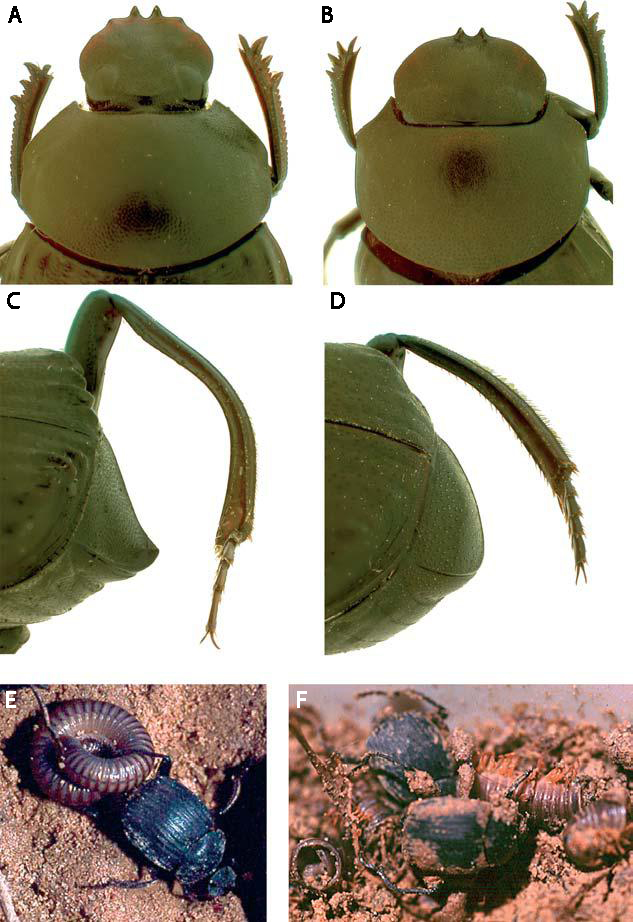

In my recent summary of the latest issue of the journal Cicindela, I included a scan of the cover of that issue and its stunning image of the 3rd-instar larva of Megacephala megacephala¹ from Africa. This otherwordly-looking, four-eyed beast was photographed with jaws agape at the entrance to its burrow in Guinea Bissau by Dr. Artur M. Serrano (University of Lisbon, Portugal). I was grateful for his permission to post a scan of this spectacular image; however, he did even better and sent me high-resolution images of not only the larva (above) but the adult (below) as well. This species is one of 13 assigned to the genus—presently restricted to Africa (though not always, see discussion below), where they are usually found in savanna-type habitats and are active during the crepuscular and nocturnal periods (Werner 2000).

¹ An example of a tautonym, i.e. a scientific binomen in which the genus and species names are identical. Familiar tautonymic binomina include the gorilla (Gorilla gorilla), green iguana (Iguana iguana), and European toad (Bufo bufo). Tautonyms are expressly prohibited in plant nomenclature (see Article 23.4 of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature) but are permitted and, in fact, quite common in zoological nomenclature; Wikipedia lists 51 mammals, 82 birds, 15 reptiles & amphibians, 54 fish, and 33 invertebrates (though not Megacephala megacephla!).

For those of you who see a strong resemblance by this species to another tiger beetle I featured recently, Tetracha floridana (Florida Metallic Tiger Beetle), this is not merely a coincidence. Megacephala and Tetracha are quite closely related, and in fact the two genera, along with a handful of other closely related genera, are at the center of one of the longest-standing disputes in tiger beetle taxonomy (Huber 1994). The genus Megacephala was established by Latreille (1802) for the species pictured here (originally described as Cicindela megacephala Olivier). As additional taxa were found in Africa, Australia and the Western Hemisphere and assigned to Megacephala, several workers attempted to divide the genus into multiple genera (with New World taxa being assigned to Tetracha and a few other mostly South American genera); however, there was little agreement on how these genera should be defined and on what characters they should be based. The debate was effectively swept under the rug in the early 20th Century when Walter Horn, one of the most influential cicindelophiles of all time, accepted a monotypic Aniara based on the strange South American species A. sepulcralis but reunited the world’s remaining taxa within the single genus Megacephala in his world catalogue (Horn 1910). Horn’s use of Megacephala as a catch-all genus was followed by subsequent workers for almost a full century until Huber (1994) once again proposed restricting Megacephala to certain of the African species and resurrecting the genus Tetracha for the bulk of the New World fauna. He also urged additional analyses to resolve the status of the remaining generic names and their composition, which subsequently saw increasing use as subgenera of Megacephala² and later as genera.

² Thus, as type-species for the genus, the species featured here became known as Megacephala (Megacephala) megacephala (Werner 2000)—a triple tautonym that translates to the “Big-headed, Big-Headed, Big-Headed” tiger beetle! Perhaps it’s best that I’m not an African tiger beetle specialist; I probably would have been unable to resist the temptation to resurrect M. senegalensis and assign it as a subspecies of M. megacephala, just so I could refer to the nominate form as Megacephala (Megacephala) megacephala megacephala!

The reversal of Horn’s concepts now appears to be complete, with all seven former subgenera of Megacephala formally being accorded full generic status (Naviaux 2007). This classification is strongly supported by molecular analysis of nuclear 18S and mitochondrial 16S and cytochrome oxidase gene sequences (Zerm et al. 2007), with the resulting dendrogram indicating three monophyletic clades corresponding to the African/Palearctic (Megacephala and Grammognatha, respectively), Western Hemisphere (Aniara, Metriocheila, Phaeoxantha and Tetracha) and Australian (Australicapitona and Pseudotetracha) genera³. The African/Palearctic clade was found to occupy a basal position in the tree, while the Western Hemisphere and Australian clades were more derived. These data support the hypothesis that the early evolution of the megacephalines took place during the break-up of the ancient Gondwana megacontinent, which began about 167 million years ago (middle Jurassic period) and sequentially disconnected Africa from South America and Australia.

³ One striking deviation from the current classification, however, was the support for nesting the single Aniara species within Tetracha, a placement that renders Tetracha paraphyletic and, thus, requires either its division into multiple genera or the sinking of Aniara as a distinct genus. The support for this placement was quite strong and mirrored the results of a broader molecular phylogenetic study of tiger beetles based on full-length 18s RNA data (Galian et al. 2002). The authors concede that this puzzling placement is not corroborated by numerous morphological, ecological and ethological characters that distinguish Aniara from all known Tetracha species.

REFERENCES

Galián J., J. E. Hogan and A. P. Vogler. 2002. The origin of multiple sex chromosomes in tiger beetles. Molecular Biology and Evolution 19:1792–1796.

Horn, W. 1910. Coleoptera Adephaga, Fam. Carabidae, Subfam. Cicindelinae. In P. Wytsman (editor). Genera Insectorum. Fascicle 82a. Desmet-Vereneuil, Brussels, Belgium, pp. 105–208.

Huber, R. L. 1994. A new species of Tetracha from the west coast of Venezuela, with comments on genus-level nomenclature (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Cicindela 26(3/4):49–75.

Latreille, P. A. 1802. Histoire Naturelle, Générale et Particulière des Crustacés et des Insectes. Paris: F. Dufart 3 xii 13 + 467 pp.

Naviaux R. 2007. Tetracha (Coleoptera, Cicindelidae, Megacephalina): Revision du genre et descriptions de nouveaus taxons. Mémoires de la Société entomologique de France 7:1–197.

Werner, K. 2000. The Tiger Beetles of Africa (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Volume 1. Taita Publishers, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic, 191 pp., 745 figures.

Zerm, M., J. Wiesner, J. Ledezma, D. Brzoska, U. Drechsel, A. C. Cicchino, J. P. Rodríguez, L. Martinsen, J. Adis and L. Bachmann. 2007. Molecular phylogeny of Megacephalina Horn 1910 tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment 42(3):211–219.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2009