As Managing Editor of The Pan-Pacific Entomologist, I have the privilege of guiding manuscripts through the entire publication process—from submission and review through acceptance and preparation for final printing. It’s gratifying to see the results of a researcher’s efforts come to fruition, and it is also a good time to be an editor—due in no small part to the plethora of digital tools we have at our disposal. Knowing the amount of effort required to be an editor in today’s environment, I can’t imagine fulfilling the role in pre-computer days when manuscripts were prepared on a typewriter, submitted as hard copy, mailed to reviewers, collated upon their return (after interpreting hand-scribbled reviewer notations), and mailed back to authors for retyping. My heartiest congratulations to and respect for anyone who served as an editor in those days!

One of the holdovers from those days is the use of double-spaced text and numbered lines in draft manuscripts. This was necessary back then to provide space for reviewer comments and facilitate quick reference to specific portions of the manuscript. Of course, most journals today utilize fully electronic processes for submitting and reviewing manuscripts, and in some cases (including The Pan-Pacific Entomologist) a hard copy version of the manuscript may never be produced until the journal itself is issued. While the ability of reviewers to directly insert comments and suggested edits into an electronic version of the manuscript obviates the need to include line spacing and numbers, some authors still find themselves in the habit of preparing their manuscripts with such format. A bigger issue, however, brought on by the change from manual to electronic manuscript preparation is the temptation by some authors to overly “format” their manuscripts. Modern word processing programs (e.g., Microsoft Word) make it easier than ever to give documents visual appeal when printed, and most authors thus find themselves wanting to apply at least some formatting to their manuscripts. Indeed, some even go so far as to format their manuscript so that it closely resembles the printed journal! The problem is that most printers utilize file conversion software that automatically applies formatting according to a journal’s style sheet. Formatting commands used by word processing programs often interfere with those used by file conversion software, thus, to avoid conflicts any formatting applied to a draft manuscript must be stripped out prior to file conversion. The more of this that is done by the author prior to submission, the less potential for errors during printing. Unfortunately, just as secretaries don’t often make very good scientists, many scientists wouldn’t make good secretaries and find the prospect of “cleaning” an overly formatted manuscript more intimidating than it really is. Accordingly, I offer here this little “cheat sheet” for those who would like help in making sure their manuscript is clean prior to submission. These tips assume the use of Microsoft Word (since its file formats are acceptable for submission to The Pan-Pacific Entomologist), but a similar process should be possible with most other word processing programs.

Step 1. Select the entire document by pressing “Ctrl+A”.

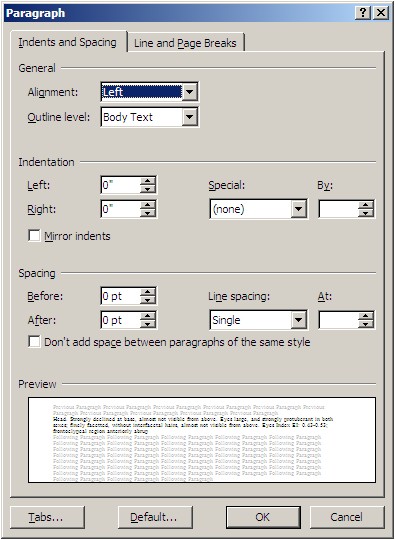

Step 2. Click on “Home” in the menu ribbon and open the “Paragraph” dialogue box.

Step 3. Click on the “Indents and Spacing” tab. Set all of the commands as shown in the figure below.

Step 4. Click on the “Line and Page Breaks” tab. Set all of the commands as shown in the figure below and click “OK”.

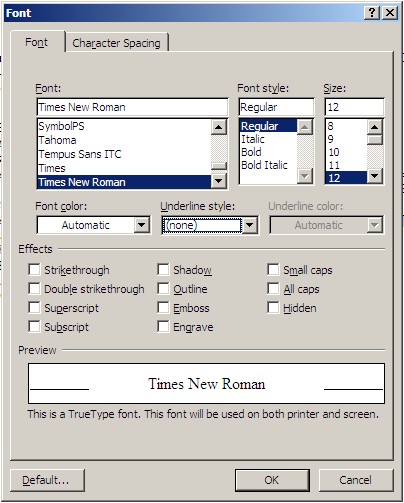

Step 5. Open the “Font” dialogue box (also under “Home” in the menu ribbon). Set all of the commands as shown in the figure below and click “OK”.

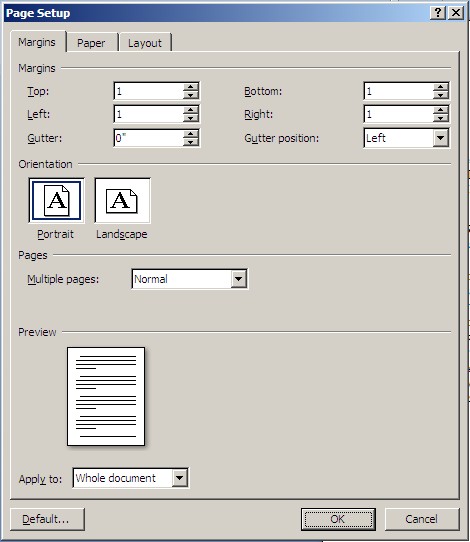

Step 6. Click on “Page Layout” in the menu ribbon and open the “Page Setup” dialogue box.

Step 7. Click on the “Margins” tab. Set all of the commands as shown in the figure below and click “OK”.

Voila! Your manuscript is free of all extraneous formatting commands and is ready for submission (assuming its contents are complete and well written). If there are portions of text that simply must be formatted (e.g., italics for scientific names) those can be reapplied. Of course, my best advice is to ensure the manuscript contains the above settings before it is even started. This not only ensures that formatting is limited to text that must be formatted, but also that the author will not need to spend additional time stripping out unneeded formatting during the preparation of final files for printing.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2012