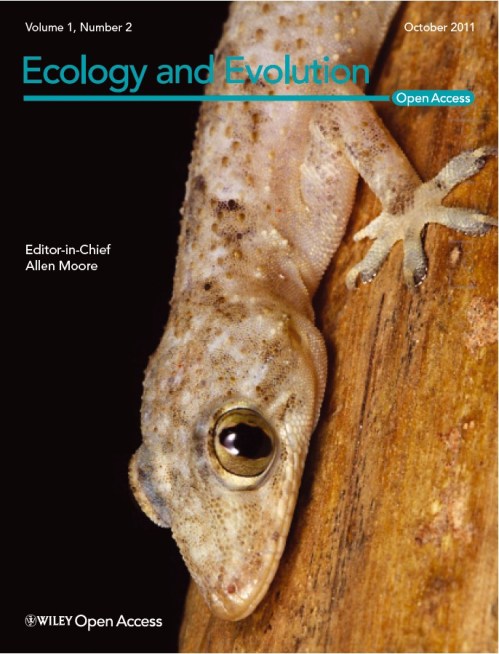

Turkey tails (Trametes versicolor) on lichen-encrusted trunk of fallen post oak (Quercus stellata)—ventral view.

For my friend Rich and I, Thanksgiving week marks the official beginning of the winter hiking season. Fifteen years ago we began our quest to hike the entirety of the Ozark Trail, and with only ~50 of the 350 miles constructed to this point in Missouri to go we find ourselves tantalizingly close to reaching that goal. This year we started the season with 10+ miles of the northernmost Courtois Section. The rains of the previous few days had stopped, but the moisture-laden air still hung heavy under gray, overcast skies. Such a day may not be considered optimal for photography, but nothing could be further from the truth. Lichens and fungi, normally muted and inconspicuous, spring to life when awash with moisture and splash the woodlands with a riot of colors rarely seen on dry, sunny days. The dark, almost black, color of the wet bark adds to the contrast and further emphasizes the ubiquity of these “lower forms of life” amongst the now leafless trees.

Among the most distinctive of these is turkey tail (Trametes versicolor), an extraordinarily common polypore fungus that grows on the trunks of declining and dead deciduous trees—especially oaks. Like all polypore fungi, turkey tail feeds saprophytically within dead and dying wood but is more familiar to us by way of its externally produced reproductive structures, or “tails,” for the release of spores. As the specific epithet suggests, turkey tail comes in a variety of colors ranging from gray through browns to black, and the association of older tails with algal growth even adds greens to the mix. The diversity of colors is found not only within a single locality, but even on a single tree! The especially colorful example shown in these photos, made even more so by its intermixture with green crustose lichens, was found on the trunk of a post oak (Quercus stellata) tree that had fallen across the trail, and I couldn’t help but marvel at the range of colors present and the contrast between the dorsal and ventral surfaces.

Update 30 Dec 2011: Kathie Hodge has provided the following correction to my identification:

Hate to tell you, but the turkey tails in your post aren’t turkey tails, alas, they’re Trichaptum biforme. It’s one of a bunch of shelf fungi that resemble true turkey tails. You can tell them apart by the small, regular pores of Trametes, whereas Trichaptum has a rugged toothy thing going on. Also, T. biforme is paler on top, not as strongly zonate, and has a distinctly purple growing edge (and sometimes the hymenium is delightfully purple too).

Thank you, Kathie, for keeping me on the straight and narrow (and maybe I should stick with beetles in these quizzes!).

Natural light (ISO1600, f/5.6, 1/60 sec)

Full flash (ISO160, f/16, 1/200 sec)

Of course, color is a matter of perception, and I wondered what effect lighting would have on this. When it comes to macrophotography I’m an unapologetic flash-man, preferring the flexibility and sharpness of detail that flash lighting offers over the dreamier “natural” images produced with strictly ambient light. The above comparison, looking at the dorsal surface of the tails with their characteristic concentric zones of colors, did nothing to change that opinion. While some might insist that the natural light photo is a truer representation of the actual colors witnessed, to me it looks gray and faded—no doubt a result of illumination by a large gray light source (the cloudy sky). While my eyes might have seen muted shades of gray and brown, my mind saw vivid shades of rust, orange, and green—colors captured more faithfully by the full-flash illuminated photo.

The strikingly zonate upper surfaces present contrasts in texture as well as color

Congratulations to those of you who guessed some kind of polypore fungus in Super Crop Challenge #10, although nobody correctly deduced an ID below the family level. I fear my challenges have gotten too difficult, as this is the second one straight in which nobody arrived at the correct answer. Nevertheless, on points Mr. Phidippus takes top honors with 11, while Roy, Tim and John earned enough points to receive podium mentions. Session 5 overall leader, Marlin, didn’t play this time, so Mr. Phidippus now takes over the top spot—can he hold onto it as the session plays out?

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2011