Welcome to the 16th “Collecting Trip iReport” covering this season’s third—and final—insect collecting trip to eastern and southern New Mexico. This trip occurred during September 9–18, following “Act 2” on June 17–28 and “Act 1” on May 14–25, and had the objective of retrieving 18 “jug traps” and six “bottle” traps placed on the first trip. Unlike the previous two trips, I traveled solo this time, but I still managed to visit 16 different localities—14 in New Mexico, one in Oklahoma, and one in Kansas.

Per usual, this report assembles field notes largely as they were generated during the trip. They have been lightly “polished” but not substantially modified based on subsequent examination of collected specimens unless expressly indicated by “[Edit…]” in square brackets. Unlike my previous two trips this season, I did bring my “big” camera and took lots of macro photographs of insects in the field—these will be featured in future individual posts. However, as always, this “iReport” features iPhone photographs exclusively. Previous iReports in this series are:

– 2013 Oklahoma

– 2013 Great Basin

– 2014 Great Plains

– 2015 Texas

– 2018 New Mexico/Texas

– 2018 Arizona

– 2019 Arkansas/Oklahoma

– 2019 Arizona/California

– 2021 West Texas

– 2021 Southwestern U.S.

– 2022 Oklahoma

– 2022 Southwestern U.S.

– 2023 Southwestern U.S.

– 2024 New Mexico: Act 1

– 2024 New Mexico: Act 2

Day 1

3.2 mi SSW of Piqua

Woodson County, Kansas

On my way to Black Mesa State Park (in the northwestern corner of Oklahoma) where I will be spending the night, I stopped at this abandoned quarry at the suggestion of Dan Heffern, who grew up in the area and collected his first Megacyllene decora (amorpha borer) here as a teenager on the Amorpha fruticosa that grows commonly on the steep banks surrounding the now water-filled reservoir.

The timing seemed right, as patches of goldenrod (Solidago sp.) surrounding the reservoir were also just coming into bloom, but no adults were seen on either the stems of amorpha or the flowers of goldenrod. I did get to see a garter snake try (and fail) to catch a leopard frog. The snake had hold of the frog by one of its hind legs, but the frog used its other hind leg to eventually free himself while peeping desperately. I was kind of rooting for the frog, even though it would have been interesting to watch the snake as it ingested its prey.

I was hoping to make it to Black Mesa State Park (at the far western end of the Oklahoma panhandle) before dark, but the sun setting on a lonely stretch of highway well beforehand told me that wouldn’t be possible.

Black Mesa State Park

West Canyon Campground

Cimarron County, Oklahoma

I arrived at the park well after sunset, but the tent went up quickly and I found a Cicindelidia punctulata (punctured tiger beetle) on the exposed clay after I finished.

This prompted me to put the headlamp on and walk the roads to look for beetles. Amblycheila cylindriformis (Great Plains giant tiger beetle) has been taken in the park, though in July (September is likely a bit too late). Nevertheless, I walked to the spot where it had been found about a mile up the road, scanning the road with my headlamp as I walked.

A few big black Eleodes darkling beetles gave me the occasional false start, but in the end I did not find the tiger beetle. I did, however, get to see a beautiful 1st-quarter moonset amidst light high clouds and a starry starry night.

Day 2

0.1 mi S Hwy 325 on D0035 Rd

Cimarron County, Oklahoma

There is an iNat record of an Amblycheila cylindriformis (Great Plains giant tiger beetle) larval burrow at this spot. Even though the record is a couple of years old, I thought I’d stop by and see if I could find one for myself. I did, fairly quickly I might add, right along the top edge of the steeply-sloped clay embankment alongside the road.

A bit more searching nearby revealed the carcass of an adult embedded in the clay slope—I dug it out (in pieces) and saw the abdomen covered with a bit of spider webbing. I’m still not sure how it came to be embedded within the clay with only the head and probotum exposed.

Mills Rim Campground

Kiowa National Grassland

Harding County, New Mexico

It took a couple of hours of driving to get to this, the first of six trap locations I have in New Mexico. I was happy to see all three jug traps still hanging, intact, and full of catch. All three had lots of Euphoria (mostly fulgida) and a fair number of elaterids, but other than a single Tragosoma sp. (I haven’t collected one of these in many years!) in the SRW trap the cerambycids seemed limited to just a few elaphidiines. The bottle trap had lots of bees (for Mike) and Euphoria kerni, but I did see a few Acmaeodera spp. and—remarkably—another Tragosoma sp. (an unusual catch for a bottle trap!).

While I was checking the traps, I kept an eye out for tiger beetles and flower-visiting longhorns and buprestids. I did see one Acmaeodera rubronotata on flowers of Gutierrezia sarothroides (broom snakeweed), but this was the only one despite looking at many flowers and I chose not to linger.

“San Jon Hill”

9.3 mi S of San Jon

Quay County, New Mexico

Another two-hour drive brought me to “San Jon Hill”—a sandstone escarpment at the edge of a plateau featuring juniper/oak/pinyon woodland. Again, all three of my jug traps were still hanging and intact, and the SRW and SRW/EtOH traps were full of beetles! The EtOH trap, on the other hand, was bone-dry with far fewer specimens. Like Mills Rim, Euphoria (again, mostly fulgida) were dominant, but I was elated to see multiple Enaphalodes hispicornis (a species I’ve never collected) along with a few E. atomarius in all the traps. The SRW/EtOH and EtOH traps also had several Aethecerinus wilsonii—a great find that I first got near Kenton last year. There was also a Stenaspis solitaria in the EtOH trap along with the expected smattering of elaphidiines and elaterids in all three traps. The bottle trap also was overwhelmed, primarily with bees (for Mike), but I did see a fair number of Acmaeodera spp. (I’m hoping this includes A. robigo, one of which was in this trap last time).

Otherwise, I saw little insect activity despite the abundance of plants in flower—a Eusattus reticulatus (sand darkling beetle) crawling on the ground being my only other capture.

Continuing further south towards Oasis State Park, there is a field of wind turbines that, on my previous passing, provided a picturesque scene. This time again provided such opportunity.

Oasis State Park

Roosevelt County, New Mexico

The drive from my last stop was supposed to be only 1½ hours, but having to reroute after sitting a while for a motionless train and an unexpected but welcome FaceTime call with my grandson conspired to delay my arrival at the park until well after darkness had settled. No problem—I’ve set up many a tent in the dark, and the burger cooked on the grill afterwards was no less tasty. (I also had sufficient reception to relish watching Kamala Harris clean TFG’s clock, which was followed “Swiftly” by a major endorsement and only served to further buoy my mood.) After the evening’s entertainment, I set out to check a couple of light sources in the park to see if they’d attracted any beetles—a small utility building near the RV campground, and a mercury-vapor streetlight closer to the tent campground. Tenebrionids abounded in number and diversity under both light sources, and I took from each several examples of the weirdly-explanate Embaphion muricatum.

Scarabs were limited mostly to small melolonthine, but I did pick up nice series of at least two species of bolboceratine geotrupids.

I had hoped to encounter the sand dune endemic longhorned beetle, Prionus spinipennis (I don’t know if it actually occurs here), but on my last visit in June I encountered its early-season counterpart P. arenarius. None were seen, however, so I am hopeful that I find it further south at Mescalero Sands, where it is known to occur and where I plan to go in the next couple of days.

Day 3

Passing through Portales in the morning, I did a double-take as I passed this “low rider.” I circled around the block so I could get another look, and for the rest of the day I had the eponymous song from Cheech & Chong’s Up In Smoke as a brain-worm.

Portales Recreation Complex

Roosevelt County, New Mexico

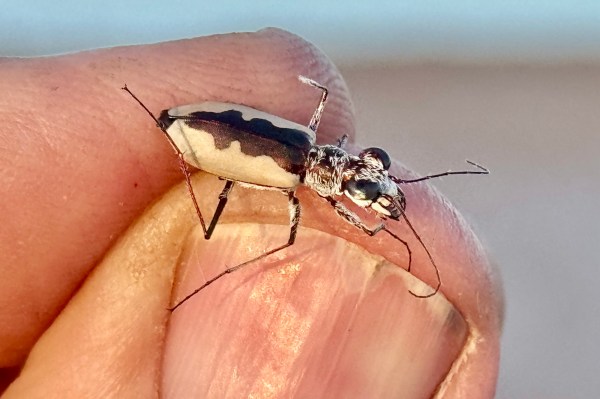

My first stop for the day turned out to feature little-disturbed (i.e., ungrazed) dry grassland surrounding the ballfields. There are some iNat records of a couple of fall-occurring longhorned beetles (Megacyllene angulifera, Tragidion coquus) from here, so I thought I’d try my luck as I head south towards Mescalero Sands. The season felt a little early, as even though there were plenty of Helianthus annuus (annual sunflower) in bloom, the Gutierrezia sarothrae (broom snakeweed) was not. Still, I checked the sunflowers but saw only Chauliognathus basalis (Colorado soldier beetles) in abundance. The visit was “not for naught,” however—walking the sandy loam 2-track through the lower west side I encountered three species of tiger beetles: Jundlandia lemniscata rebaptisata (rouged tiger beetle), Cicindelidia punctulata chihuahuae (Chihuahua punctured tiger beetle), and—my favorite—Cicindelidia obsoleta obsoleta (large grassland tiger beetle).

“Mydas Alley”

6.6–6.9 mi S of Floyd

Roosevelt County, New Mexico

There are some iNat records of several interesting tiger beetles at this spot—an endless dry grassland with a sandy/red clay 2-track cutting through it. These include Cicindela formosa rutilovirescens (Mescalero Sands tiger beetle)—a main target for the trip, Cicindelidia obsoleta obsoleta (large grassland tiger beetle), and Cicindelidia nigrocoerulea (black sky tiger beetle).

I didn’t have much expectation for the latter, since the record is based on a single, dead individual, and I’d just found C. o. obsoleta at the previous site closer to Portales, but I was really hoping to find C. f. rutilovirescens. Almost immediately I caught what I thought could be C. nigrocoerulea on the sandy/red clay 2-track near where I parked; however, it turned out to be the similar Cicindelidia punctulata chihuahuae (Chihuahua punctured tiger beetle), distinguishable by the single seta on the basal antennomere instead of two (an eyeglass on a lanyard around the neck at all times can really come in handy), its subparallel elytra that are slight wider posteriorly rather than subarcuate, and the generally shinier rather than opaque surface of its elytra.

I found more C. punctulata further down the 2-track (although they looked more like the nominotypical subspecies due to their dark brown rather than greenish coloration), and I found myself paying attention to almost every C. punctulata that I encountered hoping one might be C. nigrocoerulea. Sadly, none would prove to be the latter (at least based on my examination in the field—subsequent closer examination at home may prove otherwise). I did, however, encounter a single Cicindela scutellaris scutellaris (festive tiger beetle) to add another tiger beetle species to the trip list.

At the far end of the 2-track, I noticed something sitting on the stem of Eriogonum annuus (annual buckwheat) and was delighted to see it was Crossideus discoideus—one of the genera of fall-active longhorned beetles that I was hoping to encounter on the trip.

A bit of careful searching in the immediate vicinity revealed more individuals on the stems and flowers of the plants growing in the area, and on the way back I found another C. discoideus on the spent flower of Heterotheca subaxillaris (camphorweed) near the front part of the 2-track. I had not, however, seen my main objective—C. f. rutilovirescens—and was beginning to resign myself to getting skunked on the species. As I reached the car and turned to go briefly down the 2-track to the east, however, I saw one on the more wide open section of the 2-track, then quickly saw another! Those would be the only two I would see until I turned back and approached the car again, seeing the third and final individual of the stop.

I was hoping to get field photos with the “big” camera, but their scarcity made me decide to wait for my next chance at Mescalero Sands, where I hope to find them as well. The number of tiger beetle species seen on the trip now stands at six (if I include the Amblycheila cylindriformis carcass seen yesterday in the Oklahoma panhandle).

Presler Lake

Chaves County, New Mexico

Over the past couple of years, I have begun to rely ever more heavily on the natural history platform iNaturalist as a source for finding promising localities for interesting species. The first two localities I visited today were both found prior to my departure on this trip while searching for localities where species of Buprestidae, Cerambycidae, and Cicindelidae have been recorded. This locality was not found before I left, but rather after I left the last spot and saw that several species of beetles, including Eunota togata globicollis (alkali tiger beetle), had been reported from the area around this alkaline lake.

As I walked toward the lake, I noticed lots of Isocoma pluriflora (southern goldenbush), normally a good host for Crossidius longhorned beetles, that was already past bloom and wondered if any Crossidius would still be found on them. As I reached the lake margin, I saw a Crossidius suturalis male, but it was instead perched on Atriplex canescens (four-winged saltbush). No sooner than after I had photographed the beetle, marked its location, and made an entry in my notes, I noticed another—this one a big female perched on the spent bloom of I. pluriflora.

The locality where E. t. globicollis had been recorded was on the far west side of the lake, so I walked the lake margin in that direction while checking the saltbush and goldenbush along the way. It was quite a while before I found another C. suturalis on I. pluriflora, and on another plant very nearby I found a nice little cetoniine scarab: Euphoria pilipennis—a species I’ve never collected before.

The walking and checking was eating up time, however, and I noticed that the sun was beginning to dip rather low in the western sky. I needed to focus on finding E. t. globicollis if I wanted to get back to the car before it got dark (I would still have another hour’s drive to get to my campground near Roswell). I’d walked towards the lake margin earlier, going as far as I could go toward the water before my shoes started sinking into the thick, alkaline-encrusted mud, and didn’t see any tiger beetles, so I was not really expecting to see the species (it had been recorded there during the height of the summer). Remarkably, right as I made my closest approach to the spot, I saw one—E. t. globicollis running on the wet mud near the water’s edge of the alkaline lake.

I walked the margin all the way back to where I needed to divert back to the car and saw several more individual, but I was unsuccessful in capturing any beyond the first one!

As I neared the car and the sun sank behind the horizon, I assumed the day’s collecting was done. Just then, I noticed a Gyascutus sp. sitting on Atriplex canescens (based on location, I suspect it is G. planicosta obliteratus), and within a few steps from there I saw another C. suturalis on I. pluriflora. This prompted some additional looking in the area around the car, but eventually the light became too dim to allow effective searching. It was an impromptu stop at an unlikely location and ended up being a successful stop for the trip.

Day 4

Palmer Lake Campground

Bottomless Lakes State Park

Chaves County, New Mexico

I arrived at my favorite campsite in this campground well after dark last night, so I was pleased to see the area as green as could ever be imagined when I awoke this morning. Copious blooms of Allionia incarnata (trailing four o’clock) and Kallstroemia parviflora (small-flowered carpetweed) were blanketing the adjacent gypsum/red siltstone slopes.

Not much of note was seen on the blooms, but I did find the fascinatingly-inflated Cysteodemus wislizeni (black bladder-bodied blister beetle) crawling on the ground amongst them.

A quick walk up into the draw behind the campsite also revealed little besides a variety of darkling beetles (family Tenebrionidae)—some of them monstrously-sized. However, once back at the campsite I found a rather beat up right elytron of what I believe to be Amblycheila picolominii (plateau giant tiger beetle). Since I included A. cylindriformis (Great Plains giant tiger beetle) to my running list of tiger beetle species seen on the trip, I’ll add this one as well as #8.

Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge

Chaves County, New Mexico

I found another iNaturalist record of Cicindelidia nigrocoerulea (black sky tiger beetle) at this refuge, which is located just north of Bottomless Lakes. I didn’t find this species at the previous spot where I looked for it (as far as I know), and since the refuge is managed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, I can only “look but don’t touch” (no collecting permit). Because of this, I decided to make today a “big camera” day instead of an “insect net” day.

Tiger beetles were scarce on the dry alkaline flats where the record was taken (albeit, many years ago and in July) and limited to the über-common Eunota circumpicta johnsonii (Johnson’s tiger beetle) and Eunota togata globicollis (alkali tiger beetle). I’ve photographed both of these species already but attempted a few shots of each anyway to get some practice (photographing tiger beetles is challenging at best, requiring patience, persistence, and a willingness to get down on the ground no matter how dirty you will get). I found it difficult to approach either species (but especially the latter) in what was by then the heat-of-the-day, and the only shots I managed were of two individuals (one of each species)—engaged in shade-seeking behavior. I did find the mostly complete skeleton of what I take to be a common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina).

The margins of the oxbow lake on the other side of the parking lot were much wetter, and accordingly the tiger beetles were much more abundant there as well. In addition to the aforementioned E. c. johnsonii, which here also was by far the most abundant species, I observed Cicindelidia ocellata ocellata (ocellated tiger beetle)—common throughout the southwest, and Cicindelidia tenuisignata (thin-lined tiger beetle)—much less commonly encountered and a species I’d first seen during my previous trip to Bottomless Lakes in June. I managed to photograph a mating pair of E. c. johnsonii, but try as I might I was unable to photograph C. o. ocellata or C. tenuisignata—a rather deflating failure for someone who prides himself in his tiger beetle photography skills. For now, the iPhone photos that I took last time of individuals of the latter species attracted to ultraviolet light at night will have to do. There was a good amount of Isocoma pluriflora (southern goldenbush) still in good bloom around the parking lot, and I managed to photograph a fine male Crossidius suturalis suturalis on the flowers.

Palmer Lake Campground

Bottomless Lakes State Park

Chaves County, New Mexico

The day’s high heat not only made futile any further attempts to photograph tiger beetles at Bitter Lake, but gave me pause about going out for more collecting as soon as I returned to my campsite—I needed a bit of time to chill. Eventually, however, I worked up the motivation to strap on the pack and grab the net. I had earlier noticed a nice stand of Isocoma pluriflora (southern goldenweed)—a good host for Crossidius longhorned beetles—at the end of the campground road, and that became my first destination. It took a bit of time before I found C. s. suturalis on the flowers, but after working the stand for about an hour I had a nice handful.

Many other insects were also visiting the flowers, most visibly a large Pepsis tarantula hawk (prob. P. grossa)—which I could not photograph—and numerous colorful blister beetles that I take to be Pyrota concinna—which I did photograph.

I next visited the small, slightly elevated picnic area next to the campground, where last time I had collected a small series of a nice, large buprestid, Gyascutus planicosta obliteratus, on Atriplex canescens (four-winged saltbush). I saw one yesterday at Presler Lake, and I hoped they might be still hanging around here as well, but no dice. I did, however, notice a small beetle clinging onto the foliage of Neltuma glandulosa (honey mesquite, formerly Prosopis glandulosa), which turned out to be a very late-occurring Acmaeodera mixta. I noticed that the temps were suddenly getting milder, signaling the onset of evening and reminding me to head back to camp since I wanted to drive to Mescalero Sands (about 40 miles away) for some evening/night collecting.

Mescalero Sands Recreation Area

Chaves County, New Mexico

There are two species of Prionus longhorned beetles endemic to the sand dunes of southeastern New Mexico and western Texas—P. arenarius, which occurs during spring and early summer, and P. spinipennis, which occurs during late summer and fall. I’ve collected the former twice—once several years ago here at this very spot, and again this year at Oasis State Park back in June. I’ve never collected P. spinipennis, however, and figured they should be out by now. I had brought with me a few prionic acid lures, to which the males are attracted (prionic acid is a main component of the pheromones that females of all Prionus species release to call mates), and I also hoped to find and photograph the sand dune subspecies of Cicindela formosa—i.e., C. f. rutilovirescens (which I found yesterday near Portales but did not photograph). Unfortunately, my arrival just 20 minutes before sunset precluded the latter possibility, so instead I hiked into the dunes a short distance to place the pheromone lures and enjoyed a spectacular sunset and moonrise, with the sky morphing from blue to orange before finally turning black.

As soon as darkness fell, I began scanning the sand for anything crawling. Darkling beetles (family Tenebrionidae) appeared in numbers and diversity—my favorites, as always, being the weirdly-explanate Embaphion muricatum, which were as common as I’ve ever seen them.

A sand dune endemic Jerusalem cricket, Ammopelmatus mescaleroensis (Mescalero Jerusalem cricket), some of them being quite large, was also quite common.

About an hour after sunset, I finally saw one—a male P. spinipennis walking urgently across the sand in the general direction of the pheromone lure. I was glad my hunch had paid off and waited to see when the next male would arrive.

Sadly, I waited and waited—expectantly walking the dunes in the area around the vicinity of the lure looking for the next one, but it never came. Perhaps I am a bit on the early side of their adult activity period. Nevertheless, one is better than none, and it gives me a reason to look forward to returning to the dunes some other time during the heart of the fall season. After an hour had passed with no other individuals seen, I called it a night and drove back to my camp at Bottomless Lakes, where the pre-dawn sky was a star-studded as I’ve ever seen!

Day 5

7 mi E of Queen, X Bar Rd

Eddy County, New Mexico

My original plan was to leave today and spend the next two days at Dog Canyon Campground in Guadalupe Mountains National Park just across the Texas state line. That would serve as a base from where I could service the traps that I have on the New Mexico side of the line and also afford me an opportunity to take a day off of collecting and hike the park’s spectacular system of trails. Unfortunately, when I went online a few days earlier to reserve my campsite, I learned that the campground was closed until December due to a water line break! This was a major disruption to my plans, because the only other campgrounds between Bottomless Lakes and Dog Canyon are private KOA-types (ugh!) and the dreadfully ugly Brantley Lake State Park! I decided then to keep my campsite at Bottomless Lakes and just drive to the Guadalupes to service my traps. Afterwards I would drive back and spend an extra night in the far roomier and more beautiful campground at Bottomless Lakes. Again, I was pleased to see the SRW trap hanging and intact, although the reservoir had developed a slow leak and was nearly drained. The catch, however, was still moist, suggesting that the leak had developed only recently and, thus, had no negative impact on data collection. The catch was similar to “San Jon Hill” in that there were numerous Enaphalodes hispicornis and smaller numbers of E. atomarius, Eburia haldemani, and a variety of smaller elaphidiines. Sadly, the SRW/EtOH trap had self-destructed—the bottom half of the trap was found lying on the ground not far from its still-hanging upper half (w/ bait even in the still-hanging bait bottle). The EtOH trap was also hanging and intact, though the bait bottle was dry (I’m seeing this pattern repeatedly—SRW and SRW/EtOH bait bottles still have some bait after 10 weeks in the field, but EtOH bait bottles are dry); however, there were only a few small elaphidiines representing the cerambycids. The white bottle trap had a decent catch of Acmaeodera spp. and bees (for Mike). However, there wasn’t much else going on insect-wise (the chunky, remarkably rock-like nymph of Leprus sp.—either L. intermedius [Saussure’s bluewinged grasshopper] or L. wheelerii [Wheeler’s bluewinged grasshopper]—notwithstanding).

The lack of insect activity had me ready to leave as soon as I finished retrieving the traps. However, as I was emptying the last jug trap, I noticed that Dasylirion leiophyllum (smooth sotol) was growing in the area and decided I should check them for Thrincopyge buprestids—colorful species that breed in the newly senesced flowering stalks of the plants. I checked a few without success and suspected it was probably too late in the season to find the adults, then broke an old flowering stalk off of one of the plants and saw the characteristic adult emergence holes of the beetles in the lower part of the stalk. This at least confirmed their presence in the area. Then I saw a plant with a newly senescing flowering stalk. Cutting into the lower portion of the stalk revealed a fresh, frass-packed larval gallery, suggesting larvae are currently working inside the stalk, so I broke the stalk from the plant, carried it back to the car, and cut/bundled it up for transport back home and placement in a rearing box. With luck, the larvae will complete their development to adulthood and emerge next spring.

5.6 mi E of Queen

Eddy County, New Mexico

On my last visit to the area, I found Cicindelidia laetipennis (polished-winged tiger beetle, formerly C. politula petrophila) just over the Texas state line at high elevations in Guadalupe Mountains National Park. I was hoping to see (and properly photograph) it again this time, but the closure of Dog Canyon Campground nixed those plans. Fortunately, I found an iNat record for the species on the New Mexico side of the line (in fact, less than two miles from my previous trapping spot) and made plans to see if I not only could find it but photograph it with the “big camera.” As it turned out, the habitat was perfect—a wash of exposed limestone on a short 2-track above 5000’ elevation.

For the majority of the time I was there, however, I didn’t see any individuals. I did find the occasional Acmaeodera rubronotata on flowers of Eriogonum hieraciifolium (hawkweed buckwheat) and a lumbering Tenebrionidae that I take to be Philolithus aeger crawling on the clay portion of the 2-track.

On the way back, however, I saw the first individual, and not too long afterwards I saw the second. These would be the only individuals I would see—not nearly enough to get my camera gear and hike back in an effort to get proper field photos. Once again, my previous iPhone photos will have to do for now.

Back at the car I was about to pack up and move on to my next trap location when I noticed Grindelia nuda (curlycup gumweed) in bloom around the parking area. Since I’d collected a small handful of A. rubronotata on buckwheat flowers, I thought I might check out the gumweed flowers as well. Not only did I find several more individuals of that species, I also found one individual of A. opacula (formerly A. disjuncta).

Klondike Gap Rd, Hamm Vista

Lincoln National Forest

Eddy County, New Mexico

As with the season’s previous two visits to this spot, the area looked dry and flowerless. Such conditions rarely warrant making the effort to take a closer look at things, and I wanted to get back to Bottomless Lakes with enough daylight left to search for tiger beetles at an area in the park that I not checked before—Lea Lake Recreation Area. With this in mind, I set about retrieving the traps and was happy to see the SRW trap hanging and intact (this trap was down last time due to rope failure). Also, even after nearly three months, the reservoir was moist and the bait bottle still had bait. There were lots of cerambycids in the catch, including several Enaphalodes hispicornis, E. atomarius, Tragidion coquus, Eburia haldemani, and smaller elaphidiines. The SRW/EtOH trap also, thankfully, was still hanging and in much the same condition as the SRW trap, but I did note far fewer cerambycids. This also seems to be the trend that I have noticed over the last two seasons of comparing these baits (although I must await stats analysis to see how real this is). The EtOH trap was also hanging and intact with plenty of liquid in the reservoir, but the bait bottle was dry (same as other locations), and there were hardly any cerambycids (same as some, but not all, other locations). Sadly, the white bottle trap was completely missing—I even managed to find the exact hole where it was pulled from, but the trap itself was nowhere in sight. This was frustrating, because it was by far the best-performing bottle trap on my last visit. I hate to think that someone deliberately stole it, but the thought is hard to resist—animals (primarily raccoons) often pull traps to eat the catch, but they don’t take the trap with them.

Lea Lake Recreation Area

Bottomless Lakes State Park

Chaves County, New Mexico

I’d been wanting to look for tiger beetles around Lea Lake since I arrived and was planning on today being the day. Unfortunately, the extra time I spent at the previous spots beyond retrieving the traps (i.e., for cutting up the sotol stalk and looking for Cicindelidia laetipennis)—along with an unplanned but needed stop for supplies—resulted in me arriving only 20 minutes before sundown. There was a particular tiger beetle species I was looking for—Cicindelidia haemorrhagica woodgatei (Woodgate’s tiger beetle), of which several observations from here had been posted on iNat. The alkaline flats right alongside the lake looked perfect for tiger beetles, and I immediately began finding and collecting a variety of tiger beetle species.

Most were expected—Eunota circumpicta johnsonii (Johnson’s tiger beetle), E. togata globicollis (alkali tiger beetle), and Cicindelidia ocellata ocellata (ocellated tiger beetle). One individual, however, gave me pause—both when I first saw it and then when I pulled it from the net. At first glance it looked like the über-common and widespread Cicindelidia punctulata (punctured tiger beetle), but it didn’t seem quite right for the species, and its dark coloration contrasted with the greenish color exhibited by most individuals in this area (representing the western subspecies, C. p. chihuahuas, or Chihuahua tiger beetle). Then I noticed the rather rounded elytral sides and the generally dull elytral surface and immediately suspected that I had just collected my first Cicindelidia nigrocoerulea (black sky tiger beetle)—a goal for the trip and one that I had not succeeded in finding at three locations I had gleaned from iNaturalist and visited earlier! Closer examination of the photo and the specimen convinced me I was correct, so even though I did not find the species I was looking for, I still found another one that was a priority for the trip. [Edit: after some discussion, the consensus on iNaturalist is that this individual represents C. punctulata. Alex Harmon noted the elytra sides aren’t round enough for C. nigrocoerulea and that the texture is better for C. punctulata. He also noted that, for what it is worth, that C. nigrocoerulea are either blue, green, or black rather than brown as in this individual. After looking at my field guide upon my return back home, I am inclined to agree with him.]

With the sun setting rapidly and so many tiger beetles still around, I decided that I would delay my departure from the area in the morning and come back to Lea Lake—perhaps I will still find C. h. woodgatei after all!

Pasture Lake Campground

Bottomless Lakes State Park

Chaves County, New Mexico

Back at camp after cooking dinner (salmon—more on this), I decided to “night walk.” I hadn’t had a chance to do this the previous two nights because of reasons, and I wanted to take advantage of one last opportunity to look for Amblycheila picolominii (plateau giant tiger beetle), which I found on both of my previous visits here this year. The closest and easiest place to get to where I had found one was at the bottom of the steep, narrow ravine coming off the gypsum/red siltstone slopes just behind my campsite, so I headed there first. Within minutes after clambering down into the bottom of the ravine, I found one!

Filled with optimism about finding more, I searched the remainder of the ravine bottom, but no more were seen. After emerging from the ravine back at the campsite, I sat at the table briefly to update my field notes before continuing to other areas. At one point I looked up, and there was another one right at my feet! I looked away briefly to grab a vial, and when I looked back it was gone—nowhere to be seen! I searched the entire campsite in a gradually enlarging spiral, but to no avail. I started questioning whether I had actually seen what I was sure I had seen—there are few places to hide anywhere in this very large campsite, and I could not understand how such a large and conspicuous beetle could completely evade me like that. That would ultimately prove to be the last individual “seen” during the entire evening. Nevertheless, during my spiral search I encountered an interesting situation at the “salmon oil pit” (I had rinsed the accumulated oils from the salmon before cooking it and dumped the wash into a small pit that I dug in the soil). There were two tiger beetles inside the pit—Tetracha carolina carolina (Carolina metallic tiger beetle) and Eunota circumpicta johnsonii (Johnson’s tiger beetle)—presumably scavenging on the tasty oils saturating the soil (tiger beetles are well known scavengers when the opportunity arises).

Also during my spiral search, I found several Cysteodemus wislizini (black bladder-bodied blister beetle), each perched on the foliage of Tribulus terrestris (puncture vine). I didn’t know if there was any significance to the association, but I found them on no other plant (the significance would be revealed the next morning). Lastly, I encountered several individuals of a tank-like species of Stenomorpha darkling beetle in the mesquite/saltbush chaparral next to the campsite. I am unsure of the species (the genus is super diverse), but I collected a few specimens and will eventually update their identity in the iNat observation that I posted.

I spent a fair bit of time walking the roads afterwards and even went to the picnic area on the other side of Pasture Lake Campground to see if I could find more A. picolominii, but as alluded to earlier that effort would prove futile. At the end of the fifth collecting episode for the day (interspersed with five hours of driving), I collapsed exhausted onto my cot with a few minutes to spare before midnight!

Day 6

As I was drinking my morning coffee and working on yesterday’s field notes, I noticed another Cysteodemus wislizini (black bladder-bodied blister beetle) on Tribulus terrestris (puncture vine) where I had collected a few on the same plants the night before. This one, however, was not only perched on the plant, but also consuming its flowers. I would see two more on the same plants during the course of the morning, so it seems there is at least an adult floral host association between the beetle and this plant.

Lea Lake Recreation Area

Bottomless Lakes State Park

Chaves County, New Mexico

Before leaving the park, I wanted to spend some time looking for tiger beetles at Lea Lake. I’d gotten only a quick taste of the fauna there with yesterday’s 20-minutes-before-sunset visit, during which time I’d collected four species, including the new-for-me Cicindelidia nigrocoerulea (black sky tiger beetle), and I was hoping today to add a fifth—Cicindelidia haemorrhagica woodgatei (Woodgate’s tiger beetle) which has been reported here several times already. This time I started at the east end of the alkaline flats, seeing and collecting another C. nigrocoerulea as well as a few individuals each of the other three species I’d seen yesterday—Cicindelidia ocellata ocellata (ocellated tiger beetle), Eunota circumpicta johnsonii (Johnson’s tiger beetle), and Eunota togata globicollis (alkali tiger beetle)—on the alkaline flats along the lake margin. I noticed Isocoma pluriflora (southern goldenbush) at the far end of the flats and checked them for Crossidius suturalis, finding a handful of individuals on the flowers, before turning my attention back to tiger beetles and working my way towards the west side of the lake. I wanted to get proper field photographs of the species I had not yet done so (at least, with the “big camera”), which at that point were only C. nigrocoerulea and C. o. ocellata. I never did see another of the former, but the latter were common enough that I was able to “work” a few individuals before finding a (relatively) cooperative one. I hadn’t planned on collecting any more individuals of E. c. johnsonii, but then I encountered two beautifully sumptuous green individuals and couldn’t resist.

Shortly afterwards, I noticed several individuals of a species I’d not yet seen at that location—Cicindelidia tenuisignata (thin-lined tiger beetle)—in an area of the alkaline flats that was wet from lake water lapping over the edge. I was able to not only collect a handful of specimens, but also get decent photographs of one of them—making moot my inability yesterday to photograph this species and C. o. ocellata.

In the same area, I thought I’d collected a third C. nigrocoerulea, but it turned out to be the common Cicindelidia punctulata (punctured tiger beetle) with which it can be confused. Interestingly, it was dark-colored (as in the eastern subspecies—C. p. punctulata), not green (as in the western subspecies—C. p. chihuahuae). In the end, the number of species seen around the lake increased to six, but—unfortunately for me—C. h. woodgatei was not one of them. By then I’d been at it for two hours, and the heat of the day (99°F) was upon me. Such temps are no good for trying to photograph tiger beetles, so I found some shelter to eat a bit of lunch and then started west towards my next set of traps at a high elevation site near Cloudcroft.

Switchback Trailhead

Lincoln National Forest

Otero County, New Mexico

I always enjoy the drive from Roswell to Cloudcroft—searing desert heat yields to cool mountain air, and the landscape morphs from a flat, featureless, heavily-populated (and, thus, littered) plain, to sweeping, undulating hills of juniper chaparral, to foothills of oak woodland, and finally to bonafide mountains with dense forests of stately pines and firs.

Poetically, I was greeted at the higher elevations by not only cool air, but rain (I think it has done this on every trip I’ve made in this direction). The rain was nothing more than sprinkles, though with a brief 1–2-minute windshield-cleaning episode. By the time I reached my trap locality, clouds remained, but the rain had moved on. I picked this locality because of its ease of access to the precise habitat I wanted to sample—Gamble’s oak forest. When I first encountered the location in May (and again when I returned to service the traps in June), the area was deserted—just what I want in a trapping locality to minimize the chance of vandals finding and disturbing the traps. This time, however, I was horrified to find the area choked with vehicles and tents—the place was literally teeming with people. I got a bad feeling in the pit of my stomach about whether I would find my traps still hanging and intact, and these fears were confirmed when I approached the location of the SRW trap and found it was completely missing—not a shred of evidence that the trap had ever been there! This was really disappointing for obvious reasons, but, additionally, this was the trap that produced the most interesting catch of all traps at all locations on the previous visit. Fortunately, the SRW/EtOH trap was still hanging and intact with liquid in the reservoir and bait in the bottle. The catch was voluminous and appeared to consist largely of flies, yellowjackets, and butterflies; however, fingering through it I did find some interesting longhorned beetles: Tragidion coquus, Stictoleptura canadensis (a new addition to the list of species trapped), and the previously captured Stenocorus copei. This lifted my spirits a bit knowing that at least one trap had survived the human onslaught. The lift, however, was short lived when I approached the EtOH trap and found it lying on the ground—completely disassembled! I found most of the parts, but the nylon rope and carabiner used to hang the trap were gone—someone actually had to untie the rope at one end and unclip the carabiner at the other to take them. I really don’t understand the depravity of people that mess with other people’s stuff with no regard or remorse. Vandalizing traps not only wastes my time, effort, and expense, but in this case it also negatively impacts the integrity of the study I am conducting. It’s hard enough trying to anticipate and mitigate against weather, animals, equipment failure, and errors in deployment without also having to outfox the criminal element. I’ll have to consult with a statistician on the best way to analyze the trapping results while taking into account the loss of some trap events (i.e., unique trap/date combinations). On a positive note, the white bottle trap that I reset last time was still in place and had captured a nice quantity of both Acmaeodera and Anthaxia.

Hwy 70 at “Point of Sands”

Otero County, New Mexico

After checking the traps near Cloudcroft, my original plan was to camp at Upper Karr Canyon, a high elevation national forest campground south of Cloudcroft. However, seeing the zoo of campers at the trapping site, along with the throngs of people and cars I’d seen in town, suggested to me that any campground in the area was probably already filled to capacity on what I realized was a Saturday night of a holiday weekend (Monday is Mexican Independence Day). I noted that my next trapping location at Aguirre Springs Campground in the Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument was another 2-hour drive, but that I had plenty of time to make it there before dark—even if I stopped and collected along the way. Heading straight there wouldn’t solve the problem of finding an open campsite on a Saturday night, but at least the location was further removed from a town teeming with visitors. As for collecting along the way, I could think of no better spot than “Point of Sands”—a spot along U.S. Hwy 70 where the dunes of White Sands National Monument breach the fenceline and continuously spill out onto the highway. It’s a chance to get a quick taste of the dune flora and fauna without the need for permits, entry fees, etc. I stopped here also on both trips earlier this season, and while I didn’t find much out of the ordinary either time, I keep returning for two reasons—Acmaeodera recticollis and Sphaerobothris ulkei, two rather uncommon and desirable buprestid species that breed in Ephedra (jointfir). I collected a small series of the former here a couple of years ago, but my only evidence that the latter occurs here is a carcass I found lying on the ground a few years earlier. Someday, I will come to this spot at the right time and find adults of that species active on the Ephedra. Once again, however, that time would not be this time—despite the much more comfortable conditions than last time (when temps were 108°F), the only insect I saw worth putting into a bottle was the tank-like darkling beetle, Philolithus aeger, crawling on the white sand.

I also had hopes of finding Crossidius longhorned beetles when I noted stands of Isocoma pluriflora (southern goldenbush) and Gutierrezia sarothrae (broom snakeweed) in bloom—both of which are favored hosts for beetles in this genus. None were found, however—just blister beetles, so after completing the circuit up one side of the road and down the other, I continued the drive to Aguirre Springs.

Aguirre Springs Campground

Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument

Doña Ana County, New Mexico

My fears about the campground being filled seemed realized as I entered the loop and saw site after site already occupied. Fortunately, on the backside of the loop I found a few unoccupied sites, one of which was quite nice—buffered from the view of the road and nearby sites by trees and shrubbery and with a nice level area for the tent. It felt good to be back in one of my favorite places, and another “dirty burger” dinner tasted quite good!

Afterward, I walked the loop to see if I could find any beetles (hoping for Amblycheila, of course), but the only thing I saw were the occasional Eleodes darkling beetle and the glowing eyes of spiders, including the always charismatic Geolycosa sp. (burrowing wolf spider).

Day 7

In the morning, I decided to relax a bit and work on my field notes while enjoying coffee and the views, then headed out to retrieve my traps.

Yesterday’s poor trap fortune turned around completely when all three traps were found in place, intact, … and loaded with beetles! These included several species of elaphidiine longhorned beetles and a diversity of cetoniine scarabs. Two species of the latter group were Cotinis mutabilis (figeater beetle) and Gymnetina cretacea sunbbergi—both new for me! I don’t think the former is all that uncommon, but the latter apparently represents a recently-described subspecies that is endemic to the Organ Mountains.

The same pattern of fewer beetles in the EtOH trap was found here, although all three traps displayed greater total mass than their respective counterparts at other locations. After retrieved the EtOH trap, it hit me that I had just taken down the last trap at the last location in the final season of the 3-year study! There is still much work still to do—specimens to sort, prep, mount, and identify… data to assemble, crunch, and ponder… manuscripts to write, polish, submit, and revise… co-authors to correspond with and coordinate. However, with all that said, finishing the field work still feels like a major victory! At this point, I have no other place where I must go, so I am content to spend the rest of the trip exploring this beautiful area (this makes up for me not getting to spend a day hiking in Guadalupe Mountains National Park).

As I was retrieving the traps, I scanned the nice variety of plants in bloom for beetles and quickly encountered not only Crossidius pulchellus on flowers of Gutierrezia sarothrae (broom snakeweed), but also Acmaeodera opacula, A. amplicollis, and A. rubronotata on the same as well. These are all late-season, mid- to high-altitude species, and surely the floral associations are well known. However, i did find two potential new ones—A. amplicollis (observed) and A. rubronotata (collected) on flowers of Pectis papposa (chinchweed). I don’t recall encountering this plant in my review of literature on host associations of North American Buprestidae and will have to look into this when I return from the field.

On the way back to camp to drop off the traps and refuel, I saw a Euphoria verticalis crawling on the broken granite substrate.

I’d gotten iPhone images of three of the Gutierrezia-associates, but since I have some flex time I decided to grab the big camera and see what kind of real photos I could get. I walked to an area with blooming Gutierrezia much closer to my camp on the south side. I found several C. pulchellus, photographing a mating pair, but persistent searching beyond the area never turned up any of the buprestids. So I looped back through the campground and walked back to the ravine I’d visited earlier. There, back up and down the ravine, I photographed C. pulchellus, A. rubronotata, and A. amplicollis (I never saw another A. opacula beyond the first). I then tuned my attention to other subjects: a snout butterfly, a scoliid wasp, a few plants, and something for a future quiz. I was content with the day and strolled back to camp to rest and cook dinner (steak!).

After dinner (and a thrilling football game between my beloved Chiefs and rival Bengals!), I did my “night walk,” this time leaving the campground loop and walking along Aguirre Springs Rd a short distance before turning back. Again, I encountered Eleodes darkling beetles—this time congregating on the trunk of a very large juniper cadaver—and the siren call of a wolf spider’s glowing eyes luring me in for images. I managed a dorsal shot, but she skedaddled before I could fire off a frontal portrait. [Edit: discussion on iNaturalist suggests this is an undescribed species currently known as the “big-eyed” Hogna with its pale, ghost-like markings. It seems to be common in New Mexico.]

The waxing gibbous moon threw enough light on the majestic peaks above to make for one the most beautiful night skies you’ll ever see!

Day 8

I didn’t sleep well—my stomach began rumbling in the middle of the night, and by the time I got up I had full-blown GI problems. I had wanted to go down to lower elevations before the temperatures got too high in hopes of finding late-season “hangers on” of larger southwestern buprestids in the genera Gyascutus and Lampetis, but it seemed prudent instead to take it easy during the morning and give myself a chance to feel better. This did seem to happen… eventually… or perhaps it was just the product of wishful thinking!

Bar Canyon Trail

Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument

Doña Ana County, New Mexico

I went to a spot where late-season occurrences of Gyascutus, Lampetis, and Acmaeodera had been recorded on iNat.

I got an early indication of good luck when I found Acmaeodera rubronotata and A. opacula on the flowers of Picradeniopsis absinthifolia (hairyseed bahia). I also found another Cotinis mutabilis (figeater beetle), this one on flowers of Gutierrezia sarothrae right around the parking lot.

A bit further up the trail, I found two additional species—A. amplicollis and A. maculifera—also on P. absinthifolia, and further still along the trail I found more of the former.

Alongside the trail was a wash, where Fallugia paradoxa (Apache plum) was growing—checking the flowers was, for the most part, fruitless; however, I did find on them singletons of A. opacula and A. rubronotata. There were other plants in flower as well that seemed like they should be good beetle hosts—notably Gymnosperma glutinosum (gumhead), from which I collected a single A. rubronotata. Otherwise, however, there was little to be seen (except the occasional monstrous lubber grasshopper).

I was happy to see the variety of Acmaeodera on P. absinthifolia flowers—especially A. maculifera, a species I had not seen for two decades(!), but my GI problems seemed to worsen as I felt increasingly weak and overheated. Less than one mile up the trail, I simply couldn’t continue further and turned back towards the car for—what I thought—was an end to the day’s activities.

North Fork Las Cruces Arroyo

Doña Ana County, New Mexico

After a quick stop in town to purchase symptom relief, I intended to go straight back to the campground and rest for the remainder of the day. Apparently unable to stick to a good plan, however, I decided to scan iNat one last time to see if there were interesting records of Buprestidae from nearby areas and saw that A. maculifera had been taken in a wash just a few miles away. I couldn’t resist the temptation to take one more look at one more spot before heading back up the mountain. Walking down into the wash felt like descending into a furnace! It was by then mid-afternoon, and even though I had rehydrated I still felt weak on the feet. The promise of beetles, however, continued singing its siren song, and I quickly found what proved to be Heterotheca zionensis (Zion false goldenaster) abundantly in bloom and looking like a perfect host for Acmaeodera.

At first I found nothing, but with continued searching I found a spot where several Crossidius pulchellus and a single Acmaeodera scalaris were seen clinging to its flowers—the latter being another buprestid species for the trip (though, admittedly, a rather common species). I managed to finally find several A. maculifera on the flowers after additional searching (along with A. opacula), but I was declining rapidly and decided best to turn around. Passing near the spot where I had first found beetles, I found more A. maculifera (along with A. rubronotata) and lingered to better my series. This last little delay, however, proved to be too much for me, and for the first time ever I experienced “being sick” in the field! My body was sending me a message, and it was loud and clear (not that it wasn’t loud and clear before then!). I went back up the mountain and spent the rest of the day sleeping and resting in the cool mountain air back at camp.

Day 9

My original plan for the day (depending on how I was feeling) was to break camp and start heading back to the northeast. With luck, I would make it to the Oklahoma panhandle with enough daylight to explore a few localities in Texas Co. that I hadn’t visited before. I did get a much better night’s sleep; however, I still felt weak and had to take my time breaking camp. This delayed my planned early morning departure a bit, and the need for frequent stops made a pre-evening arrival even less likely. In the end, it didn’t matter as rain moved through the area, bringing abruptly cool, cloudy conditions and wiping out any hope of any insect activity in the waning hours of the day. I did, however, get to see an oversized Texan as I sliced through the uppermost tip of that oversized state and was greeted by an ironically hypocritical welcome sign as I entered adjacent Oklahoma.

Day 10

3.2 mi SSW of Piqua

Woodson County, Kansas

I got another text yesterday from Dan Heffern, who told me that his brother had found several Megacyllene decora (amorpha borer) on Amorpha fruticosa near his home in eastern Kansas. I had already checked the nearby locality near Piqua (where he had seen this species many years ago) without success, but I reasoned that it may have been too early and that another look (now that the species is known to be out) was warranted. I was feeling better, but not great, and was, thus, glad to encounter relatively mild conditions when I arrived. On the very first clump of Amorpha that I checked, I found a big Megatibicen dorsatus (bush cicada) female sitting on its stem, …

…and shortly afterwards I found the left elytron of M. decora on the ground amidst Amorpha and flowering Solidago sp.

“What luck!”, I thought, and proceeded to inspect each Amorpha clump and flowering Solidago that I could find. Remarkably, my search for adults would prove fruitless, and for the second time on the trip I would have to walk away from the spot empty-handed. I was also starting to feel weak and overheated again after an hour of searching, suggesting that I was still not recovered and that perhaps I should focus on finishing the drive to St. Louis so I could recover in the comfort of my home—a rather inauspicious ending to what was, by all other measures, as fun and successful a collecting trip as I could ever hope for!

©️ Ted C. MacRae 2024