The December 2010 issue of the journal CICINDELA came out a little over a week ago. Leading off inside is the first in a series of papers that I, along with colleagues Chris Brown and Kent Fothergill, have prepared detailing our work with several species of tiger beetles in Missouri of potential conservation interest. At the start of our surveys, Missouri’s tiger beetle fauna was already fairly well characterized, at least qualitatively, due to the efforts of heavy hitters Ron Huber and Dave Brzoska, who for many years lived in nearby eastern Kansas. Despite their attentions, however, questions lingered regarding the precise distribution and status of several species of restricted geographical occurrence within the state, and our surveys over the past 10 years have sought to resolve these questions and, if necessary, recommend conservation efforts to secure the long-term survival of these species within the state.

The December 2010 issue of the journal CICINDELA came out a little over a week ago. Leading off inside is the first in a series of papers that I, along with colleagues Chris Brown and Kent Fothergill, have prepared detailing our work with several species of tiger beetles in Missouri of potential conservation interest. At the start of our surveys, Missouri’s tiger beetle fauna was already fairly well characterized, at least qualitatively, due to the efforts of heavy hitters Ron Huber and Dave Brzoska, who for many years lived in nearby eastern Kansas. Despite their attentions, however, questions lingered regarding the precise distribution and status of several species of restricted geographical occurrence within the state, and our surveys over the past 10 years have sought to resolve these questions and, if necessary, recommend conservation efforts to secure the long-term survival of these species within the state.

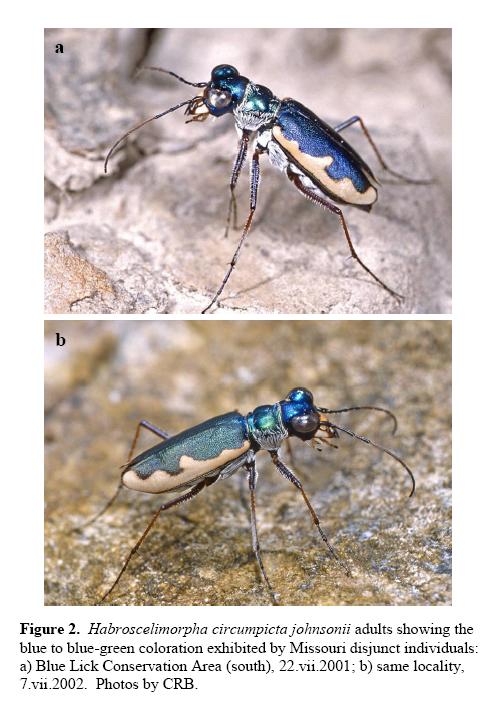

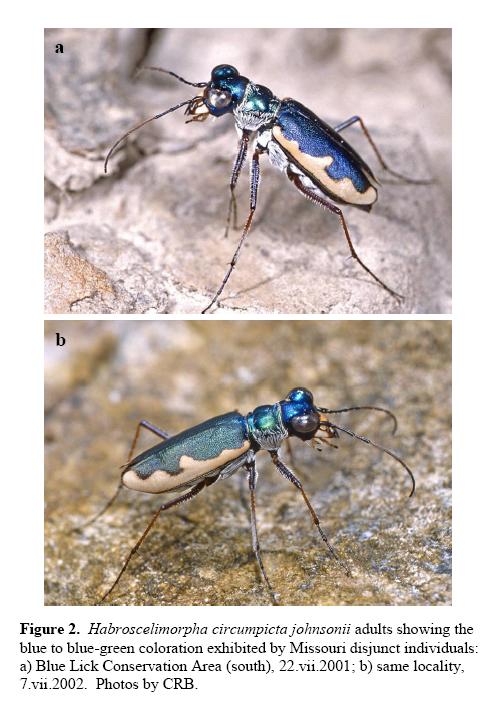

One of these species of interest is Habroscelimorpha circumpicta johnsonii (Johnson’s tiger beetle). This subspecies is widely distributed in inland areas of the central and south-central United States, where it is associated exclusively with barren areas surrounding saline seeps. Despite the broad occurrence of the main population, the Missouri population of this subspecies has long been of particular interest for several reasons: 1) its widely disjunct isolation, occurring several hundred miles east of the nearest populations in central Kansas, 2) its strict association with the highly restricted saline seeps of central Missouri (Fig. 1), and 3) the exclusive blue-green coloration of the adults (Fig. 2) that contrasts with the varying proportions of reddish and/or dark morphs, in addition to blue-green morphs, found in other populations. The highly disjunct and isolated occurrence of this population and its unique coloration have been considered by some workers as grounds for separate subspecific status. Another restricted, disjunct population of this species in North Dakota has already been accorded subspecific status – H. circumpicta pembina.

One of these species of interest is Habroscelimorpha circumpicta johnsonii (Johnson’s tiger beetle). This subspecies is widely distributed in inland areas of the central and south-central United States, where it is associated exclusively with barren areas surrounding saline seeps. Despite the broad occurrence of the main population, the Missouri population of this subspecies has long been of particular interest for several reasons: 1) its widely disjunct isolation, occurring several hundred miles east of the nearest populations in central Kansas, 2) its strict association with the highly restricted saline seeps of central Missouri (Fig. 1), and 3) the exclusive blue-green coloration of the adults (Fig. 2) that contrasts with the varying proportions of reddish and/or dark morphs, in addition to blue-green morphs, found in other populations. The highly disjunct and isolated occurrence of this population and its unique coloration have been considered by some workers as grounds for separate subspecific status. Another restricted, disjunct population of this species in North Dakota has already been accorded subspecific status – H. circumpicta pembina.

Despite its restricted occurrence in Missouri, a long history of collection records exist for the subspecies. Numerous specimens are housed in the Enns Entomology Museum in Columbia, Missouri, with a majority of these coming from a single location (Boone’s Lick Historic Site) and dating back as early as 1954. In more recent years (1985-1992), Ron Huber and Dave Brzoska found significant numbers of beetles at two additional locations near Boone’s Lick. Despite these numerous records, the subspecies was listed as a “Species of Conservation Concern” by the Missouri Natural Heritage Program with a status of “S2S3” (vulnerable or imperiled) due to the rarity of its required saline seep habitats in Missouri. Unfortunately, this alone did not appear to be sufficient protection for the species, as my own observations beginning in the mid-1990s suggested that populations of the beetle had declined significantly from their historical levels. Concomitant with these apparent declines was the observation that the sites supporting these beetles had themselves suffered severe degradation that reduced their apparent suitability as habitat for the beetle. As a result of these observations, Chris and I initiated comprehensive surveys during the 2001 field season to assess the conservation status of the Missouri population and identify potential new sites. Our first order of business was to petition a status change to “S1” (critically imperiled), and for the next three years we regularly visited the historical sites throughout the presumed adult activity period, noting occurrence of adults and recording their numbers and the circumstances of their habitat associations. Included in these surveys also were two new sites identified using the Missouri Natural Heritage Database.

Despite its restricted occurrence in Missouri, a long history of collection records exist for the subspecies. Numerous specimens are housed in the Enns Entomology Museum in Columbia, Missouri, with a majority of these coming from a single location (Boone’s Lick Historic Site) and dating back as early as 1954. In more recent years (1985-1992), Ron Huber and Dave Brzoska found significant numbers of beetles at two additional locations near Boone’s Lick. Despite these numerous records, the subspecies was listed as a “Species of Conservation Concern” by the Missouri Natural Heritage Program with a status of “S2S3” (vulnerable or imperiled) due to the rarity of its required saline seep habitats in Missouri. Unfortunately, this alone did not appear to be sufficient protection for the species, as my own observations beginning in the mid-1990s suggested that populations of the beetle had declined significantly from their historical levels. Concomitant with these apparent declines was the observation that the sites supporting these beetles had themselves suffered severe degradation that reduced their apparent suitability as habitat for the beetle. As a result of these observations, Chris and I initiated comprehensive surveys during the 2001 field season to assess the conservation status of the Missouri population and identify potential new sites. Our first order of business was to petition a status change to “S1” (critically imperiled), and for the next three years we regularly visited the historical sites throughout the presumed adult activity period, noting occurrence of adults and recording their numbers and the circumstances of their habitat associations. Included in these surveys also were two new sites identified using the Missouri Natural Heritage Database.

The results were not good – during the 3-year survey, only a single beetle was observed at the historical location of Boone’s Lick, and none were observed at the two other locations discovered by Ron Huber and Dave Brzoska. More significantly, all three sites had suffered severe degradation due to vegetational encroachment, cattle trampling, or other anthropogenic disturbance. Moreover, of the two potential new sites identified, only one of these (Blue Lick Conservation Area) was found to support a small population of the beetle. Three apparently suitable saline seeps exist at this latter site; however, beetles were observed at only one of them. During the final year of the survey, prolonged flooding occurred at this site (frustratingly, a result of earth-moving operations by site personnel), which was followed in subsequent years by significant vegetational encroachment (Fig. 3). No beetles were observed at this site during the final year of the survey, nor has the species been seen there in multiple visits to the site in the years since.

The results were not good – during the 3-year survey, only a single beetle was observed at the historical location of Boone’s Lick, and none were observed at the two other locations discovered by Ron Huber and Dave Brzoska. More significantly, all three sites had suffered severe degradation due to vegetational encroachment, cattle trampling, or other anthropogenic disturbance. Moreover, of the two potential new sites identified, only one of these (Blue Lick Conservation Area) was found to support a small population of the beetle. Three apparently suitable saline seeps exist at this latter site; however, beetles were observed at only one of them. During the final year of the survey, prolonged flooding occurred at this site (frustratingly, a result of earth-moving operations by site personnel), which was followed in subsequent years by significant vegetational encroachment (Fig. 3). No beetles were observed at this site during the final year of the survey, nor has the species been seen there in multiple visits to the site in the years since.

Is the Missouri disjunct population of Johnson’s tiger beetle extirpated? There is little reason to be optimistic. What is clear is that the beetle is now below detectable limits, and with the loss of suitable habitat at all sites known to have supported the beetle in the past and little chance that new, high-quality sites will be identified, prospects for an unaided comeback are dim. The saline seep habitats at the three historic sites appear to have suffered irreparable degradation and offer little restoration potential to the degree required to support viable beetle populations; however, there are still two saline seeps at Blue Lick that do offer at least a semblance of suitable habitat. It is imperative that these last remaining examples of Missouri’s critically imperiled saline seeps habitats receive the highest priority for protection if the beetle (should it still exist) is to have any chance of surviving in Missouri. Johnson’s tiger beetle is only one of several tiger beetle species whose presence in Missouri appears to be in jeopardy (others being Dromochorus pruinina – loamy ground tiger beetle, and Cylindera celeripes – swift tiger beetle). I end this post with our closing admonition in the paper:

The loss of this beautiful and distinctive beetle from Missouri’s native fauna would represent a significant and tragic loss to this state’s natural heritage. We urge the Missouri Department of Conservation, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, and other conservation organizations within the state to identify and allocate the resources needed to develop and implement a recovery plan for the species in Missouri.

REFERENCE:

Brown, C. R. and T. C. MacRae. 2011. Assessment of the conservation status of Habroscelimorpha circumpicta johnsonii (Fitch) in Missouri CICINDELA 42(4) (2010):77-90.

Postscript. On a happier note, I am pleased to be joining the editorial staff for CICINDELA. While my role as layout editor is more functional than academic, I am nevertheless thrilled with the chance to “rub shoulders” with the likes of Managing Editor Ron Huber and long-time cicindelid experts Robert Graves and Richard Freitag. I hope my contributions to the journal’s production on the computer end of things will be favorably received by its readership.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2011