Among the 20 or so insects represented in the Green River Formation (GRF) fossils that I currently have on loan, this rather obvious ant (family Formicidae) is the only one that is firmly assignable to the order Hymenoptera (wasps, bees and ants). This is not surprising, as hymenopterans are not well represented among GRF insect fossils. In fact, of the 300+ insect species that have been described from GRF deposits (Wilson 1978), more than two-thirds belong to just three orders—Diptera (flies), Coleoptera (beetles) and Hemiptera (true bugs). Hymenoptera, on the other hand, comprise only 4% of GRF fossils (Dlussky & Rasnitsyn 2002). I presume these numbers are more a result of taphonomic (fossil formation) bias than a true reflection of insect diversity in western North America during the Middle Eocene (47–52 mya).

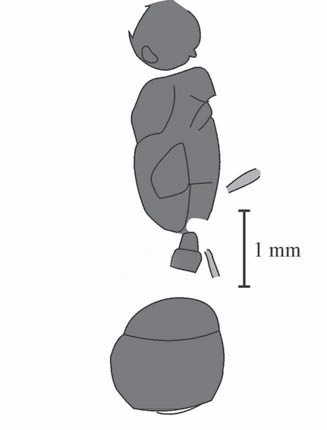

cf. Myrmecites rotundiceps (length = 6.7 mm).

Ants in particular have been poorly represented by GRF deposits. Only four named species were known until Dlussky & Rasnitsyn (2002) reviewed available GRF fossils and increased the number to 18 (15 described as new, one older name placed in synonymy). Diagnoses, line drawings, and keys to all covered subfamilies, genera and species provide one of the best treatments to GRF insect fossils that I’ve come across. According to that work, the fossil in these photos seems comparable to the description and illustration given for Myrmecites rotundiceps, a unique fossil with the general appearance of ants in the subfamily Myrmicinae but differing from all known Eocene and New World fossil ants by its very short, two-segmented waist. The only difference I noted was size—6.7 mm length for my fossil versus 5.5 mm for the holotype (see figure below). Of course, I’m more comfortable identifying extant Coleoptera than extinct Formicidae, so I contacted senior author Gennady M. Dlussky to see if he agreed with my opinion. He graciously sent the following reply:

I agree that specimen on your photo is very similar to Myrmecites rotundiceps. It is larger (holotype is 5.5 mm long), but it may be normal variability. I cannot see another differences.

Myrmecites rotundiceps Gennady & Rasnitsyn 2002, holotype (reproduced from Gennady & Rasnitysyn 2002)

If correctly assigned, M. rotundiceps is the second oldest known member of the subfamily Myrmicinae—the oldest being Eocenidris crassa from Middle Eocene Arkansas amber (45 mya). In fact, the only older ant fossil of any kind in North America is Formicium barryi (Carpenter) from Early Eocene deposits in Tennessee (wing only). [Edit: this is actually the only older Paleocene ant fossil—there are some Cretaceous-aged fossils such as Sphecomyrma freyi (thanks James Trager).] Since myrmicine fossils of comparable age are lacking from other parts of the world, this might suggest a North American origin for the subfamily; however, it could also be an artifact of incomplete knowledge of ants from older deposits in other parts of the world. Myrmicine ants make their first Eurasian appearance in Late Eocene Baltic amber deposits (40 mya) and become more numerous in North America during the early Oligocene (Florissant shales of Colorado, 33 mya). (Dlussky & Rasnitsyn (2002) consider the Middle–Late Eocene ant fauna to represent the beginnings of the modern ant fauna, with extant genera becoming numerous and extinct genera waning but still differing by the preponderance of species in the subfamily Dolichoderinae over Formicinae and Myrmicinae.

USA: Colorado, Rio Blanco Co., Parachute Creek Member.

The photo above shows the entire fossil-bearing rock (also bearing the putative orthopteran posted earlier).

My thanks to Gennady Dlussky and James Trager for offering their opinions on the possible identity of this fossil.

REFERENCES:

Dlussky, G. M. & A. P. Rasnitsyn. 2002. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Formation Green River and some other Middle Eocene deposits of North America. Russian Entomological Journal 11(4):411–436.

Wilson, M. V. H. 1978. Paleogene insect faunas of western North America. Quaestiones Entomologicae 14(1):13–34.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2012