When I started participating in blog carnivals last year, Circus of the Spineless was – for me – the pinnacle of blog carnivals. I wanted to take my shot at hosting this venerable celebration of creepy crawlies, and even though the waiting list for hosting was almost a year long, I offered my services and settled in for the long wait until February 2010. Ten months have passed and the time has come. In the meantime, I did my blog carnival host début with Berry Go Round #21 and snatched the sophomore slot for nature blogging’s newest carnival with House of Herps #2. Through those efforts, I learned that blog carnival hosting is an incredible amount of work/fun, and while plants and herps are fascinating, inverts are my true love. It is, thus, with great pride that I join the ranks of previous hosts in presenting this, the 47th edition of CotS. Featured below are 16 submissions by 14 contributors that cover representatives from 5 classes in 3 invertebrate phyla. A humorous look at some of the personalities behind invertebrate study is presented as a bonus for those who make it to the end.

When I started participating in blog carnivals last year, Circus of the Spineless was – for me – the pinnacle of blog carnivals. I wanted to take my shot at hosting this venerable celebration of creepy crawlies, and even though the waiting list for hosting was almost a year long, I offered my services and settled in for the long wait until February 2010. Ten months have passed and the time has come. In the meantime, I did my blog carnival host début with Berry Go Round #21 and snatched the sophomore slot for nature blogging’s newest carnival with House of Herps #2. Through those efforts, I learned that blog carnival hosting is an incredible amount of work/fun, and while plants and herps are fascinating, inverts are my true love. It is, thus, with great pride that I join the ranks of previous hosts in presenting this, the 47th edition of CotS. Featured below are 16 submissions by 14 contributors that cover representatives from 5 classes in 3 invertebrate phyla. A humorous look at some of the personalities behind invertebrate study is presented as a bonus for those who make it to the end.

If you missed last month’s issue, you can find Circus of the Spineless #46 at Kate’s Adventures of a Free Range Urban Primate, and next month’s edition will be hosted by Matt Sarver at The Modern Naturalist.

Phylum CNIDARIA

–Class ANTHOZOA

Coral Reefs

Jeremy at The Voltage Gate reports on peer-reviewed research on the impact of herbivorous fish on the recovery of coral reefs in his post, Protecting herbivorous fishes significantly increases rate of coral recovery. Coral reefs have been hard hit by the challenges of bleaching and disease, pressures likely linked to climate change, and macroalgae, when given the opportunity to dominate, provide even further challenges. This can happen when populations of herbivorous fish, major grazers of macroalgae, are reduced through commercial harvest. The study authors evaluated ten sites over a two-and-a-half year period in and around the Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park (ECLSP), which was established as a no-take marine reserve in 1986, finding an increase of coral cover during the study period from 7 percent to 19 percent. However, ECLSP reefs were responsible for all of this increase, with no net recovery occurring outside the ECLSP. These results illustrate the importance of reserves as a refuge for biodiversity and the service they provide in keeping marine systems intact.

Jeremy at The Voltage Gate reports on peer-reviewed research on the impact of herbivorous fish on the recovery of coral reefs in his post, Protecting herbivorous fishes significantly increases rate of coral recovery. Coral reefs have been hard hit by the challenges of bleaching and disease, pressures likely linked to climate change, and macroalgae, when given the opportunity to dominate, provide even further challenges. This can happen when populations of herbivorous fish, major grazers of macroalgae, are reduced through commercial harvest. The study authors evaluated ten sites over a two-and-a-half year period in and around the Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park (ECLSP), which was established as a no-take marine reserve in 1986, finding an increase of coral cover during the study period from 7 percent to 19 percent. However, ECLSP reefs were responsible for all of this increase, with no net recovery occurring outside the ECLSP. These results illustrate the importance of reserves as a refuge for biodiversity and the service they provide in keeping marine systems intact.

Phylum MOLLUSCA

–Class GASTROPODA¹

—-“Informal Group” OPISTHOBRANCHIA

Sea slug (Glaucus atlanticus)

This gorgeous nudibranch species got a foul slandering when they started washing up on Gold Coast beaches in Australia. Miriam Goldstein debunks this unfair treatment in her post, Sea slugs have self esteem too, at Deep-Sea News, noting its absolutely stunning iridescent blue and silver color with gorgeous feathery tentacles. Further exception is taken with such descriptors as “slimy”, “venomous”, “blue-bottle eating”, and “cannibals” – with the truth behind each of these terms far more fascinating than the visceral reaction their use was intended to elicit. Good news as well – you don’t have to travel to Australia to see these things – they live throughout the world’s open oceans (but you will have to get far from shore, where the pelagic jellys upon which they feed can be found).

This gorgeous nudibranch species got a foul slandering when they started washing up on Gold Coast beaches in Australia. Miriam Goldstein debunks this unfair treatment in her post, Sea slugs have self esteem too, at Deep-Sea News, noting its absolutely stunning iridescent blue and silver color with gorgeous feathery tentacles. Further exception is taken with such descriptors as “slimy”, “venomous”, “blue-bottle eating”, and “cannibals” – with the truth behind each of these terms far more fascinating than the visceral reaction their use was intended to elicit. Good news as well – you don’t have to travel to Australia to see these things – they live throughout the world’s open oceans (but you will have to get far from shore, where the pelagic jellys upon which they feed can be found).

—-“Informal Group” PULMONATA

Iron-clad snail (Cyrsomallon squamiferum)

I’ve known about iron-clad beetles, species of Zopheridae whose exoskeleton is so hard and thick it is almost impossible to impale them with an insect pin. I’d never heard of an iron-clad snail, however, until I read Dr. M’s post, The Evolution of Iron-Clad Samurai Snails With Gold Feet, at Deep-Sea News. Unlike the seemingly iron-impregnated beetles, these snails actually utilize iron sulfide in a series of armor plates covering the “foot.” Just described in 2003 from a hydrothermal vent in the Indian Ocean, it is the only known animal known to use iron sulfide as skeletal material. Only time will tell if these snails achieve the same popularity as living jewelry as the beetles.

I’ve known about iron-clad beetles, species of Zopheridae whose exoskeleton is so hard and thick it is almost impossible to impale them with an insect pin. I’d never heard of an iron-clad snail, however, until I read Dr. M’s post, The Evolution of Iron-Clad Samurai Snails With Gold Feet, at Deep-Sea News. Unlike the seemingly iron-impregnated beetles, these snails actually utilize iron sulfide in a series of armor plates covering the “foot.” Just described in 2003 from a hydrothermal vent in the Indian Ocean, it is the only known animal known to use iron sulfide as skeletal material. Only time will tell if these snails achieve the same popularity as living jewelry as the beetles.

¹ The taxonomy of the Gastropoda is under constant revision, as the results of DNA studies increasingly reveal as possibly polyphyletic many of the former orders (including the Opisthobranchia and Pulmonata, now known as “informal groups”).

Phylum ARTHROPODA

–Class CRUSTACEA

—-Order DECAPODA

Samurai crab (Heikea japonica)

Mike Bok at Arthopoda shares two stories about this crab – one an ancient Japanese legend, the other a modern piece of scientific folklore – in his post, Samurai Crabs: Transmogrified Japanese warriors, the product of artificial selection, or pareidolia? In the first, popular legend alleges that these crabs were transformed from drowned samurai warriors, each one identifiable by the face of the fallen samurai that it bears on its backs and for whom the crab searches in the depths of the oceans around Japan. This ancient legend has led to a modern scientific quibble about whether the stylized face that can be seen on the crab’s carapace is the result of artificial selection by generations of superstitious Japanese fishermen, who have selectively released crabs bearing any resemblance to a human face. This may make for compelling scientific debate, but Mike counters even the considerable eloquence of Carl Sagan in providing his own thoughts on why this likely is not true.

Mike Bok at Arthopoda shares two stories about this crab – one an ancient Japanese legend, the other a modern piece of scientific folklore – in his post, Samurai Crabs: Transmogrified Japanese warriors, the product of artificial selection, or pareidolia? In the first, popular legend alleges that these crabs were transformed from drowned samurai warriors, each one identifiable by the face of the fallen samurai that it bears on its backs and for whom the crab searches in the depths of the oceans around Japan. This ancient legend has led to a modern scientific quibble about whether the stylized face that can be seen on the crab’s carapace is the result of artificial selection by generations of superstitious Japanese fishermen, who have selectively released crabs bearing any resemblance to a human face. This may make for compelling scientific debate, but Mike counters even the considerable eloquence of Carl Sagan in providing his own thoughts on why this likely is not true.

—-Order AMPHIPODA

Amphipod (Phronima spp.)

In another example of the intermixture of science and culture, Mike Bok (Arthopoda) asks, Did Phronima inspire the design of the Alien Queen? Mike agrees with the claim that the original “soldier” alien morph seen in “Alien” (1979) was based on a painting by artist H. R. Giger, but he thinks that Phronima more likely influenced the design of the queen alien morph in “Aliens” (1986). The truth may remain hidden at Stan Winston Studios, but the broad crest atop the head of Phronima, bearing tubular, upward-pointing eyes, its “necro-parasitic” tendencies, and a chillingly suggestive photograph of the beast from a 1981 paper lend an air of plausibility to Mike’s hypothesis.

In another example of the intermixture of science and culture, Mike Bok (Arthopoda) asks, Did Phronima inspire the design of the Alien Queen? Mike agrees with the claim that the original “soldier” alien morph seen in “Alien” (1979) was based on a painting by artist H. R. Giger, but he thinks that Phronima more likely influenced the design of the queen alien morph in “Aliens” (1986). The truth may remain hidden at Stan Winston Studios, but the broad crest atop the head of Phronima, bearing tubular, upward-pointing eyes, its “necro-parasitic” tendencies, and a chillingly suggestive photograph of the beast from a 1981 paper lend an air of plausibility to Mike’s hypothesis.

–Class ARACHNIDA

—-Order PHALANGIDA

Harvestmen, daddy-long-legs

John at Kind of Curious follows up on David Attenborough’s Life in the Undergrowth Episode 1 with his post, Daddy Long Legs Daddies (aka Harvestman). Looking like spiders but lacking their venomous and silk-spinning abilities, it seems that nobody can agree on the proper name for these spider relatives. Brits call them “harvestmen”, but Americans call them “daddy-long-legs”, a term that in the UK refers rather to crane flies (which less informed Americans simply call “giant mosquitoes”). Let’s not even mention the daddy-long-legs spider (Pholcus phalangioides), which actually is a spider.

John at Kind of Curious follows up on David Attenborough’s Life in the Undergrowth Episode 1 with his post, Daddy Long Legs Daddies (aka Harvestman). Looking like spiders but lacking their venomous and silk-spinning abilities, it seems that nobody can agree on the proper name for these spider relatives. Brits call them “harvestmen”, but Americans call them “daddy-long-legs”, a term that in the UK refers rather to crane flies (which less informed Americans simply call “giant mosquitoes”). Let’s not even mention the daddy-long-legs spider (Pholcus phalangioides), which actually is a spider.

—-Order ARANEA

Neoscona crucifera (barn spider)

Anyone who hikes along woodland trails in the eastern U.S. during autumn knows what a “spider stick” is – i.e., any handy stick that can be waved probingly in front of one as they hike, lest they run smack into the web of any number of orb weavers that are fond of stretching their large webs across such natural insect flyways. Jason, at Xenogere, has some biggun’s in his neck of the woods, which he describes in intriguing detail in his post, Walking with spiders – Part 3. Barn spiders are some of the biggest, allowing one to fully appreciate their polychroism and polymorphism. I challenge even the most arachnophic of readers to look at Jason’s photographs and not be mesmerized by their beauty.

Anyone who hikes along woodland trails in the eastern U.S. during autumn knows what a “spider stick” is – i.e., any handy stick that can be waved probingly in front of one as they hike, lest they run smack into the web of any number of orb weavers that are fond of stretching their large webs across such natural insect flyways. Jason, at Xenogere, has some biggun’s in his neck of the woods, which he describes in intriguing detail in his post, Walking with spiders – Part 3. Barn spiders are some of the biggest, allowing one to fully appreciate their polychroism and polymorphism. I challenge even the most arachnophic of readers to look at Jason’s photographs and not be mesmerized by their beauty.

–Class INSECTA

—-Order ODONATA

Autumn meadowhawk dragonfly (Sympetrum vicinum)

Michelle at Rambling Woods~The Road Less Traveled presents a stunning series of photographs of this gorgeous red dragonfly in her post, Circus of The Spineless~Curiosity will conquer fear even more than bravery will.~James Stephens. Perching on her hanging basket of pink-flowered begonias, colors matching perfectly, it was almost as if the dragonfly has staked a claim on the hanging basket as it own personal territory. Where there is one, there are others, and her neighbor’s deck had both a red male and a blue female doing… well, see Michelle’s diagram.

Michelle at Rambling Woods~The Road Less Traveled presents a stunning series of photographs of this gorgeous red dragonfly in her post, Circus of The Spineless~Curiosity will conquer fear even more than bravery will.~James Stephens. Perching on her hanging basket of pink-flowered begonias, colors matching perfectly, it was almost as if the dragonfly has staked a claim on the hanging basket as it own personal territory. Where there is one, there are others, and her neighbor’s deck had both a red male and a blue female doing… well, see Michelle’s diagram.

—-Order COLEOPTERA

Horned passalus (Odontotaenius disjunctus)

Joan Knapp at Anybody Seen My Focus? shows photographs of this beetle in her post, Bess Beetle: Horned Passalus (Odontotaenius disjunctus), as it lumbered slowly and gracefully over a fallen tree branch. Perhaps the cool temperatures were the reason for its sloth. Or perhaps the missing antenna indicated a feeble, old individual on its last (six) legs. A brief interruption for photographs seemed not to deter the beetle from its destination, somewhere in the leaf litter beyond the log…

Joan Knapp at Anybody Seen My Focus? shows photographs of this beetle in her post, Bess Beetle: Horned Passalus (Odontotaenius disjunctus), as it lumbered slowly and gracefully over a fallen tree branch. Perhaps the cool temperatures were the reason for its sloth. Or perhaps the missing antenna indicated a feeble, old individual on its last (six) legs. A brief interruption for photographs seemed not to deter the beetle from its destination, somewhere in the leaf litter beyond the log…

—-Order LEPIDOPTERA

Skipper butterflies (family Hesperiidae)

Randomtruth at Nature of a Man loves skippers (are they butterflies, or aren’t they?), and you’ll love his photographs of these delightful little half-butterflies in his post, Day Skippers. While there is some slight doubt about the identity of individuals he sees in his backyard (skippers are notoriously difficult to identify in the field), there is no doubt that these little guys are loaded with personality. You won’t believe the “natural history” moment he caught on film (er… pixels?) and presented in the final photo sequence.

Randomtruth at Nature of a Man loves skippers (are they butterflies, or aren’t they?), and you’ll love his photographs of these delightful little half-butterflies in his post, Day Skippers. While there is some slight doubt about the identity of individuals he sees in his backyard (skippers are notoriously difficult to identify in the field), there is no doubt that these little guys are loaded with personality. You won’t believe the “natural history” moment he caught on film (er… pixels?) and presented in the final photo sequence.

Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus)

Grrlscientist summarizes a recent peer-reviewed paper in her post, Migratory Monarch Butterflies ‘See’ Earth’s GeoMagnetic Field. The paper reports on photoreceptor proteins in monarch butterflies known as “cryptochromes” that not only allow the butterflies to see ultraviolet light, but also allows them to sense the Earth’s geomagnetic field. These highly conserved proteins evolved from the light-activated bacterial enzyme phytolase, which functions in DNA damage repair. Most animals have one of two types of cryptochromes, but monarchs have both – providing the first genetic evidence that the vertebrate-version of cryptochrome is responsible for the magnetoreception capabilities in migratory birds. Further research may provide insight on the workings of the circadian clock, which could lead to better understanding of sleep disorders and mental illnesses such as depression and seasonal affective disorder, as well as development of new treatments for jet lag and shift-work ailments.

Grrlscientist summarizes a recent peer-reviewed paper in her post, Migratory Monarch Butterflies ‘See’ Earth’s GeoMagnetic Field. The paper reports on photoreceptor proteins in monarch butterflies known as “cryptochromes” that not only allow the butterflies to see ultraviolet light, but also allows them to sense the Earth’s geomagnetic field. These highly conserved proteins evolved from the light-activated bacterial enzyme phytolase, which functions in DNA damage repair. Most animals have one of two types of cryptochromes, but monarchs have both – providing the first genetic evidence that the vertebrate-version of cryptochrome is responsible for the magnetoreception capabilities in migratory birds. Further research may provide insight on the workings of the circadian clock, which could lead to better understanding of sleep disorders and mental illnesses such as depression and seasonal affective disorder, as well as development of new treatments for jet lag and shift-work ailments.

—-Order HYMENOPTERA

Ants (family Formicidae)

Katydids, grasshoppers, cicadas – what do ants have on these singers of the insect world? Plenty, as Roberta at Wild About Ants points out in her post, Ants: No Longer the Strong Silent Types. It turns out that ants have patches of ridge-like structures on their gaster, which they rub against a curved ridge (called a “scraper”) on the petiole to communicate with each other via stridulation. While lacking the decibel level of a cicada, these sounds are nevertheless in the audible range for human ears and are thought to have alarm, mating, and recruitment functions. Even more fascinating, stridulation is not the only tool in the ant music chest – drumming and rattling have also been documented. Curiously, however, ants do not possess ears, rather likely sensing sounds through their legs or by specialized hairs on their antennae. Check out the provided links to SEM photographs and a sound recording.

Katydids, grasshoppers, cicadas – what do ants have on these singers of the insect world? Plenty, as Roberta at Wild About Ants points out in her post, Ants: No Longer the Strong Silent Types. It turns out that ants have patches of ridge-like structures on their gaster, which they rub against a curved ridge (called a “scraper”) on the petiole to communicate with each other via stridulation. While lacking the decibel level of a cicada, these sounds are nevertheless in the audible range for human ears and are thought to have alarm, mating, and recruitment functions. Even more fascinating, stridulation is not the only tool in the ant music chest – drumming and rattling have also been documented. Curiously, however, ants do not possess ears, rather likely sensing sounds through their legs or by specialized hairs on their antennae. Check out the provided links to SEM photographs and a sound recording.

Bald-faced hornet (Dolichovespula maculata)

Diane Tucker, Estate Naturalist at the Hill-Stead Museum in Farmington, Connecticut, writes at Hill-Stead’s Nature Blog. In her post, Be it ever so humble, she takes a look at some of the different animal nests that become revealed during autumn’s leaf drop – particularly those made by the bald-faced hornet (and also birds such as oriole’s). From its start as simple cluster of chambers, to its growth over the course of the summer – growing fatter until the summer’s apex of warmth and light, then tapering off with the approach of fall, these insect homes are a marvel of nature – intricately constructed homes made entirely of paper.

Diane Tucker, Estate Naturalist at the Hill-Stead Museum in Farmington, Connecticut, writes at Hill-Stead’s Nature Blog. In her post, Be it ever so humble, she takes a look at some of the different animal nests that become revealed during autumn’s leaf drop – particularly those made by the bald-faced hornet (and also birds such as oriole’s). From its start as simple cluster of chambers, to its growth over the course of the summer – growing fatter until the summer’s apex of warmth and light, then tapering off with the approach of fall, these insect homes are a marvel of nature – intricately constructed homes made entirely of paper.

—-Order DIPTERA

Common green bottle fly (Lucilia sericata)

Bug Girl discusses the resurging use of bottle fly larvae in her post, Maggot therapy. The academic among us will appreciate her discussion of the mechanisms that allow these seemingly disgusting vermin to function as incredibly delicate microsurge0ns in cleaning and disinfecting open wounds. The morbid among us will appreciate the links to the most entertainingly disgusting medical photos one can imagine. Check it out – but not over your lunch hour!

Bug Girl discusses the resurging use of bottle fly larvae in her post, Maggot therapy. The academic among us will appreciate her discussion of the mechanisms that allow these seemingly disgusting vermin to function as incredibly delicate microsurge0ns in cleaning and disinfecting open wounds. The morbid among us will appreciate the links to the most entertainingly disgusting medical photos one can imagine. Check it out – but not over your lunch hour!

BUGS IN FIR

Wanderin’ Weeta (With Waterfowl and Weeds) was going to make an owl out of Douglas fir cones, but instead she found globular springtails, a crab spider, and a ladybug in a sprig of fir. We’re glad she has an interest in little hitchhikers such as these, even if the kids at school when she was growing up didn’t.

Wanderin’ Weeta (With Waterfowl and Weeds) was going to make an owl out of Douglas fir cones, but instead she found globular springtails, a crab spider, and a ladybug in a sprig of fir. We’re glad she has an interest in little hitchhikers such as these, even if the kids at school when she was growing up didn’t.

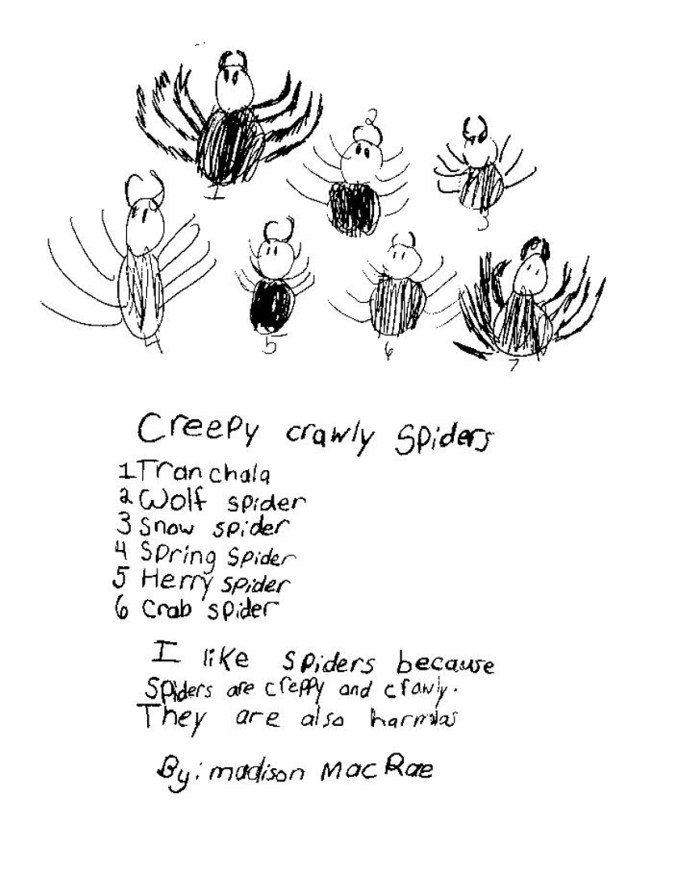

ENTOMOLOGY HUMOR

Bug Girl shows that entomologists have a sense of humor with her post, Monday Morning bug jokes – a video compilation of jokesters from the recent Entomological Society of America Annual Meeting in Indianapolis. My favorites were the best dung beetle pickup line (“Is this stool taken?”) and Marvin Harris’ rendition of the minimum number of insects needed to elicit control (1 pubic louse, or 1/2 codling moth larva :)). J. McPherson was equally, if unwittingly, hilarious due to his Christopher Lloyd-esque mannerisms. My favorite entomological joke of all, however, was not featured, so I offer the following addendum to Bug Girl’s post:

Copyright Ted C. MacRae 2010

Email to a friend

Email to a friend