Warning: post contains hardcore, taxonomic, sciencey geekiness!

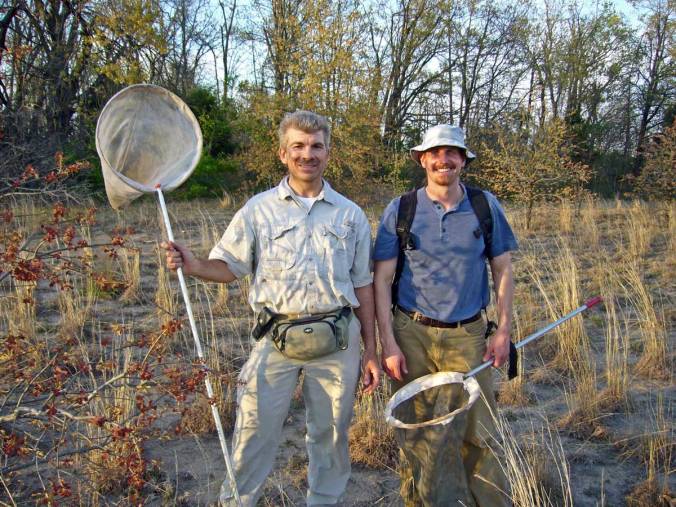

Just as there is seasonality in the lives of insects, there is seasonality in the work of those who study them. For the collector/taxonomist, everything revolves around the collecting season — time spent on anything else is time not available for collecting. As a result, I spend a good deal of my time during the summer in the field and on its associated planning and organizing activities, leaving the winter months for processing and identifying collected specimens, incorporating them into the permanent collection, generating reports to fulfill permit requirements, and ultimately preparing manuscripts for publication — the raison d’être. Winter is also the time when I identify specimens sent to me by other collectors. I do this not only because I’m such a nice guy (at least I hope I am), but also because such material often contains species I haven’t seen before or that represent new distributions and host plant associations that I can use to augment the results of my own studies. Such work has occupied much of my time during the past several weeks, and I now find myself close to finishing the last of the nearly dozen batches of beetles sent to me since the end of last winter.

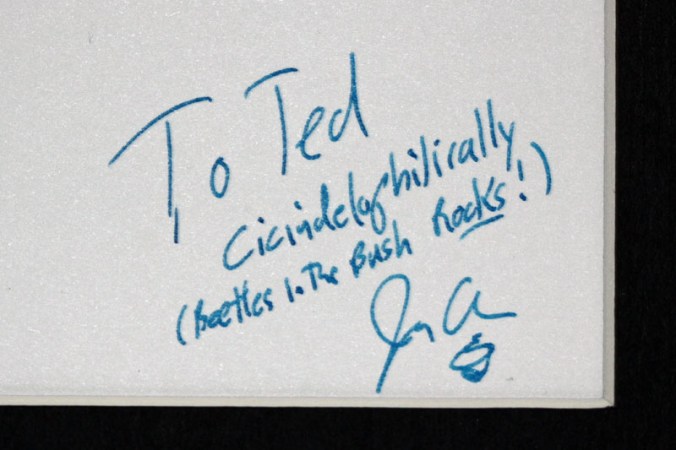

Of the three groups of beetles that I actively study — jewel beetles, longhorned beetles, and tiger beetles — it is the jewel beetles that are taxonomically the most challenging. Tiger beetles can often be indentified in the field (especially with the publication of Pearson et al. (2006), or “the Bible” among cicindelophiles), and North American longhorned beetles have been reasonably well worked by a strong contingent of both professional and amateur taxonomists over the past several decades. Jewel beetles on the other hand, despite their dazzling colors and popularity with collectors, continue to befuddle even the most dedicated collectors due to their extreme variability and poorly-defined species limits. Of the 822 species and subspecies known from North America, fully three-fifths of them belong to one of just three hyperdiverse genera — Acmaeodera, Agrilus, and Chrysobothris. No recent taxonomic treatments are available for any of these genera, thus, identifying species belonging to them requires access to primary literature, a well-represented and authoritatively-identified reference collection, and extraordinary patience! This is particularly true of the genus Acmaeodera, the North American members of which were last treated collectively more than a century ago (Fall 1899) (at which time less than half of the current 149 species/subspecies were known to science). The recent explosion of web-based images has helped matters (a particularly useful site for those interested in North American Acmaeodera is Acmaeoderini Orbis, with its galleries of Harvard type specimens and BugGuide photos); however, images are still lacking for many species, and others are not easily distinguished from the images that do exist.

It is precisely this taxonomic challenge, however, that makes the group so interesting to me. Opportunities for discovery abound, as basic information is incomplete or totally lacking for many species regarding their geographical ranges and life histories. One of the species I encountered in a batch of material sent to me by cerambycid-specialist Jeff Huether contained three specimens that I eventually determined to represent Acmaeodera robigo. Josef Knull (1954) first described this species from specimens collected at Lake Corpus Christi in south Texas, and nothing more was recorded about the species until Nelson et al. (1996) reported a single specimen cut from its pupal cell in the base of Dalea formosa (Fabaceae) at White River Lake in far northern Texas — a range extension of almost 500 miles! Obviously, I didn’t have this species in my collection, and it was only after a series of eliminations that led me to the original description (and confirmation of my ID by Nearctic Acmaeodera-guru Rick Westcott based on the photos shown here) did I know for sure what it was. These specimens were collected at Seminole Canyon State Historic Park, thus, extending into west Texas the species’ known range, and they exhibit variability in the elytral markings and punctation that was not noted in the original description. While only an incremental increase in our knowledge of this species, collectively such increases lead to greater understanding of the genus as a whole, and Jeff’s generosity in allowing me to retain examples of the species increases my U.S. representation of the genus to 130 species/subspecies (87%).

The opportunity for discovery is not limited to range extensions and new host records, but includes new species as well. A few years ago I received a small lot of specimens collected in Arizona by my hymenopterist-friend Mike Arduser (hymenopterists, especially those interested in apoid bees, are excellent “sources” of Acmaeodera, which they encounter frequently on blossoms while collecting bees). Among the material he gave to me was the single specimen shown here that immediately brought to my mind Acmaeodera rubrovittata, recently described from Mexico (Nelson 1994) and for which I had collected part of the type series. Comparison of the specimen with my paratypes, however, showed that it was not that species, and after much combing through the literature I decided that the specimen best fit Acmaeodera robigo (despite being collected in Arizona rather than Texas and not matching the original description exactly). This was before I had true A. robigo with which to compare, so I sent the specimen to Rick Westcott for his opinion. His reply was “good news, bad news” — the specimen did not represent A. robigo, but it didn’t represent any known species either! While the prospect of adding a new species to the U.S. fauna is exciting, basing a description on this single specimen would be ill-advised. Only through study of series of individuals can conclusions be made regarding the extent of the species’ intraspecific variability and its relation to known species. Until such specimens are forthcoming, the specimen will have to sit in my cabinet bearing the label “Acmaeodera n. sp.” For all of you collector-types who live in or plan to visit southeastern Arizona, consider this a general call for potential paratypes! The specimen was collected in early August on flowers of Aloysia sp. near the Atascosa Lookout Trailhead on Ruby Road in Santa Cruz Co.

REFERENCES:

Fall, H. C. 1899. Synonpsis of the species of Acmaeodera of America, north of Mexico. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 7(1):1–37.

[scroll to “Journal of the New York Entomological Society”, “v. 7 1899”, “Seq 12”]

Knull, J. N. 1954. Five new North American species of Buprestidae (Coleoptera). Ohio Journal of Science 54:27–30.

Nelson, G. H. 1994. Six new species of Acmaeodera Eschscholtz from Mexico (Coleoptera: Buprestidae). The Coleopterists Bulletin 48:272–282.

Nelson, G. H., R. L. Westcott and T. C. MacRae. 1996. Miscellaneous notes on Buprestidae and Schizopodidae occurring in the United States and Canada, including descriptions of previously unknown sexes of six Agrilus Curtis (Coleoptera). The Coleopterists Bulletin 50(2):183–191.

Pearson, D. L., C. B. Knisley and C. J. Kazilek. 2006. A Field Guide to the Tiger Beetles of the United States and Canada. Oxford University Press, New York, 227 pp.

Copyright © Ted C. MacRae 2010