![]() When Chris Brown and I began our study of Missouri tiger beetles back in 2000, our goal was simply to conduct a faunal survey of the species present in the state. Such studies are fairly straightforward—examine specimens in the major public and private collections, and do lots and lots of collecting, especially in areas with good potential for significant new records. Over the next 10 years, however, our study morphed from a straightforward faunal survey to a series of surveys targeting a number of species that seemed in need of special conservation attention. We were no longer just collecting tiger beetles, but trying to figure out how to save them.

When Chris Brown and I began our study of Missouri tiger beetles back in 2000, our goal was simply to conduct a faunal survey of the species present in the state. Such studies are fairly straightforward—examine specimens in the major public and private collections, and do lots and lots of collecting, especially in areas with good potential for significant new records. Over the next 10 years, however, our study morphed from a straightforward faunal survey to a series of surveys targeting a number of species that seemed in need of special conservation attention. We were no longer just collecting tiger beetles, but trying to figure out how to save them.

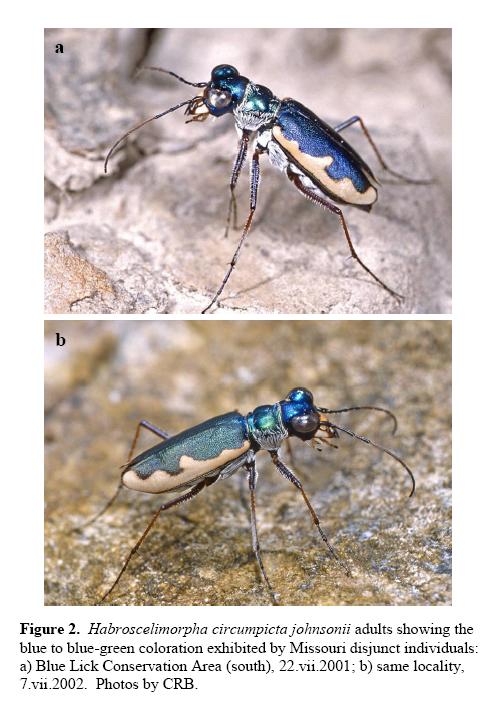

There were good reasons for this—Missouri’s tiger beetle fauna is rather unique due to the state’s ecotonal position in the North American continent. While its faunal affinities are decidedly eastern, there are also several Great Plains species that range into the state’s western reaches. Even more interestingly, these western species occur in Missouri primarily as relict populations—widely disjunct from their main geographic ranges further west, and limited in Missouri to small geographical areas where just the right conditions still exist. These include the impressive (and thankfully secure) Cicindela obsoleta vulturina (prairie tiger beetle), the likely extirpated Habroscelimorpha circumpicta johnsonii (Johnson’s tiger beetle, with Missouri’s disjunct population often referred to as the ‘saline spring tiger beetle’), Cylindera celeripes (swift tiger beetle)—still clinging precariously to existence throughout much of its former range, and the subject of our newest publication, Dromochorus pruinina (frosted dromo tiger beetle) (MacRae and Brown 2011).

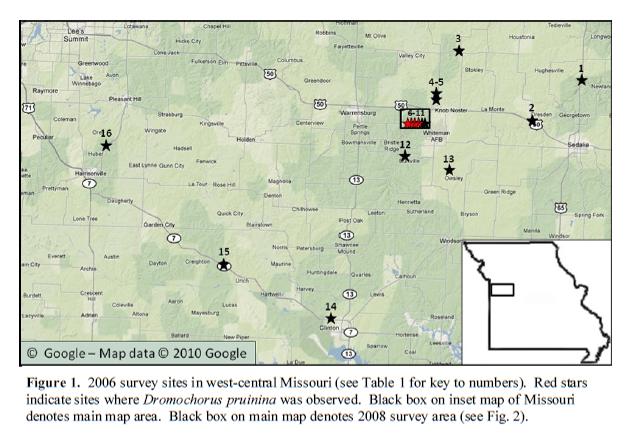

We were first made aware of the occurrence of this species in Missouri when Ron Huber (Bloomington, MN) sent us label data from 7 specimens in his collection. One was labeled from Columbia, Missouri—location of the University of Missouri, and source of many a mislabeled specimen culled from collections of entomology students. The other specimens, however, collected in 1975 and labeled “10 miles W of Warrensburg” in western Missouri, seemed legit, and in 2003 we began searching in earnest for this species. Our searches in the vicinity of 10 miles W of Warrensburg were not successful (and, in fact, we had difficulty even locating habitat that looked suitable), but on 15 July 2005 Chris found the species on eroded clay roadsides along County Road DD in Knob Noster State Park—precisely 10 mi east of Warrensburg. With this collection as a starting point, we began an intense pitfall trapping effort in 2006 to more precisely define the geographical extent of this population in Missouri. The Knob Noster population was confirmed at several spots along the 2.5-mile stretch of Hwy DD that runs through Knob Noster State Park, but we were surprised to find no evidence of this species at any other location throughout a fairly broad chunk of west-central Missouri (see Fig. 1 above). We examined the area thoroughly in our search to find suitable habitats for placing pitfall traps, and it became quite obvious that the eroding clay banks that harbored the species in Knob Noster State Park were not extensive in the area. This observation also seemed to further confirm our suspicion that the label data for the original 1975 collection were slightly erroneous, and that the Knob Noster population was, in fact, represented by that original 1975 collection.

We were first made aware of the occurrence of this species in Missouri when Ron Huber (Bloomington, MN) sent us label data from 7 specimens in his collection. One was labeled from Columbia, Missouri—location of the University of Missouri, and source of many a mislabeled specimen culled from collections of entomology students. The other specimens, however, collected in 1975 and labeled “10 miles W of Warrensburg” in western Missouri, seemed legit, and in 2003 we began searching in earnest for this species. Our searches in the vicinity of 10 miles W of Warrensburg were not successful (and, in fact, we had difficulty even locating habitat that looked suitable), but on 15 July 2005 Chris found the species on eroded clay roadsides along County Road DD in Knob Noster State Park—precisely 10 mi east of Warrensburg. With this collection as a starting point, we began an intense pitfall trapping effort in 2006 to more precisely define the geographical extent of this population in Missouri. The Knob Noster population was confirmed at several spots along the 2.5-mile stretch of Hwy DD that runs through Knob Noster State Park, but we were surprised to find no evidence of this species at any other location throughout a fairly broad chunk of west-central Missouri (see Fig. 1 above). We examined the area thoroughly in our search to find suitable habitats for placing pitfall traps, and it became quite obvious that the eroding clay banks that harbored the species in Knob Noster State Park were not extensive in the area. This observation also seemed to further confirm our suspicion that the label data for the original 1975 collection were slightly erroneous, and that the Knob Noster population was, in fact, represented by that original 1975 collection.

In 2008, we conducted additional pitfall trapping surveys tightly concentrated in and around Knob Noster State Park. Again, we only found the beetle along the same 2.5-mile stretch of Hwy DD, despite the presence of apparently suitable eroded clay roadsides in other parts of the park. These other areas were either disjunct from the Hwy DD sites, separated by woodlands that this flightless species likely is not able to traverse, or were fairly recently formed through road construction activities. These newly formed bare clay roadsides were quite close to the beetle sites, and we are still hard pressed to explain why the beetle has apparently not yet colonized them—perhaps there is some physical or chemical property that the beetle requires that is not present in these more anthropogenically formed habitats. Whatever the explanation, the result is the same—the entire Missouri population of D. pruinina appears to be restricted to a scant 2.5-mile stretch of roadside habitat in west-central Missouri, disjunct from the nearest population further west (Olathe, Kansas) by a distance of 75 miles. The highly restricted geographical occurrence of this species in Missouri is cause enough for concern about its long-term prospects, but the relatively low numbers of adults that were encountered—38 throughout the course of the study—is even more troubling. Dromochorus pruinina is not extirpated in Missouri, but the prospect of such is a little too real for comfort.

In 2008, we conducted additional pitfall trapping surveys tightly concentrated in and around Knob Noster State Park. Again, we only found the beetle along the same 2.5-mile stretch of Hwy DD, despite the presence of apparently suitable eroded clay roadsides in other parts of the park. These other areas were either disjunct from the Hwy DD sites, separated by woodlands that this flightless species likely is not able to traverse, or were fairly recently formed through road construction activities. These newly formed bare clay roadsides were quite close to the beetle sites, and we are still hard pressed to explain why the beetle has apparently not yet colonized them—perhaps there is some physical or chemical property that the beetle requires that is not present in these more anthropogenically formed habitats. Whatever the explanation, the result is the same—the entire Missouri population of D. pruinina appears to be restricted to a scant 2.5-mile stretch of roadside habitat in west-central Missouri, disjunct from the nearest population further west (Olathe, Kansas) by a distance of 75 miles. The highly restricted geographical occurrence of this species in Missouri is cause enough for concern about its long-term prospects, but the relatively low numbers of adults that were encountered—38 throughout the course of the study—is even more troubling. Dromochorus pruinina is not extirpated in Missouri, but the prospect of such is a little too real for comfort.

As a result of our studies, D. pruinina is now listed as a state species of conservation concern with a ranking of “S1” (critically imperiled)—the highest possible ranking (Missouri Natural Heritage Program 2011). Despite its highly restricted range in Missouri, the occurrence of this population entirely within the confines of Knob Noster State Park under the stewardship of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) provides some measure of optimism that adequate conservation measures will be devised and implemented to ensure the permanence of this population. Chief among these is the maintenance of existing roadside habitats, which are kept free of woody vegetation by a combination of mowing and xeric conditions. True conservation of the beetle, however, can only occur if the area of suitable habitat is significantly expanded beyond its present extent. Much of the park and surrounding areas are heavily forested and, thus, do not provide suitable habitat for the beetle. Significant areas within the park have been converted in recent years to open woodlands and grasslands; however, these areas still possess a dense ground layer and lack the patchwork of barren slopes that seem to be preferred by the beetle. Further conversion of these areas to grasslands with more open structure will be required to create additional habitats attractive to the beetle. Until this is done, D. pruinina is at risk of meeting the same fate that has apparently befallen the Missouri disjunct population of H. circumpicta johnsonii (Brown and MacRae 2011).

REFERENCES:

Brown, C. R. and T. C. MacRae. 2011. Assessment of the conservation status of Habroscelimorpha circumpicta johnsonii (Fitch) in Missouri. CICINDELA 42(4) (2010):77–90.

MacRae, T. C. and C. R. Brown. 2011. Distribution, seasonal occurrence and conservation status of Dromochorus pruinina (Casey) in Missouri CICINDELA 43(1):1–13.

Missouri Natural Heritage Program. 2011. Species and Communities of Conservation Concern Checklist. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, 52 pp.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2011