Acanthochalcis nigricans | Gloss Mountains State Park, Major Co., Oklahoma

As a student of jewel beetles with an interest in their larval host plant associations, rearing has been an important tool for my studies. Through the years, I’ve retrieved literally hundreds of batches of dead wood from the field and placed them in rearing containers that I keep in my garage. It’s hard work, but the several thousand jewel beetles that I’ve reared from these batches, many representing new distributions, host associations, and even new species (e.g., MacRae 2003) clearly suggest it has been worth the effort. Of course, jewel beetles are not the only insects that emerge from this wood. Numerous other insects have shown up in the rearing containers as well, mostly beetles in other families associated with dead wood such as longhorned beetles, powderpost beetles, checkered beetles, etc. Non-beetles have been reared as well, mostly representing parasitic hymenopterans, and in this group my favorite are the chalcidid wasps (family Chalcididae). Chalcidids and some of their close relatives are instantly recognizable by their greatly swollen and toothed hind femora. Most species in this family are parasitoids of Lepidoptera and Diptera, but some parasitize other insects, including jewel beetles and especially those in the genus Chrysobothris. I have reared a few hundred of these wasps over the years, representing at least a dozen or more species and currently being identified by fellow buprestophile Henry Hespenheide. Once identified, it will be an easy matter to associate these specimens with the Chrysobothris beetles that emerged with them from the same batch of wood. From this, we anticipate that any number of new parasitic wasp/beetle host associations will be revealed.

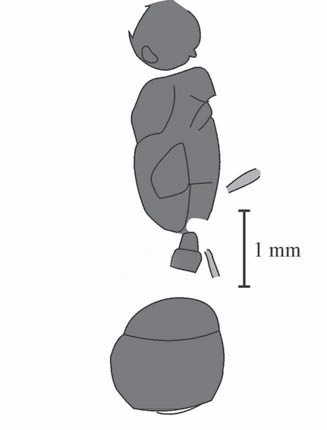

Among chalcidid wasps, the large size and very long ovipositor distinguish this genus.

The chalcidid wasp featured in this post was not reared, but rather was encountered in the field during my recent collecting trip to northwestern Oklahoma. In fact, it was the very first insect that I encountered at the very first site that I stopped at—Gloss Mountains State Park. Although the wasp was photographed on a dead branch of eastern red-cedar (Juniperus virginiana), I first saw it on a dead branch of mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa). Based on its long ovipositor and large size (~19 mm in length, including the ovipositor), I presume this to be one of the two Acanthochalcis species commonly encountered in North America, with the presence of white pubescent patches on its abdomen identifying it as A. nigricans, occurring across the southwestern U.S. from Kansas and Oklahoma to California (A. unispinosa, ranging from Texas to California, lacks these pubescent patches). This species is a known associate of Chrysobothris jewel beetles, including C. femorata and C. edwardsii (Universal Chalcidoidea Database), but in this case I believe it is associated with C. octocola—an equally large jewel beetle that I first encountered on the mesquite at this very spot last fall (a new state record!). I beat quite a few more C. octocola adults from dead mesquite branches during this trip but didn’t find any other Chrysobothris spp. associated with the mesquite. That said, it is possible that the wasp is associated with the larger of two species of Chrysobothris that I beat from the eastern red-cedar at the site (forgive me for being coy about the identity of the beetle right now, as it will be the subject of a future post). However, since all of the wasps I saw that day were originally seen on or flying around dead mesquite branches I’m betting on C. octocola.

The white abdominal pubescent patches distinguish this species from A. unispinosa.

REFERENCE:

MacRae, T. C. 2003. Agrilus (s. str.) betulanigrae MacRae (Coleoptera: Buprestidae: Agrilini), a new species from North America, with comments on subgeneric placement and a key to the otiosus species-group in North America. Zootaxa 380:1–9.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2013