Lake, right as I hit 7000’ (there was even a sign to that effect) while descending into the canyon, I saw a small pulloff with ponderosa pine forest (and even some fir) on the east-facing slope to the right and juniper/pinyon/oak woodland on the west-facing slope to the left—perfect! It struck me as a good-looking spot to set some traps, so I set a blue bottle trap in an open area on the juniper/pinyon/oak side of the highway and hid a sweet red wine-baited jug trap in the woodland right above it. I then started beating the patches of Gamble oak hoping for Brachys (family Buprestidae) but finding only a single Anthaxia sp. and several species of clytrine leaf beetles and curculionid weevils. There was a patch of Sphaeralcea ambigua in flower near the pulloff, off which I collected several Acmaeodera diffusa? plus another of those small black /yellow lepturines (Pidonia? sp.) that I found yesterday, and I swept some chunky black dermestids and a couple of bees (for Mike) from the flowers of Hymenopappus filifolia. Next came a long period of nothingness! I found another Utah juniper with damage on the main trunk by Semanotus juniperi, but once again it was old with no larvae or adults encountered after another exhausting chopping session. At this point, I turned my attention to the ponderosa pine forest across the highway, as I’d noticed some large dying/dead trees here and there that I wanted to check for buprestids. Despite checking every dead or declining pine within eyeshot, I didn’t find a single beetle! This, combined with the earlier fruitless chopping session, sapped my motivation, and I started heading back towards the car. Only a few A. diffusa? on the flowers of Opuntia polyacantha var. erinacea and Heterotheca hirsutissima (harsh false goldenaster—family Asteraceae) momentarily captured my attention on the way back.

As I neared the car, I saw a nicely blooming Purshia stansburyana and beat a nice series of Anthaxia (Haplanthaxia) caseyi from it. I’m not sure if the population in this area is assignable to any of the currently recognized subspecies, so I’ll be interested to study them closer and compare them to other unassignable populations I’ve found in other parts of Utah and Arizona. Right before I reached the car, I saw another juniper that begged “chop me.” I complied and then hated myself for it, as the result was the same as all the other junipers I’ve chopped into since finding that first one with Semanotus juniperi in it. With that, I said goodbye to the Kaibab Plateau and headed north towards Ponderosa Grove Campground near Coral Pink Sand Dunes north of Kanab, Utah.

I reached the area around Coral Pink Sand Dunes (Kane Co., Utah) by mid-afternoon. My favorite campground in that area is Ponderosa Grove Campground—it’s large, spacious campsites are not only well shaded by the namesake, unique-for-the-area grove of massive ponderosa pines, but it is also located right across the road from Moquith Mountain Wilderness Study Area, a BLM-managed area with easy access to the northern portion of the Coral Pink Sand Dunes system (for those who may be asking, this portion of the dune system lies outside the boundaries of Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park, which protects the only known habitat of the highly vulnerable Coral Pink Sand Dunes tiger beetle, Cicindela albissima).

After picking a campsite (I was glad to see only a few sites occupied) and unloading my gear, I hightailed it to the dunes with one objective—find Chrysobothris nelsoni (family Buprestidae). I collected this species before on my previous trip here back in late June of 2023, but I spent a day and a half looking for it and managed to only a small handful of specimens. I thought the earlier timing might be better, but Norm Woodley was here a couple of weeks before and did not see the species, giving me reason to be also skeptical.

On the way to the dunes, I set out a yellow bottle trap and sweet red wine-baited jug trap in the sandy juniper/pine woodland bordering the dune. Upon entering the dunes, I immediately started seeing the host plant, Eriogonum alatum (winged buckwheat—family Polygonaceae), a distinctive plant with a basal rosette of linear leaves and, on some plants, a tall stem bearing the inflorescence. One plant in particular, right at the dune entrance, spoke to me saying “look at me.” I don’t know why, but I went over to it, tapped the basal rosette over my net, and off fell a nice large female C. nelsoni! Well, that was fast. I looked at a couple more plants and saw on a second adult (this one a smaller male) sitting head down at the base of the inflorescence stem—two specimens on the first three plants I looked at!

I found quite a few more (although not quite at that same frequency) over the next hour or so before they seemingly just disappeared. I noted the lateness of the hour and wondered if they have a ‘bedtime’—perhaps they burrow into the sand around the base of the plants for the night—and started back towards camp, picking up a few Eleodes caudifera lumbering across the surface of the sand along the way. I decided at that point, now that I had a nice series of the beetle, to bring the “big camera” over the next morning and try to get much nicer photos of the beetles on their host plant that what I can achieve with this iPhone.

It had been a long day by that point—I was both famished and exhausted and needed a bit of time to rest and refuel. I had brought two salmon filets along with me, which should have been enough for two meals, but I was so ravenously hungry that I cooked and ate both.

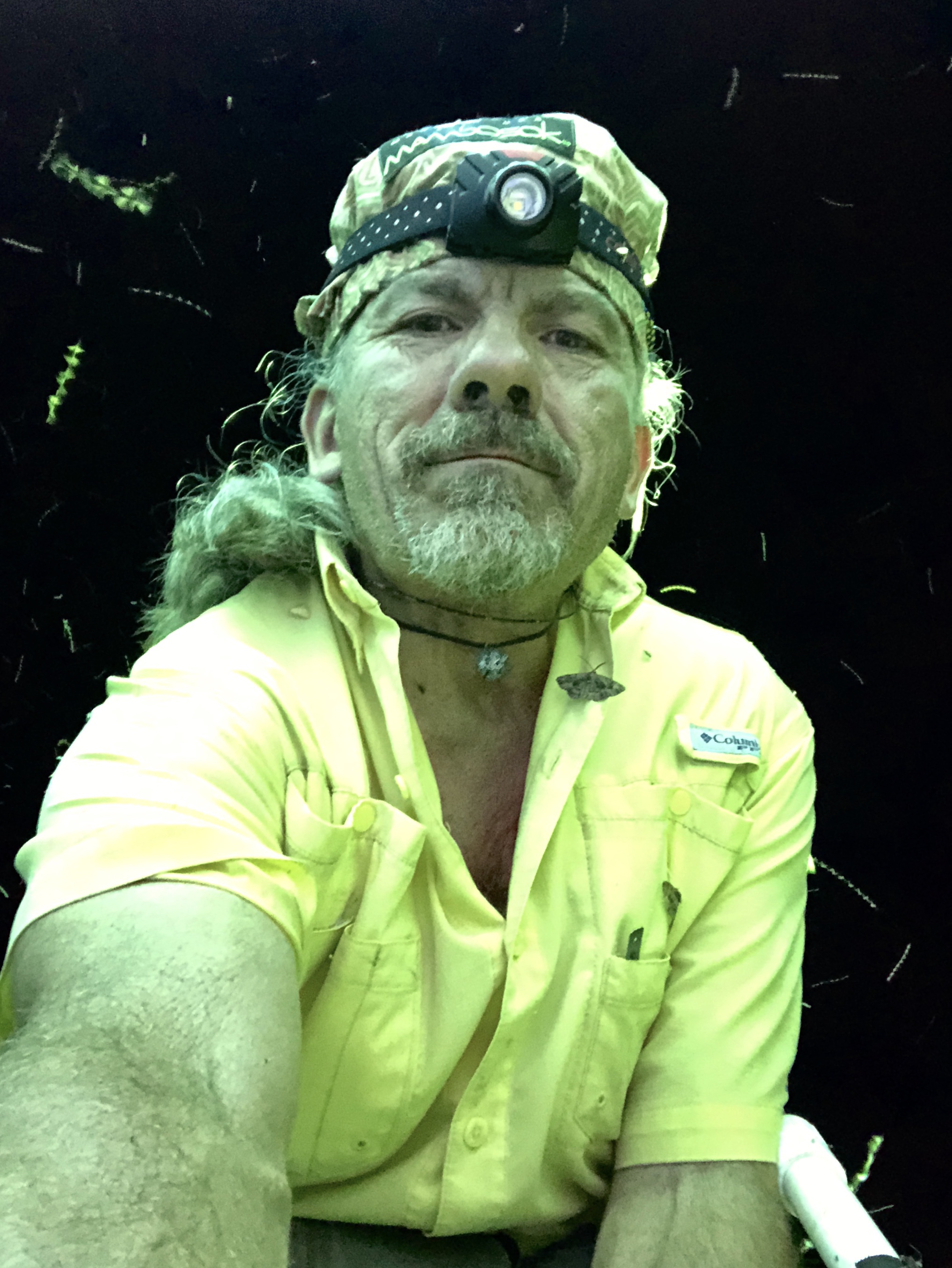

The rest and food gave me a bit of a spark, and as sunset approached I was inspired to set up the blacklights. Conditions were not close to ideal—a waxing gibbous, nearly full moon along with cool(ish) temperatures are usually enough to kill blacklighting. However, it was warmer than the past several nights at Jacob Lake (1300 ft higher elevation), so I compromised by setting up only the two ultraviolet lights (which I can run right off the car batter) but not the mercury-vapor lamp (which would have required hauling out and running the generator).

Not long after I turned the lights on, I noticed the bright, unmistakable glow of a mercury-vapor lamp at the far other end of the campground. I was like “That has to be an entomologist!” so hiked on down to introduce myself. As I entered the campsite, a man approached me and said “Hello, Ted.” Now I’m thinking okay we’ve met before, but I’m a dummy with poor social skills because I don’t recognize him. He said “My name is Mike.” The omission of his last name had me doubly thinking that I was an idiot because the mention of his name still wasn’t enough to trigger my memory of his last name or who he even was. When I asked him his last name, he said Rashko. I recognized that name instantly—he is the person who discovered Acmaeodera rashkoi, recently described by Rick Westcott and one of the species I had targeted on this trip. I told him of my plan and asked him how he knew who I was. It turns out he is a longtime follower of this blog and had seen my license plate (MOBUGS) earlier in the day. He was traveling from his home in Oregon to Flagstaff to meet his family and stopped here to spend the night and see what he could collect. We had a wonderful time chatting about the art of collecting and about colleagues we know (especially Rick, whose ears were burning I’m sure). I showed him the nice series of C. nelsoni that I’d gotten earlier in the day and told him we could go back in the morning before he left so that he could get some. We got so involved talking that we forgot to even look at his sheet to see what insects had come in until a Polyphylla uteanus (Coral Pink Dunes June beetle—family Scarabaeidae) smacked into his head and bumbled its way over to the sheet (Mike let me keep it). A large female Monochamus clamator also landed on the sheet (which Mike kept).

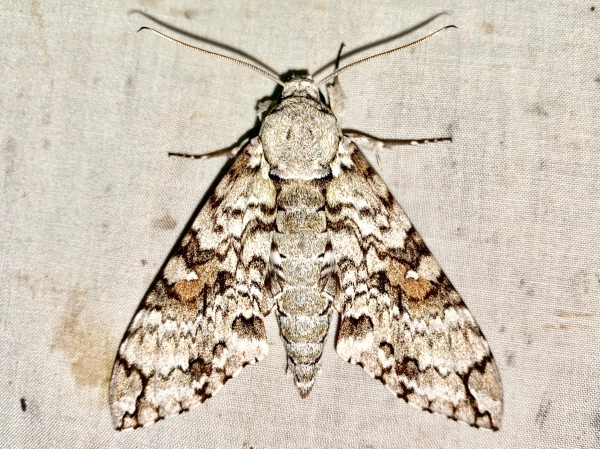

Eventually we said our goodbyes, and I wandered back to my campsite where I was mildly optimistic that my ultraviolet lights had brought in something. Sadly, there were no beetles of interest, but there was a stunning Hyalophora gloveri (Glover’s silk moth—family Saturniidae) and eventually two small white sphingid moths—all of which I kept for Rich Thoma back home. Success for me that night, however, was not yet out of sight. I made a round to inspect the massive trunks of the ponderosa pines dotting the campground and was rewarded with a nice little series of Zopherus uteanus.

I also found a few of the weirdly explanate Embaphion glabrum (family Tenebrionidae) crawling on the ground beneath the trees. A second round to look at the trees yielded no additional beetles, however, so I turned the lights off and turned in.

Day 8

Just as I had promised the night before, I wandered down to Mike’s campsite in the morning to see if he wanted to look for Chrysobothris nelsoni. He was already out looking for “beetles in the bush” around his campsite, and together we worked our way over to the dunes. It didn’t take long for me to see one of the beetles in its host plant, which I pointed out to Mike so he could see it and try to catch it himself. That beetle got away, but almost immediately he saw another one on a neighboring plant and succeeded in capturing it. We saw several more, but unlike the previous evening they were faster and more difficult to catch with the rising late-morning temps. Mike caught a couple more (and I one for the record) but had to leave, so we exchanged contact info and said our goodbyes.

Back at the campsite, I looked around a bit to see what else I might collect. There was a nice diversity of plants in bloom, many which could be expected to be visited by buprestid beetles—Sphaeralcea parviflora (small-leaf globemallow), Opuntia aurea (golden pricklypear cactus), Hymenopappus filifolia, etc., but no beetles were seen. There were clumps of Gamble oak and Amelanchier utahensis (Utah serviceberry—family Rosaceae), but beating them produced nothing. The only thing I found was a recently windthrown branch of Utah juniper, which, when I stripped back some of the bark, proved to be in the early stages of infestation by longhorned beetles, probably a Callidium sp. The lack of insect activity (except for C. nelsoni) presented a quandary—should I stay another night (as planned), or should I pack up and head to my next destination (either Leeds Canyon, Utah or Kyle Canyon, Nevada)? I decided it was already too late in the day to head somewhere else—by the time I got there it would be late in the day, and I didn’t relish the idea of searching for an available campsite late with no reservation at such a late hour. I decided I might as well stay put and make the best of it—which I could do by going back over to the dunes and look for more C. nelsoni. The day’s heat, however, was not only making the beetles very difficult to catch but also starting to get to me. Fortunately, distant thunderclouds came closer and closer until they were directly overhead. Rather than rain, however, it was virga, so I got the best of both worlds—an immediate cooling off that was not only comfortable for me but also settled the beetles down without the rain that would have sent me scurrying back to camp.

In the end, I succeeded in collecting another nice series of specimens.

By then it was mid-afternoon and I was famished, so I headed back to camp to refresh, refuel, rehydrate, and catch up on my field notes. Comically, as I was writing my notes, I happened to be watching one of the common sagebrush lizards (Sceloporus graciosus) that had been hanging around the campsite as it bit at and then rejected some type of insect that was crawling on the logpile next to the firepit. I got up to see what it had rejected, and it turned out to be Danosoma brevicorne (family Elateridae), which I am happy to add to the collection.

After some chill time at the campsite [it was actually very busy—I wrote my field notes from earlier, charged all my devices using an inverter hooked up to the car battery, and downloaded photos from my “big camera” memory card to the computer], I went back to the dunes to see if I could get “big camera” photo of the beetles. It was touch-and-go at the start—shortly after reaching the dunes it started sprinkling and the wind started picking up. All I could do was wait it out, hope conditions improved, and be ready to bolt if the skies opened up. Just as quickly as it started up, however, it blew over, and I was able to start looking for beetles. As with every other time during this visit, it didn’t take long. The first beetle I found was a bit hidden within the crown of the plant, but I was able to carefully move the leaves out of the way without disturbing the beetle and got a nice series of shots. I was happy with the photos, but I wanted photos that were a little less “cluttered.” The perfect opportunity for such arose when I saw a beetle sitting out near the tip of a leaf. It was not in the best position—other leaves were partially blocking it from view, so I carefully grabbed the leaf at the base and gently pulled until it detached from the plant. Fortunately, the beetle wasn’t phased by the tugging and continued to sit calmly on the leaf. I wanted a blurred pink sand background, which I thought would look spectacular behind the brilliant green color of the beetle, so I stuck the base of the leaf in the sand to prop it up and adjusted the angle and distance in concert with my camera and flash settings until I achieved the desired effect. I’m super happy with how some of these photographs turned out, so look for them to appear in a future post. I’m probably lucky that the mini-storm moved through when it did, as the cool conditions likely calmed the beetles down and made them more willing subjects. By the time I finished photographing the second beetle, the sinking sun signaled a dinner bell, and I walked back to the campground super satisfied with how this visit had turned out.

After dinner, I turned the ultraviolet lights on despite the just-shy-of-full moon and customary coolish temperatures. I didn’t expect anything to show up, but you don’t know if you don’t try (nothing ever showed up!).

While waiting for nothing to come to the lights, I made several rounds of the large ponderosa pines, expanding the circuit to include some further toward the west end of the campground. As with the night before, I found a half dozen Zopherus uteanus crawling on the trunks (one was up too high to reach, though, and when I knocked it down with a stick it disappeared into the thick vegetation below the tree). I’d really like to know what these guys are up to during the day (hiding in the leaf litter at the base of the trees?) and what the larvae are doing (no idea!), but they certainly seem to be associated with pines (I’ve also collected Zopherus concolor at night on the trunks of Colorado pinyon pine). I also found a few more tenebrionid darkling beetles, including another Embaphion glabrum, crawling on the sandy ground beneath the trees. I expanded my search to include the trunks of some of the large Utah junipers, finding a few more tenebrionids on them.

With midnight approaching, I soaked in my last bit of experience at the place before retiring for the night and leaving the next morning.

Day 9

I left Ponderosa Grove Campground about 9:30 am with the plan to spend the next couple of days in Kyle Canyon and Lee Canyon northwest of Las Vegas. The drop down from the Colorado Plateau via the Virgin River Canyon was long the most spectacular stretches of freeway I’ve ever seen, but the sad reward waiting at the bottom was searing +100°F heat (the highest I saw registered on my car’s thermometer was 108°F!). Fortunately, turning off I-11 and heading west on Kyle Canyon Road gradually gained elevation. Before reaching the canyon proper, however, I had one of the trip’s top goals to take care of—setting a bottle trap for the recently described Acmaeodera raschkoi (recall that I encountered the namesake of this species, Mike Raschko, just two days prior at Ponderosa Grove Campground). I found the type locality no problem (where the modest gain in elevation had reduced the temperature to only 100°F!) and also found the trap that Mike had just set the day before we met.

I placed yellow bottle trap about 59 m to the west from Mike’s trap and a blue bottle trap about 45 m to the east. There was no reason to stay at the locality and try to collect, as things were super dry, the only green vegetation seen besides the Yucca jaegeriana (eastern Joshua tree—family Asparagaceae) dotting the landscape was a small Cylindropuntia ramosissima (branched pencil colla—family Cactaceae).

I had originally planned to camp lower down in the canyon at Kyle Canyon Campground, but by the time I got there it was already nearly filled to capacity. There were a couple of campsites still available, but the campground as a whole had a noisy, crowded vibe that wasn’t my cup of tea. I decided to take a chance and head further up the mountain to Hilltop Campground to see if I could find something more to my liking. It was a short drive up the mountain, and this campground also was nearly filled to capacity. However, it was a much quieter vibe, and among the three campsites still available was one that was isolated from all the others on the side of the mountain with spectacular views across the canyon and down into the desert below. Also, the 8300 ft of elevation offered much cooler conditions—a welcome change from the searing temperatures I had endured earlier in the day. It was perfect!

I quickly set up camp and began looking around. Not far from the campsite I found a wind-thrown branch Utah juniper, and slicing into the bark I found a dead adult Semanotus sp. prob. caseyi amplus (not as exciting as S. juniperi, but still a nice find) and a small scolytid bark beetle boring an oviposition gallery. I did a bit of chopping into the bark and found small new cerambycid galleries (probably either Callidium or Semanotus) and some very large frass-filled galleries at the larger end that may be Semanotus juniperi. I found the frass-plugged entrance hole to the sapwood —a sign that the beetle had not yet emerged—and chipped away on either side of the gallery into the sapwood until I saw the large cerambycid larvae sitting it it. This confirms that the wood is actively infested, and I’ll cut it up and bring it home for rearing. At the empty campsite next to mine, I found a small, recently dead Abies concolor (white fir—family Pinaceae), and closer inspection of the trunk revealed an adult Dicerca tenebrosa tenebrosa, and on a return trip to the tree I saw another one (but too high up to capture ☹️). I also hung a red wine-baited jug trap just south of the campsite. There wasn’t much else going on in the area and it was getting late, so I got dinner started.

I didn’t even consider setting up lights—the combination of a full moon and the cool, windy conditions that typify sites at this high of an elevation made the chance of success highly unlikely (in fact, it got so cool that I needed to pull on a fleece pullover). That did not, however, mean I could not do any night collecting—examining tree trunks has become a favorite strategy of mine that can be done on almost any night regardless of temperatures or wind. Trees under stress or recently dead (as well as recent wind throws or woodpiles) are especially good to look at, and I had noticed several during my earlier foray that I made a point to check. At the same time, I have also learned not to ignore living, seemingly healthy trees, as these can also harbor interesting beetles. Of course, the very first tree I headed for was the recently dead white fir on which I had collected Dicerca tenebrosa a few hours earlier, and I was rewarded right off the bat with an unusually small Zopherus uteanus. I wondered if this might be an interesting locality for the species, but I saw the species was recorded from Kyle Canyon in a review of the genus by Triplehorn (1972) (at which time it was still placed in the family Tenebrionidae). I quickly found another individual, this time on the trunk of a large Utah juniper—interestingly, the first non-pinaceous host on which I’ve found the species (although still a gymnosperm).

What I was most anxious to check, however, was a large Pinus monophylla (single-leaf pinyon pine) that I had seen nearby with a long, twisting scar from a lightning strike gashing down the trunk—surely there would be something on that (there wasn’t despite checking it repeatedly for the next couple of hours). What did produce beetles, though, was a large, recently wind-thrown branch from that very tree laying on the ground nearby—two species and multiple specimens of each, one (Oeme? sp.) searching frenetically back and forth along the branch, and the other (Haplidus? sp.) in the form of a mating pair. I found it interesting that my inspection of the branch earlier during the day produced nothing.

At this point, the night was already a reasonable success, but the greatest success lay just ahead. I had noticed a few large Utah junipers that showed evidence of infestation by Semanotus juniperi—or at least that what I presumed based on what I had learned about that species in the Kaibab Plateau a few days earlier. Not that I thought I would see adults of that species, but I figured the trees would have to be under some stress and might attract other beetles (I had already collected Z. uteanus off of one a few minutes prior). The first one I checked had nothing on it, but when I checked the second one I noticed a large black longhorned beetle on the trunk underneath some shredded bark. I carefully removed the overlying bark to get a better look at it and quickly realized that it was, indeed, S. juniperi! As I prepared to take a photograph, I noticed movement a bit higher on the trunk, and there sat a second individual! In the fraction of a second that followed, the memory of all the chainsaw work I had done a few days earlier in an effort to rear proper specimens flashed through my mind, yet here before me now were two live adults on their host in the wild. I presume the tree is attracting the adults and that there are already numerous individuals inside of it, as I found large swaths of larval galleries under the bark but no obvious adult emergence holes. The tree itself looks healthy and shows no outward sign of stress, and were it not for the evidence of larval galleries I wouldn’t have even suspected it was infested. As with Z. uteanus, this species also has been recorded from Kyle Canyon (Hammond & Williams 2013).

Over the next hour, I continued inspecting trees in the area, but especially those on which I’d found beetles, and eventually that effort was rewarded with a third S. juniperi on the same tree I collected the previous two. The final collection of the night occurred just after that, when I found not one but two more Z. uteanus, this time on the trunk of P. monophylla. I made one more quick round of the trees, but as it was now midnight I accepted the bounty of the night and turned in.

Days 10 & 11

Unfortunately, I had to end the trip rather abruptly due to a confluence of circumstances at home. The final straw was the rapid decline of Berlioz—our 20-year-old cat (only lifelong cat lovers will understand the bond between a man and his cat). It was not a surprise, and in the morning as soon as I was able to break camp, I left Kyle Canyon and spent the next two days blasting north on I-15 and west on I-70. Sadly, I wasn’t able to make it home before he passed. I’ve had many cats over the course of my life, but King Berlioz was the best!

©️ Ted C. MacRae 2025