I’d had a very enjoyable 2nd day on this year’s fall tiger beetle trip, but I couldn’t say it had been particularly successful. My primary reason for coming to the Glass Mountains in northwestern Oklahoma was to confirm a hunch that the stunningly beautiful Cicindela pulchra (Beautiful Tiger Beetle) might occur in the flats below the area’s red mesas. My hunch was based on the similarity of habitat to the nearby Red Hills in south-central Kansas, where the species does famously occur (MacRae 2006b). I’ve been here several times now and never found the species, and that did not change this time either. I did end up finding larval burrows and collecting the larvae of several other tiger beetle species (including the wonderfully ginormous Amblycheila cylindriformis), but again I could only consider this a moderate success. During the day, however, I had noted that eastern red-cedar (Juniperus virginiana) in the area was suffering branch and leader die back. Nearly every tree had at least one or more affected branches, and when I cut into a few of them I found evidence of fresh larval galleries of what I presumed were jewel beetles in the genus Chrysobothris. There are several species in this genus that breed in dead Juniperus, but I’m not familiar with any that attack living plants so pervasively as I was seeing here. Moreover, only a few of these species have been recorded from Oklahoma, so I made a mental note to return to the area in the morning and collect examples of dead/dying branches before driving to my Day 3 destination. I’ll put these up in rearing containers when I return home in an attempt to rear our the adult beetles.

Infested red-cedars atop main mesa.

If you’ve never collected wood for rearing beetles before, all I can say is that it is hard and strenuous work. You have to get pretty good at discriminating infested wood in the field, because you don’t want to expend the effort to cut, de-twig, section, bundle, and carry back to the car batches of wood that don’t end up producing beetles. It was a little more effort than I anticipated to get a good sampling of Juniperus branches due to the hardness of the wood and dullness of my hand saw, along with not considering that I would have to hike up to the top of the mesa and then carry the wood all the way back down. Still, there is something enjoyable about this activity for me—perhaps because I’ve done so much in the past and reared so many great species as a result, and I’ll be anxious to see what species I am able to rear from this batch of wood and if they represent any significant new records.

Returning to the car with the wood, I passed by a mesquite tree (Prosopis glandulosa)—a common denizen of the desert southwest but probably near its northeastern limit of distribution here—and noticed bleeding on the main branches. A little bit of slicing with my knife confirmed my suspicion that this was also the work of jewel beetles in the genus Chrysobothris. In the desert southwest, these trees are attacked commonly by one species in particular, C. octocola, and I wondered if this might be the work of that beetle. I also had my suspicions that this species had not yet been recorded from Oklahoma (I later confirmed that it has not), and since I was already hot and sweaty from collecting the Juniperus wood I figured I might as well use my remaining strength to hack out a few limb sections with bleeding and bring them back as well. As I did this, what did I see on one of the branches but the critter itself! I had a decision to make—stop what I was doing and get out the camera to try to take photos (and risk the beetle flying away), or secure the beetle for now, continue with my hack job, and take photos later. I opted for the latter.

Chrysobothris octocola on stressed Prosopis glandulosa | Major Co., Oklahoma

I have to be honest—the beetle found the day’s travels too much to handle, and by the time I was able to take some photographs it was close to dead. As a result, these photos show the beetle in that dreadful flat-on-its-belly pose that I so detest. Still, only the most observant would know the beetle is not alive and well, and a reasonable photo of a dying beetle is better than no photo at all, no matter how live the beetle may be.

This individual represents a new state record for Oklahoma

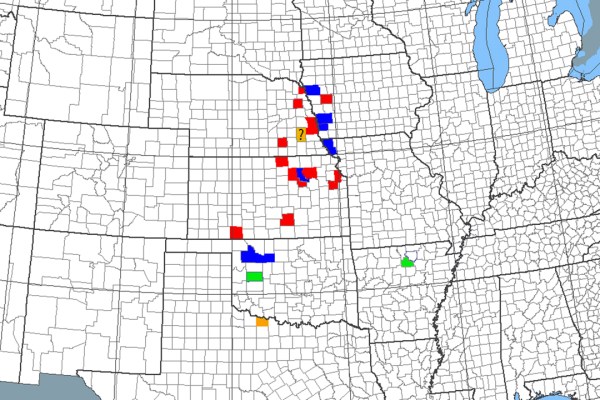

As I mentioned, this species has not been previously recorded as occurring in Oklahoma, so this individual represents a new state record and an expansion of its known distributional range. That’s publishable data, so I’ll be adding the record to a manuscript currently in progress that details new distributional and biological observations for nearly 100 North American species. It’s the latest in a string of such papers that I begun under the tutelage of the late Gayle Nelson (Nelson and MacRae 1990, Nelson et al. 1996) and am now carrying on the tradition (MacRae and Nelson 2003, MacRae 2006b).

A successful morning of wood collecting.

By the time I had finished cutting up and bundling the wood and hauling everything back to the truck, it was already well past noon. My quick little morning stop had consumed nearly half the day. However, with one new state record already under my belt and the possibility of others still hiding within the cedar and mesquite branches that I’d collected, I’d have to say this was already the most successful days of the trip. I couldn’t help notice the irony that, as with Day 1, the most significant find of the day was a jewel beetle on a trip that was supposed to be focused on tiger beetles. Hey, I’ll take success in any taxon on any trip.

REFERENCES:

Nelson, G. H., and T. C. MacRae. 1990. Additional notes on the biology and distribution of Buprestidae (Coleoptera) in North America, III. The Coleopterists Bulletin 44(3):349–354.

Nelson, G. H., R. L. Westcott and T. C. MacRae. 1996. Miscellaneous notes on Buprestidae and Schizopodidae occurring in the United States and Canada, including descriptions of previously unknown sexes of six Agrilus Curtis (Coleoptera). The Coleopterists Bulletin 50(2):183–191.

MacRae, T. C., and G. H. Nelson. 2003. Distributional and biological notes on Buprestidae (Coleoptera) in North and Central America and the West Indies, with validation of one species. The Coleopterists Bulletin 57(1):57–70.

MacRae, T. C. 2006a. Distributional and biological notes on North American Buprestidae (Coleoptera), with comments on variation in Anthaxia (Haplanthaxia) viridicornis (Say) and A. (H.) viridfrons Gory. The Pan-Pacific Entomologist 82(2):166–199.

MacRae, T. C. 2006b. Beetle bits: The “beautiful tiger beetle”. Nature Notes, Journal of the Webster Groves Nature Study Society 78(4):9–12.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2012