Last fall I took my younger daughter to the Al Foster Trail on the western side of Castlewood State Park, just a few miles down the road from my house. As we walked the trail through typical bottomland forest next to the Meramec River, I noticed what appeared to be open ground on a rise to the north of the trail. When I went up to investigate, I saw a rare sight for Missouri—dry sand! Obviously a deposit from some past flood event, the post oaks established around its perimeter and native warm season grasses sparsely dotting its interior suggested it had been laid down many years ago. Such sights were likely common along the big river systems of pre-settlement Missouri, as natural flooding cycles laid sand deposits up and down the river courses, each deposit gradually succumbing to vegetation as new deposits were laid down elsewhere. Today, with channelization and levees for flood control, the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers are just narrow, hemmed-in shadows of their former selves, unable to lay down such deposits in most years until, at last, catastrophic flooding occurs on a grand scale (as is occurring now). Feeding into the Mississippi River just south of the Missouri River is the Meramec River—as the state’s only still-undamned undammed river system, it still has opportunity on occasion to lay down these interesting dry sand habitats.

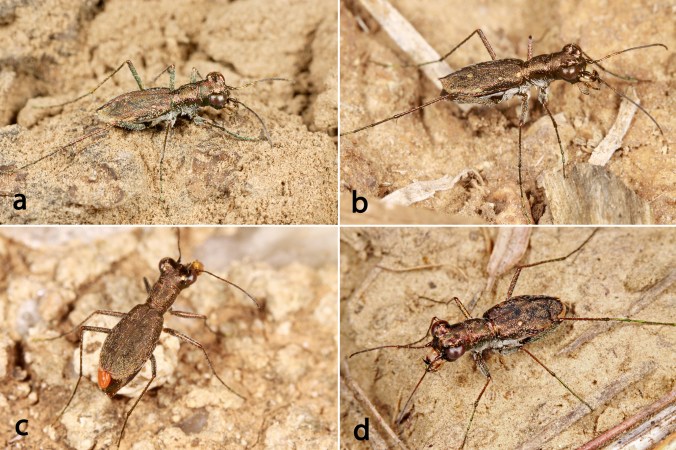

The dark brown coloration of this rather ''dirty'' individual is typical of most Missouri populations.

When I see dry sand habitats in Missouri, three tiger beetle species immediately come to mind—Cicindela formosa (big sand tiger beetle), C. scutellaris (festive tiger beetle), and Ellipsoptera lepida (ghost tiger beetle). My colleague and co-cicindelophile Chris Brown and I have spent many a weekend traveling up and down the state’s river systems with these species in mind. None of them are rare in the state, but their fidelity to deep, dry sand habitats also makes them by no means common. It is always cause for celebration when a new site is discovered for one of these species somewhere in Missouri. Thus, it was in anticipation of one (or more) of these species that I returned to the spot last week on the first truly gorgeous spring day of the season. Could it really be that, after ten years of searching for these species throughout the state, I would find a population just a few miles down the road from my house?!

A number of individuals in this population show traces of the bright coppery red coloration more typical of nominotypical populations west of Missouri.

Walking onto the site, I began to see tiger beetles immediately. However, they were Cicindela tranquebarica (oblique-lined tiger beetle), a common species in Missouri that enjoys not only dry sand habitats, but also wet sand, wet mud, dry clay, and even concrete habitats—hard to get excited about such a habitat slut! Nevertheless, within minutes I began seeing more robust beetles that were unmistakably big sand tigers. Big, bold, and beautiful, the beetles were wary in the late afternoon heat and quickly launched into their powerful escape flights that ended comically some 20 yards away with a characteristic bounce and a tumble. Such behavior might seem to make them impossible to photograph, but I’ve been at this for awhile and know their behavior pretty well—a slow, cautious approach, crouching carefully at the right distance, and crawling deliberately on elbows and knees while peering from behind the camera until it shows up in the lens set to 1:3 (one-third life size). Then it’s a matter of even more slowly closing the distance and scooting around to get the desired angles and composition. Move slowly enough and they’ll forget you’re there and resume normal behavior—you’ll be richly rewarded with views of foraging, stilting, and other classic tiger beetle behaviors.

Coloration and markings may seem conspicuous but provide excellent camouflage against the pebbley-sand substrate.

Most of the big sand tiger beetle populations we have found in Missouri are typical of the eastern subspecies C. formosa generosa, distinguished from other named subspecies by the dark brown dorsal coloration and thick white markings that are separate dorsally and joined along the outer edges of the elytra (Pearson et al. 2006). This subspecies is predominantly midwestern and northeastern in distribution, while the typically bright coppery-red individuals assigned to the nominotypical subspecies are found further west in the Great Plains. There are, however, certain populations in Missouri that show more or less suffusion of coppery-red coloration. This is typically explained as hybrid influence, as Missouri lies on the western edge of the distributional range of subspecies generosa. However, we have only seen these coppery-red indications on the eastern side of Missouri, while populations on the western side of the state along the Missouri River exhibit typical dark brown coloration. The population here in St. Louis Co. is the third population we have found to show this coppery-red influence, and in fact most of the individuals I saw exhibited greater or lesser amounts of this coloration. My personal belief is that there is no genetic basis for this subspecific distinction, but that the differences in color are instead related to conditions of the soil in which they live—possibly pH. Sand habitats in the eastern United States are typically acidic, while alkaline soils abound in the Great Plains (formerly a vast sea bottom). Hey, it’s a thought!

The combination of striking coloration and bold white markings exhibited by big sand tiger beetles might seem to make them quite conspicuous and vulnerable to predation—especially in the open, sparsely vegetated areas that they inhabit; however, against the textured sandy substrates on which they are found they are almost impossible to detect until they move. I’ve learned not to try to see them first and sneak up on them, as this is a lesson in futility. Rather, I simply walk through an area and fix my sights on individuals as they take flight, watching them as they fly and eventually land and then sneaking up to the spot where I saw them land. I generally need to stop about 8-12 feet out and study the spot carefully to pick them out, and then I can continue sneaking up on them.

Photo Details: Canon 50D w/ 100mm macro lens (ISO 160, 1/200 sec, f/16), Canon MT-24EX flash w/ DIY oversized concave diffuser. Typical post-processing (levels, minor cropping, unsharp mask).

REFERENCES:

Pearson, D. L., C. B. Knisley and C. J. Kazilek. 2006. A Field Guide to the Tiger Beetles of the United States and Canada. Oxford University Press, New York, 227 pp.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2011