Ask any astronomer when autumn begins, and they will likely tell you it begins at the autumnal equinox – when shortening days and lengthening nights become equal as the sun crosses over the celestial equator. According to them, fall began this year on September 22 – at 11:44:18 A.M. EDT, to be precise. I agree that autumn begins at a precise moment, but it is not at the equinox. Rather, it is that unpredictable moment when a sudden crispness in the air is felt, when the sky somehow seems bluer and shadows seem sharper, and hints of yellow – ever so subtle – start to appear in the landscape.

Ask any astronomer when autumn begins, and they will likely tell you it begins at the autumnal equinox – when shortening days and lengthening nights become equal as the sun crosses over the celestial equator. According to them, fall began this year on September 22 – at 11:44:18 A.M. EDT, to be precise. I agree that autumn begins at a precise moment, but it is not at the equinox. Rather, it is that unpredictable moment when a sudden crispness in the air is felt, when the sky somehow seems bluer and shadows seem sharper, and hints of yellow – ever so subtle – start to appear in the landscape.  In Missouri, with its middle latitudes, this usually happens a few weeks before the equinox, as August is waning into September. It is a moment that goes unnoticed by many, especially those whose lives and livelihoods have lost all connection with the natural world. To plants and animals, however, it is a clear signal – a signal to begin making preparations for the long cold months of winter that lie ahead. Plants that have not yet flowered begin to do so in earnest, while those that have shift energy reserves into developing seeds. Animals take advantage of their final opportunities to feed before enduring the scarcities of winter, digging in to sleep through them, or abandoning altogether and migrating to warmer climes. Insects begin hastily provisioning nests for their broods or laying eggs – tiny capsules of life that survive the harsh winter before hatching in spring and beginning the cycle anew.

In Missouri, with its middle latitudes, this usually happens a few weeks before the equinox, as August is waning into September. It is a moment that goes unnoticed by many, especially those whose lives and livelihoods have lost all connection with the natural world. To plants and animals, however, it is a clear signal – a signal to begin making preparations for the long cold months of winter that lie ahead. Plants that have not yet flowered begin to do so in earnest, while those that have shift energy reserves into developing seeds. Animals take advantage of their final opportunities to feed before enduring the scarcities of winter, digging in to sleep through them, or abandoning altogether and migrating to warmer climes. Insects begin hastily provisioning nests for their broods or laying eggs – tiny capsules of life that survive the harsh winter before hatching in spring and beginning the cycle anew.

Across much of Missouri, in the Ozark Highlands and in riparian ribbons dissecting the northern Plains, autumn brings an increasingly intense display of reds, purples, oranges, and yellows, as the leaves of deciduous hardwoods begin breaking down their chlorophyll to unmask underlying anthocyanins and other pigments.

Across much of Missouri, in the Ozark Highlands and in riparian ribbons dissecting the northern Plains, autumn brings an increasingly intense display of reds, purples, oranges, and yellows, as the leaves of deciduous hardwoods begin breaking down their chlorophyll to unmask underlying anthocyanins and other pigments.  In Missouri’s remnant prairies, seas of verdant green morph to muted shades of amber, tawny, and beige. This subtle transformation is even more spectacular in the critically imperiled sand prairies of the Southeast Lowlands, where stands of splitbeard bluestem (Andropogon ternaries – above) turn a rich russet color while fluffy, white seed heads (1st paragraph, 1st photo) appear along the length of each stem, evoking images of shooting fireworks. Small southern jointweed (Polygonella americana – right) finds a home at the northern extent of its distribution in these prairie remnants and in similar habitats in nearby Crowley’s Ridge, blooming in profusion once the cooler nights arrive. Butterfly pea (Clitoria mariana – 1st paragraph, 2nd photo) blooms add a gorgeous splash of soft purple in contrast to the muted colors of the plants around them.

In Missouri’s remnant prairies, seas of verdant green morph to muted shades of amber, tawny, and beige. This subtle transformation is even more spectacular in the critically imperiled sand prairies of the Southeast Lowlands, where stands of splitbeard bluestem (Andropogon ternaries – above) turn a rich russet color while fluffy, white seed heads (1st paragraph, 1st photo) appear along the length of each stem, evoking images of shooting fireworks. Small southern jointweed (Polygonella americana – right) finds a home at the northern extent of its distribution in these prairie remnants and in similar habitats in nearby Crowley’s Ridge, blooming in profusion once the cooler nights arrive. Butterfly pea (Clitoria mariana – 1st paragraph, 2nd photo) blooms add a gorgeous splash of soft purple in contrast to the muted colors of the plants around them.

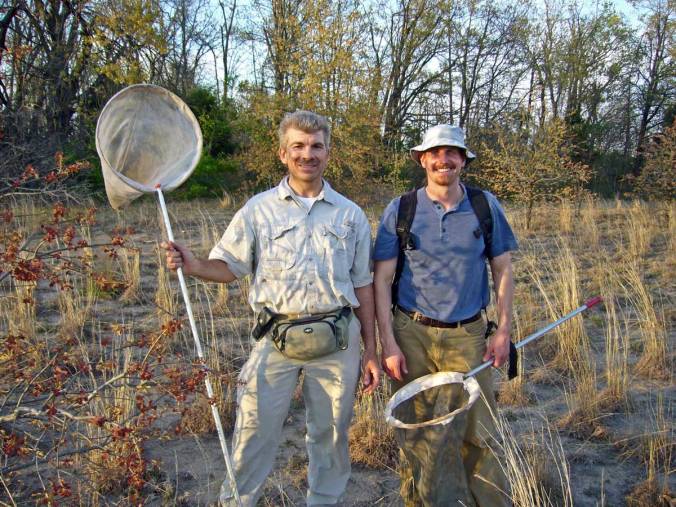

After first becoming acquainted with Missouri’s sand prairies this past summer, I knew a fall trip (or two) would be in order. The extensive deep, dry sand barrens were ideal habitat for sand-loving insects, including certain spring/fall species of tiger beetles that would not be active during the summer months. The cooler nights and crisp air of early fall make insect collecting extraordinarily pleasurable, so it took little effort to convince friends and colleagues Kent and Rich to join me on another excursion to these extraordinary remnant habitats, along with my (then 8 yr-old) daughter Madison (who would likely characterize this as “tallgrass” prairie).

After first becoming acquainted with Missouri’s sand prairies this past summer, I knew a fall trip (or two) would be in order. The extensive deep, dry sand barrens were ideal habitat for sand-loving insects, including certain spring/fall species of tiger beetles that would not be active during the summer months. The cooler nights and crisp air of early fall make insect collecting extraordinarily pleasurable, so it took little effort to convince friends and colleagues Kent and Rich to join me on another excursion to these extraordinary remnant habitats, along with my (then 8 yr-old) daughter Madison (who would likely characterize this as “tallgrass” prairie).  I was, as ever, on the lookout for tiger beetles; however, temperatures were cool, skies were overcast, and the fall season was just beginning, greatly limiting tiger beetle activity during this first fall visit. We did see one Cicindela formosa (big sand tiger beetle), which cooperated fully for a nice series of photographs. We also found single specimens of the annoyingly ubiquitous C. punctulata (punctured tiger beetle) and a curiously out-of-place C. duodecimguttata (12-spotted tiger beetle), which must have flown some distance from the nearest dark, muddy streambank that it surely prefers. Of greatest interest, we found two specimens of C. scutellaris (festive tiger beetle), which in this part of Missouri is represented by a population presenting a curious mix of influences from two different subspecies (more on this in a later post…). Despite the scarcity of tiger beetles, other insects were present in great diversity, some of which I share with you here.

I was, as ever, on the lookout for tiger beetles; however, temperatures were cool, skies were overcast, and the fall season was just beginning, greatly limiting tiger beetle activity during this first fall visit. We did see one Cicindela formosa (big sand tiger beetle), which cooperated fully for a nice series of photographs. We also found single specimens of the annoyingly ubiquitous C. punctulata (punctured tiger beetle) and a curiously out-of-place C. duodecimguttata (12-spotted tiger beetle), which must have flown some distance from the nearest dark, muddy streambank that it surely prefers. Of greatest interest, we found two specimens of C. scutellaris (festive tiger beetle), which in this part of Missouri is represented by a population presenting a curious mix of influences from two different subspecies (more on this in a later post…). Despite the scarcity of tiger beetles, other insects were present in great diversity, some of which I share with you here.

This bizarre creature, sitting on the stem of plains snakecotton (Froelichia floridana), is actually a neuropteran insect called an owlfly (family Ascalaphidae). Looking like a cross between a dragonfly and a butterfly due to its overly large eyes and many-veined wings but with long, clubbed antennae, this individual is demonstrating the cryptic resting posture they often assume with the abdomen projecting from the perch and resembling a twig. The divided eyes identify this individual as belonging to the genus Ululodes, and Dr. John D. Oswald (Texas A&M University) has kindly identified the species as U. macleayanus. As is true of many groups of insects, their taxonomy is far from completely understood. Larvae of these basal holometabolans are predaceous, lying on the ground with their large trap-jaws held wide open and often camouflaging themselves with sand and debris while waiting for prey. The slightest contact with the jaws springs them shut, and within a few minutes the prey is paralyzed and can be sucked dry at the larva’s leisure.

This bizarre creature, sitting on the stem of plains snakecotton (Froelichia floridana), is actually a neuropteran insect called an owlfly (family Ascalaphidae). Looking like a cross between a dragonfly and a butterfly due to its overly large eyes and many-veined wings but with long, clubbed antennae, this individual is demonstrating the cryptic resting posture they often assume with the abdomen projecting from the perch and resembling a twig. The divided eyes identify this individual as belonging to the genus Ululodes, and Dr. John D. Oswald (Texas A&M University) has kindly identified the species as U. macleayanus. As is true of many groups of insects, their taxonomy is far from completely understood. Larvae of these basal holometabolans are predaceous, lying on the ground with their large trap-jaws held wide open and often camouflaging themselves with sand and debris while waiting for prey. The slightest contact with the jaws springs them shut, and within a few minutes the prey is paralyzed and can be sucked dry at the larva’s leisure.

Another family of neuropteran insects closely related to owlflies are antlions (family Myrmeleontidae, sometimes misspelled “Myrmeleonidae”). This individual (resting lower down on the very same F. floridana stem) may be in the genus Myrmeleon, but my wanting expertise doesn’t allow a more conclusive identification [edit 4/12/09 – John D. Oswald has identified the species as Myrmeleon immaculatus]. Strictly speaking, the term “antlion” applies to the larval form of the members of this family, all of whom create pits in sandy soils to trap ants and other small insects, thus, it’s occurrence in the sand prairie is not surprising. Larvae lie in wait beneath the sand at the bottom of the pit, flipping sand on the hapless prey to prevent it from escaping until they can impale it with their large, sickle-shaped jaws, inject digestive enzymes that ‘pre-digest’ the prey’s tissues, and suck out the liquifying contents. Finding larvae is not easy – even when pits are located and dug up, the larvae lie motionless and are often covered with a layer of sand that makes them almost impossible to detect. I’ve tried digging up pits several times and have failed as yet to find one. Larvae are also sometimes referred to as “doodlebugs” in reference to the winding, spiralling trails that the larvae leave in the sand while searching for a good trap location – these trails look like someone has doodled in the sand.

Another family of neuropteran insects closely related to owlflies are antlions (family Myrmeleontidae, sometimes misspelled “Myrmeleonidae”). This individual (resting lower down on the very same F. floridana stem) may be in the genus Myrmeleon, but my wanting expertise doesn’t allow a more conclusive identification [edit 4/12/09 – John D. Oswald has identified the species as Myrmeleon immaculatus]. Strictly speaking, the term “antlion” applies to the larval form of the members of this family, all of whom create pits in sandy soils to trap ants and other small insects, thus, it’s occurrence in the sand prairie is not surprising. Larvae lie in wait beneath the sand at the bottom of the pit, flipping sand on the hapless prey to prevent it from escaping until they can impale it with their large, sickle-shaped jaws, inject digestive enzymes that ‘pre-digest’ the prey’s tissues, and suck out the liquifying contents. Finding larvae is not easy – even when pits are located and dug up, the larvae lie motionless and are often covered with a layer of sand that makes them almost impossible to detect. I’ve tried digging up pits several times and have failed as yet to find one. Larvae are also sometimes referred to as “doodlebugs” in reference to the winding, spiralling trails that the larvae leave in the sand while searching for a good trap location – these trails look like someone has doodled in the sand.

This digger wasp, Bembix americana (ID confirmed by Matthias Buck), was common on the barren sand exposures, where they dig burrows into the loose sand. Formerly included in the family Sphecidae (containing the better-known “cicada killer”), members of this group are now placed in their own family (Crabronidae). Adult females provision their nest with flies, which they catch and sting to paralyze before dragging it down into the burrow. As is common with the social hymenoptera such as bees and paper wasps, these solitary wasps engage in active parental care by providing greater number of prey as the larva grows. As many as twenty flies might be needed for a single larva. I found the burrows of these wasps at first difficult to distinguish from those created by adults of the tiger beetles I so desired, but eventually learned to distinguish them by their rounder shape and coarser, “pile” rather than “fanned” diggings (see this post for more on this subject).

This digger wasp, Bembix americana (ID confirmed by Matthias Buck), was common on the barren sand exposures, where they dig burrows into the loose sand. Formerly included in the family Sphecidae (containing the better-known “cicada killer”), members of this group are now placed in their own family (Crabronidae). Adult females provision their nest with flies, which they catch and sting to paralyze before dragging it down into the burrow. As is common with the social hymenoptera such as bees and paper wasps, these solitary wasps engage in active parental care by providing greater number of prey as the larva grows. As many as twenty flies might be needed for a single larva. I found the burrows of these wasps at first difficult to distinguish from those created by adults of the tiger beetles I so desired, but eventually learned to distinguish them by their rounder shape and coarser, “pile” rather than “fanned” diggings (see this post for more on this subject).

Robber flies (family Asilidae) are a favorite group of mine (or, at least, as favorite as a non-coleopteran group can be). This small species, Stichopogon trifasciatus (ID confirmed by Herschel Raney), was also common on the barren sandy surface. The specific epithet refers to the three bands of alternating light and dark bands on the abdomen. Many species in this family are broadly distributed but have fairly restrictive ecological requirements, resulting in rather localized occurrences within their distribution. Stichopogon trifasciatus occurs throughout North America and south into the Neotropics wherever barren, sandy or gravely areas near water can be found. Adults are deadly predators, swooping down on spiders, flies and other small insects and “stabbing” them with their stout beak.

Robber flies (family Asilidae) are a favorite group of mine (or, at least, as favorite as a non-coleopteran group can be). This small species, Stichopogon trifasciatus (ID confirmed by Herschel Raney), was also common on the barren sandy surface. The specific epithet refers to the three bands of alternating light and dark bands on the abdomen. Many species in this family are broadly distributed but have fairly restrictive ecological requirements, resulting in rather localized occurrences within their distribution. Stichopogon trifasciatus occurs throughout North America and south into the Neotropics wherever barren, sandy or gravely areas near water can be found. Adults are deadly predators, swooping down on spiders, flies and other small insects and “stabbing” them with their stout beak.

Prickly pear cactus (Opuntia humifusa) grows abundantly in the sandy soil amongst the clumps of bluestem, and on the pads were these nymphs of Chelinidea vittiger (cactus bug, family Coreidae). This wide-ranging species occurs across the U.S. and southward to northern Mexico wherever prickly pear hosts can be found. This species can either be considered a beneficial or a pest, depending upon perspective. On the one hand, it serves as a minor component in a pest complex that prevents prickly pear from aggressively overtaking rangelands in North America; however, prickly pear is used by ranchers as emergency forage, and fruits and spineless pads are also sometimes harvested for produce. In Missouri, O. humifusa is a non-aggressive component of glades, prairies, and sand and gravel washes, making C. vittiger an interesting member of the states natural diversity.

Prickly pear cactus (Opuntia humifusa) grows abundantly in the sandy soil amongst the clumps of bluestem, and on the pads were these nymphs of Chelinidea vittiger (cactus bug, family Coreidae). This wide-ranging species occurs across the U.S. and southward to northern Mexico wherever prickly pear hosts can be found. This species can either be considered a beneficial or a pest, depending upon perspective. On the one hand, it serves as a minor component in a pest complex that prevents prickly pear from aggressively overtaking rangelands in North America; however, prickly pear is used by ranchers as emergency forage, and fruits and spineless pads are also sometimes harvested for produce. In Missouri, O. humifusa is a non-aggressive component of glades, prairies, and sand and gravel washes, making C. vittiger an interesting member of the states natural diversity.

This wasp in the genus Ammophila (perhaps A. procera as suggested by Herschel Raney) was found clinging by its jaws to a bluestem stem in the cool morning, where it presumably spent the night. One of the true sphecid (or “thread-waist”) wasps, A. procera is a widespread and common species in eastern North America. One of the largest members of the genus, its distinctive, bold silver dashes on the thorax distinguish it from most other sympatric congeners. Similar to the habits of most other aculeate wasp groups, this species captures and paralyzes sawfly or lepidopteran caterpillars to serve as food for its developing brood. Females dig burrows and lay eggs on the paralyzed hosts with which the nests have been provisioned. Adults are also found commonly on flowers, presumably to feed on nectar and/or pollen.

This wasp in the genus Ammophila (perhaps A. procera as suggested by Herschel Raney) was found clinging by its jaws to a bluestem stem in the cool morning, where it presumably spent the night. One of the true sphecid (or “thread-waist”) wasps, A. procera is a widespread and common species in eastern North America. One of the largest members of the genus, its distinctive, bold silver dashes on the thorax distinguish it from most other sympatric congeners. Similar to the habits of most other aculeate wasp groups, this species captures and paralyzes sawfly or lepidopteran caterpillars to serve as food for its developing brood. Females dig burrows and lay eggs on the paralyzed hosts with which the nests have been provisioned. Adults are also found commonly on flowers, presumably to feed on nectar and/or pollen.

Rich is a bit of herpatologist, so when he brought this hog-nosed snake to our attention we all had a good time pestering it to try to get it to turn upside down and play dead. I had never seen a hog-nosed snake before but knew of its habit of rolling over and opening its mouth with its tongue hanging out when disturbed, even flopping right back over when turned rightside up or staying limp when picked up. We succeeded in getting it to emit its foul musky smell, but much to our disappointment it never did play dead, instead using its shovel-shaped snout to dig into the sand.

Rich is a bit of herpatologist, so when he brought this hog-nosed snake to our attention we all had a good time pestering it to try to get it to turn upside down and play dead. I had never seen a hog-nosed snake before but knew of its habit of rolling over and opening its mouth with its tongue hanging out when disturbed, even flopping right back over when turned rightside up or staying limp when picked up. We succeeded in getting it to emit its foul musky smell, but much to our disappointment it never did play dead, instead using its shovel-shaped snout to dig into the sand.  We had assumed this was the common and widespread eastern hog-nosed snake (Heterodon platirhinos); however, in our attempts to turn it over I noticed its black and orange checker patterned belly. I later learned this to be characteristic of the dusky hog-nosed snake (H. nasicus gloydi), only recently discovered in the sand prairies of southeast Missouri and regarded as critically imperiled in the state due to the near complete destruction of such habitats. Disjunct from the main population further west, its continued survival in Missouri depends upon the survival of these small sand prairie remnants in the Southeast Lowlands.

We had assumed this was the common and widespread eastern hog-nosed snake (Heterodon platirhinos); however, in our attempts to turn it over I noticed its black and orange checker patterned belly. I later learned this to be characteristic of the dusky hog-nosed snake (H. nasicus gloydi), only recently discovered in the sand prairies of southeast Missouri and regarded as critically imperiled in the state due to the near complete destruction of such habitats. Disjunct from the main population further west, its continued survival in Missouri depends upon the survival of these small sand prairie remnants in the Southeast Lowlands.