Back in February, I learned that Mark Volkovitsh (Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Science, St. Petersburg) would be visiting Chuck Bellamy (California Department of Food and Agriculture) in Sacramento the very week that I was planning to be in Lake Tahoe. Chuck and Mark are two of the worlds leading specialists in Buprestidae, or jewel beetles, and have worked together on a number of projects dealing with the taxonomy and systematics of buprestid beetles. Mark, in particular, has focused on describing the larval forms of buprestids (“white wormy things,” as my wife calls them) and using larval morphology to supplement adult morphology in phylogenetic analyses. I’m not anywhere near being in their league in terms of authority in the family – a comparative dabbler, really – but for some reason they’ve both seen fit to accept me into the fraternity. I’ve been fortunate to spend time in the field with each of them, as well as visit them at their respective institutions. When I learned of Mark’s coincident visit, I couldn’t resist the chance to make the 2-hour drive from Lake Tahoe to Sacramento and spend the day with Mark and Chuck at the CDFA and discuss things buprestological. The wife and kids were fine with that, since her brother also lives in Sacramento, and it would be a chance for them to do some sight-seeing before we all got together for dinner. Upon arriving at CDFA, I also met Andy Cline, a nitidulid specialist at the CDFA (re-met actually, turns out we’d met some years back), and the four of us went out for an animated lunch at a nearby restaurant over some of the most delicious barbeque that I’ve ever tasted.

After lunch, I was most interested in discussing with Mark some buprestid larvae that I had collected in Big Bend, Texas in 2004. My colleague Chris Brown and I were hiking a low desert trail west of Rio Grande Village when we encountered a large, uprooted Goodding willow (Salix gooddingii) tree laying on the river bank. Wilting leaves were present on some of its branches, suggesting that the half-dead had been washed to its current location by the river during a recent flood. At the base of the trunk where the main roots projected, I noticed what appeared to be frass (the sawdust that wood boring beetle larvae eject after eating it – that’s right, grub poop!) under the edge of the bark at the live/dead wood interface. I used my knife to cut away some of the bark and immediately encountered a huge buprestid larvae. Its enormous size is matched only by a few desert southwest species: Polycesta deserticola, which breeds commonly in oak and is known from willow, but breeds only in dead, dry branches; and Gyascutus planicosta, whose larvae are restricted to the living roots of Atriplex and a few other asteraceous shrubs. Clearly, it could not be either of these species. The only other desert southwest buprestids large enough to produce a larva this large (~50 mm) are Lampetis drummondii and L. webbii. However, the larvae of both of these species are unknown, as is basic information regarding what hosts they utilize for larval development. Lampetis webbii is quite rare, but L. drummondii is, in fact, one of the most conspicuous and commonly encountered buprestid species in the desert southwest – that fact that its larva has remained unknown suggests that it utilizes living wood, probably feeding below the soil line. Thus, I immediately began to suspect that the larva might represent this species – a truly exciting development.

As I continued digging into the wood, I encountered a second, somewhat smaller larva in a neaby gallery, and further digging revealed another clue about its identity in the form of fragments of a dead adult beetle – all brilliant blue/green in color (identical to the color of L. drummondi), and the largest (the base of an elytron, or wing cover) showing the same pattern of punctation exhibited by L. drummondi adults. I placed the two larvae individually in vials with pieces of the host wood; however, I knew there was little chance that either larva, requiring living tissue upon which to feed, would complete its development once removed from its host gallery. They did survive for a time after my return to St. Louis, but when the largest larva became lethargic, I decided to go ahead and preserve them. I sent the photograph below (taken by Chris) of the living larvae to Mark, who confirmed that it did indeed appear to be a species of Lampetis, based on its large size and the narrowly V-shaped furcus on the pronotal shield (typical for members of the tribe to which Lampetis belongs).

Buprestid larva (prob. Lampetis drummondi) under bark of Salix gooddingii at trunk base - Big Bend National Park, Texas. Photo by Christopher R. Brown.

Considering the complete lack of published information on the larval biology of Lampetis drummondi and the several lines of evidence that these larvae, in fact, represent that species, it would be worthwhile to publish a description of the larva. However, formal description requires dissection, and I did not know how to do this. Mark, on the other hand, has dissected literally hundreds of buprestid larvae, including representatives of nearly every genus for which larvae are known. He is the buprestid larva expert, and what a thrill it was for me to learn how to do this from the Master himself, using the larger of these two probable Lampetis larvae as the subject. While we were dissecting the larva, we compared its features to those published for the European species Lampetis argentata (Danilevsky 1980) – the only member of the genus for which the larva is known – and confirmed their similarity and the larva’s likely close relationship to that species. Coincidentally, the larva of L. argentata develops in living roots of saxaul (Haloxylon) – a genus of large shrubs/small trees (family Amaranthaceae) that grows in the deserts of Central Asia. It thus appears that Lampetis species may, as a general rule, utilize living wood below the soil line for larval development, explaining why the larva of only one (now two) of the nearly 300 species in the genus worldwide has been found.

REFERENCES:

Danilevsky, M. L. 1980. Opisanie zlatki Lapmetis [sic] argentata (Coleoptera, Buprestidae) – vreditelya saksaula [Description of the larva of Lapmetis [sic] argentata (Coleoptera, Buprestidae) – the pest of Haloxylon. Zoologicheskii Zhurnal 59:791–793.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2010

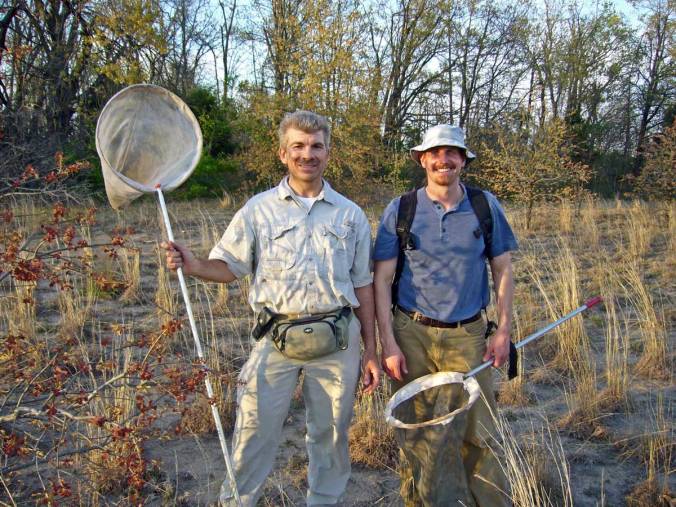

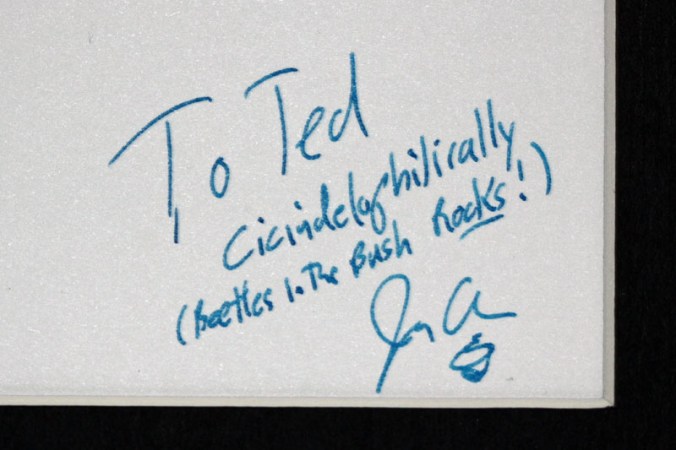

Those of you who have followed this blog for any length of time have likely noticed fairly regular participation in the comments sections by one James C. Trager. Occasionally irreverent and always articulate, his informed quips are among those that I have enjoyed the most. One can surmise from James’ comments that he knows a thing or two about entomology himself, but to say this would be an understatement! Like me, James is a passionate entomologist whose scientific interests take him deep into many related fields of natural history study. Unlike me, James is a formally trained insect taxonomist, specializing in ants (family Formicidae). He has conducted numerous biogeographical and systematic studies on this group, much of it in the southeastern U.S. (list of

Those of you who have followed this blog for any length of time have likely noticed fairly regular participation in the comments sections by one James C. Trager. Occasionally irreverent and always articulate, his informed quips are among those that I have enjoyed the most. One can surmise from James’ comments that he knows a thing or two about entomology himself, but to say this would be an understatement! Like me, James is a passionate entomologist whose scientific interests take him deep into many related fields of natural history study. Unlike me, James is a formally trained insect taxonomist, specializing in ants (family Formicidae). He has conducted numerous biogeographical and systematic studies on this group, much of it in the southeastern U.S. (list of