Back in October, I discussed a recent review of the cerambycid genus Tragidion, authored by Ian Swift and Ann Ray and published in the online journal Zootaxa. These gorgeous beetles mimic the so-called “tarantula hawks” (a group of large, predatory wasps in the family Pompilidae) and have been difficult to identify due to poorly-defined species limits, wide range of geographic variation, unusually high sexual dimorphism, and apparent potential for hybridization in areas of geographic overlap. Swift and Ray (2008) recognized seven North American and four Mexican species, including two newly described species and another raised from synonymy. It was an excellent work that provided much needed clarity based on examination of types and included detailed descriptions and dorsal habitus photographs of all species and separate keys to males and females to facilitate their identification. Unfortunately, my summary caused some confusion regarding species that occur in the deserts of southern Arizona, southern New Mexico and western Texas. In this post, I’ll clarify that confusion and provide details for distinguishing these species.

Formerly, it was thought that two species of Tragidion inhabited this region, with populations exhibiting smooth elytra and breeding in dead stalks of Agave and Yucca (Agavaceae) representing T. armatum and those exhibiting ribbed elytra and breeding in dead branches of a variety of woody plants representing T. annulatum. This concept dates back to the landmark monograph of the Cerambycidae of North America by Linsley (1962). Swift and Ray (2008) noted that Linsley’s concept of T. annulatum was based on an erroneously labeled type specimen, and that true T. annulatum referred to populations in California and Baja California (for which other names – now suppressed – were being used). This left the AZ/NM/TX populations attributed to T. annulatum without a name. The previously suppressed name T. densiventre was found to refer to populations inhabiting lowland habitats and breeding in Prosopis and Acacia (Fabaceae), but those occurring in montane habitats and breeding in Quercus (Fagaceae) represented an as yet undescribed species, for which the name T. deceptum was given. I included Swift and Ray’s figure of T. deceptum in my post – but mistakenly included the male of T. densiventre alongside the female of T. deceptum!

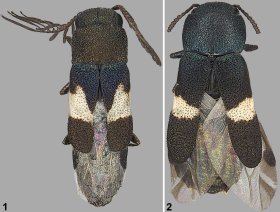

This error may never had been noticed, had it not been for the discriminating eyes of BugGuide contributor, Margarethe Brummermann. Margarethe is currently collecting photographs for a field guide to Arizona beetles and had photographed a male and female of a “ribbed” species in Montosa Canyon. Using the illustration of T. “deceptum” in my post, Margarethe concluded her specimens represented T. deceptum and asked me to confirm her ID. When I told her the specimens represented T. densiventre, her confusion was understandable (given that her male appeared identical to the T. “deceptum” male in my post). Further query on her part prompted me to do a little digging, and I discovered my error. The figure in my post has since been corrected – both that figure and a figure from Swift and Ray (2008) showing the male and female of T. densiventre are included below, along with additional information to allow their identification.

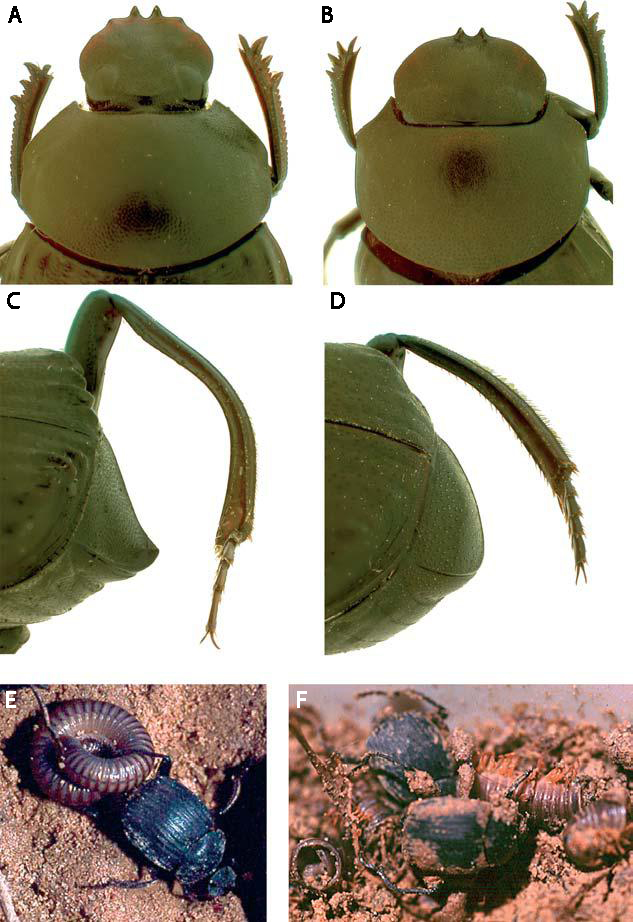

Tragidion densiventre was formerly synonymized under T. auripenne (a rare species known from the four corners region of northern Arizona, southern Utah, southwestern Colorado, and northwestern New Mexico). Males of T. densiventre can be distinguished by their longer antennae, tawny-tan elytra and distinctly red-brown head, legs, and scape, while females have shorter antennae and the elytra red-orange. Both males and females of this species are distinguished from T. deceptum by their five elytral costae that curve inward toward the suture and extend to near the elytral apices, as well as their relatively narrower basal black band. Females of this species may be further distinguished from T. deceptum by their all black (or nearly so) antennae. Tragidion densiventre is found predominantly in xeric lowland desert habitats in Arizona, New Mexico, and west Texas (as well as northern Mexico). Larvae have been recorded developing in dead Prosopis glandulosa and Acacia greggii, and adults have been observed aggregating on sap oozing from stems of Baccharis sarothroides (Asteraceae) and flowers of larval host plants. Although the biology of this species has not been described in detail, it is likely that the observations of Cope (1984) for T. auripenne refer to this species. This is the classic T. “annulatum” commonly observed in the desert southwest.

Tragidion deceptum superficially resembles T. densiventre due to its ribbed elytra; however, it is actually more closely related to the Mexican species T. carinatum. Like T. densiventre, the males exhibit longer antennae and tawny-tan elytra, while females have shorter antennae and orange-red elytra. However, the head, legs and scape of males are black, as in females of the species, rather than red-brown as in males of T. densiventre. Females exhibit distinctly annulated antennae, in contrast to the all black antennae of T. densiventre. Both males and females are distinguished from T. densiventre by the elytral costae – only four rather than five, not incurved towards the suture and extending only to the apical one-third of the elytra. In addition, the basal black band is very broad – exceeding the scutellum by 2 × its length. This species is similarly distributed across the desert southwest as T. densiventre but occurs in more montane habitats, where it breeds in recently dead branches of several species of Quercus. Like T. densiventre, adults are often found feeding and aggregating on Baccharis sarothroides, and in a few lower canyons bordering desert habitats in the Huachuca Mountains of southeastern Arizona this species and T. densiventre have been collected feeding alongside each other on the same Baccharis plants. Tragidion deceptum is one of several species in the genus (along with T. coquus in eastern North America) that have been collected using fermenting molasses traps (more on this in a future post).

REFERENCES:

Cope, J. 1986. Notes on the ecology of western Cerambycidae. The Coleopterists Bulletin, 38:27–36.

Linsley, E. G. 1962. The Cerambycidae of North America. Part III. Taxonomy and classification of the subfamily Cerambycinae, tribes Opsimini through Megaderini. University of California Publicatons in Entomology, 20:1-188, 56 figs.

Swift, I. and A. M. Ray. 2008. A review of the genus Tragidion Audinet-Serville, 1834 (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae: Cerambycinae: Trachyderini). Zootaxa, 1892:1-25.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2009