This—the 18th “Collecting Trip iReport”—covers the second of two insect collecting trips to the southwestern U.S. this season—this first one occurring from June 4–13, during which I placed “bottle traps” and “jug traps” at several locations, and this one from September 3–14 to retrieve the traps and take advantage of any late-season collecting opportunities. I was fortunate on this trip to have longtime collecting buddy and melittologist Mike Arduser joining me, during which we visited the same 15 localities that I visited on my precious trip back in June (one in northwestern Oklahoma, six in northern Arizona, six in southern Utah, and two in southern Nevada) plus two additional localities (one each in northwestern Oklahoma and northeastern New Mexico).

Like previous trip reports, this one assembles field notes largely as they were generated during the trip. They have been lightly “polished” but not substantially rewritten or changed based on subsequent examination of collected specimens (unless expressly indicated by “[Edit…]” in square brackets). While I did photograph a few insects in the field with my “macro” rig to feature individually in future posts, this post contains only iPhone photographs (thus the title “iReport”). Previous collecting trip iReports are:

– 2013 Oklahoma

– 2013 Great Basin

– 2014 Great Plains

– 2015 Texas

– 2018 New Mexico/Texas

– 2018 Arizona

– 2019 Arkansas/Oklahoma

– 2019 Arizona/California

– 2021 West Texas

– 2021 Southwestern U.S.

– 2022 Oklahoma

– 2022 Southwestern U.S.

– 2023 Southwestern U.S.

– 2024 New Mexico: Act 1

– 2024 New Mexico: Act 2

– 2024 New Mexico: Finale

– 2025 Southwestern U.S.: Act 1

Day 1

I’m on my way out west with fellow collector Mike—today being only a travel day but with a quick stop in Texas Co., Oklahoma to retrieve bottle traps set back in June and then a night of camping at Black Mesa State Park before continuing the drive west tomorrow. After 7 hours, we needed to stretch our legs and stopped at Salt Plain National Wildlife Refuge’s Sandpiper Trail—a spot we both have visited several times and know well. Recent rains had the alkaline flats filled with more water than I’ve seen during any previous visit, …

… and only a few Ellipsoptera nevadica knausi (Knaus’ tiger beetle) and Eunota circumpicta johnsoni (Johnson’s tiger beetle) were seen on the drier margins of the alkaline flats. Several Epicauta conferta (red-cornered blister beetle) were seen lumbering across the path, and a Diogmites angustipennis (prairie robber fly) posed nicely on the trail for pictures as well.

Showy Eustoma russellianum (prairie gentian)—a plant I’ve never seen before—were blooming spectacularly and prolifically in the vegetated areas bordering the alkaline flats.

It was a quick but interesting stop that rejuvenated the legs before we continued our journey westward.

The first “real” stop of the trip was ~5 miles north of Goodwell in Texas Co., Oklahoma where I placed three white bottle traps in early June hoping to capture the very rare Acmaeodera robigo, which had been photographed here on flowers of Melampodium leucanthemum (blackfoot daisy) and the photos posted on BugGuide. I was never able to contact the photographer, but since bottle traps are so effective at sampling species of Acmaeodera I reasoned placing three traps here (one at the precise spot and two more several hundred yards to the north and to the south) would give me the best chance of collecting it. It had already been dark for an hour before we reached the spot, but despite the darkness and late hour I had no trouble finding each of three traps. I was happy to see all three traps still in place, undisturbed, and filled to the brim with insects. I tried to pick out the larger insects (mostly crickets and grasshoppers) and stir through the remaining contents of each trap a bit to see if I could detect any Acmaeodera, but the majority of insects appeared to be small blister beetles, followed by bees. The darkness made further sorting impossible, so I bagged the contents of each trap and saved for later sorting. [Edit: later sorting found only a couple of Acmaeodera mixta? in just one of the traps and no A. robigo.]

We arrived at our first overnight spot—Black Mesa State Park—quite late (~11:30 pm) and quickly setup camp before retiring for the evening. In the middle of the night I got up, came out of the tent, and was greeted by an incredible amazing starscape that is normally only seen during winter. Taurus was already high in the sky, and Orion was well above the horizon with a brightly shining Jupiter not too far to its left.

Day 2

In the morning, a canyon towhee (Melozone fusca) kept us company as we prepared breakfast and then broke camp for another mostly travel day

Our destination this evening is Devils Canyon Campground near Monticello, Utah, to which we will travel by way of northeastern New Mexico and then southwestern Colorado.

Shortly after crossing into Colorado we made a pit stop for ice and I began searching the pavement around the gas station looking for beetles that may have come into the previous night’s lights. I didn’t find any cerambycids but I did find a small tenebrionid beetle that didn’t look like familiar to me.

Crossing the Sangre de Cristo and then the San Juan ranges were as spectacular a mountain crossings as any that Colorado has to offer, and a coffee stop in Pagosa Springs (at Faire Society Cafe and Patisserie) provided not only good coffee and pastries to fuel me for the rest of the drive to Devils Canyon Campground near Monticello, Utah, but interesting and creatively framed art work to treat the eyes while waiting for our orders.

Weather during the drive had been good all day, but on the final approach to Devils Canyon Campground the skies began looking worryingly threatening. The last time I came here (early June) I had intended to camp here but got rained out and took a motel in town. I did not want a repeat of that, so we kept our fingers crossed and made the final drive to the campground. Although still threatening, it was not actually raining when we arrived (unlike last time), so we took our chances and set up camp. No sooner than that did the rain start! Fortunately, the tent was already up, so it just meant that instead of cooking dinner at the site, we would instead go to town and have dinner (Dave’s BBQ). When we got back to camp, the rain had stopped (although we could tell that it had rained hard), so I decided to walk the roads looking for night-active beetles. I knew this was probably a fruitless exercise—by then the post-rain temps at this 7000’ site were already down to the mid-50s, but it would give me a chance to stretch my legs after two straight days of driving, and I could also take that opportunity to retrieve the bottle and jug traps that I had set back in June. The bottle trap was disappointing, especially after seeing the ones I’d set near Goodwell, Oklahoma filled to the brim with insects—just a handful of bees (for Mike) and no beetles of any kind. This was surprising given the many Acmaeodera I have collected in alpine habitats just like this (Ponderosa pine and Gambel oak). The SRW-baited jug trap, on the other hand, was nicely (if not overwhelmingly) productive (Tragosoma sp., Enaphalodes sp., small elaphidiines, small acanthocine with very long antennae, Xestoleptura?)—enough to make it worth the effort. I was also pleased to see that the jug trap was in still place and intact with the catch in good shape despite three months in the field. The bait bottle was still about half full of red wine, but since the propylene glycol had dried the trap was no longer trapping insects. As I’d expected, no night-active insects were seen in the way to the traps or on the way back.

Day 3

It was a chilly morning, and though it had not rained since our arrival last night the skies remained overcast. The day’s plan was to continue west to the Ponderosa Grove Campground in southwestern Utah (north of Kanab), but with only five hours of driving required to get there we would have time to make a few stops along the way. Before leaving I started checking the Ericameria nauseosa (rubber rabbitbrush), several of which had begun blooming in the campground, and found a few Crossidius coralinus and Acmaeodera amabilis on the flowers. I was tempted to suggest staying put—at least for a short time—and exploring the area a little more fully, but my real objectives were further west and I elected to stick with the plan.

One of the stops I’d made along this way last June was 4 miles east of Bluff in San Juan Co., Utah, where the famous Mont Cazier had collected what would later be described as Agrilus utahensis. I did not find it in June (nor did I fully expect to, since the record was from late July), and I was equally skeptical about my chances this time given how much later it was in the season. On the way here, we got caught behind an oversized load on the highway that was so big it required three highway patrol chaperone vehicles to clear the road ahead. Going at about half the speed limit, I worried we might have to follow it the entire way to our turnoff, which would nearly double our travel time to the first spot. Fortunately, the caravan pulled over at one point to let the long train of trsffic that had accumulated behind it pass, and we were on our way (the convoy would later pass us at the very spot where we had stopped to collect).

The location was disappointing dry and crispy, although Gutierrezia sarothroides (broom snakeweed) was coming into bloom. Sweeping it eventually produced about a dozen Crossidius pulchellus and two other beetles (a clytrine leaf beetle and a weevil), and Mike collected a handsome series and diversity of bees off of flowering Eriogonum sp. (buckwheat).

Our drive afterwards through southeastern Utah and northeastern Arizona took us through some of the most amazing scenery that the American West has to offer—red sand/siltstones sculpted through the eons by wind and rain have created a landscape that can only be described as “planetary.”

Eventually, the dramatic landscape gave way to a more monotonous series of desert plateaus periodically interrupted by dramatic descents and canyons as we got deeper into north-central Arizona. Though pleasing to the eye, there were few signs of greenery of flowers to tempt the passing entomologist except occasional stands of Ericameria nauseosa (rubber rabbitbrush) beginning to bloom in higher elevation spots. We kept our nose to the grindstone, hoping to see better things once we passed through Page and crossed back into south-central Utah, but the landscape became even crispier, with a stop about 20 miles northwest of Page to look for Nanularia brunnea on Eriogonum inflatum (which I had found two years ago in late June) being a total bust. We expected/hoped that the higher elevations around Ponderosa Grove Campground (~6000’) would provide better collecting and continued there without haste. Our expectations/hopes proved well-founded, as blooming rabbitbrush was seen with greater frequency as we traveled north of Kanab and even more so along Hancock Rd approaching the campground. We took a few moments to scout out a good campsite and setup camp before spending the rest of the available daylight hours exploring. For me the rabbitbrush was most tempting, and scouting plants in the campground and the vicinity east produced small but nice series of Crossidius coralinus and Typocerus balteatus. As I was doing so, a sinking sun and virga to the east produced an impressive rainbow that became irresistible for photography—not only as a subject itself but as a backdrop for the beetles I was finding.

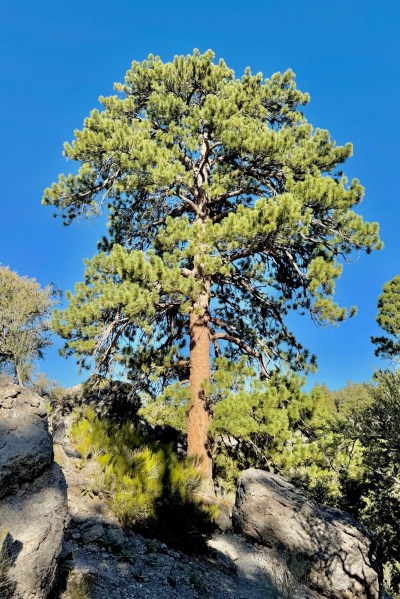

After some downtime back at camp (and grilled sirloin steaks for dinner), I did my customary nighttime patrol to check for night-active insects. This campground was especially productive when I did this back in June and found several Zopherus utahensis and other tenebrionids on the trunks of the massive Ponderosa pines that are the namesake of this campground.

This time was no different—while I found only a single Z. utahensis, I did also find a few specimens of Coelocnemis sulcata, including a mating pair, on the trunks of the trees …

… and a single Embaphion sp. on the ground at the base of another. There are several massively-trunked Juniperus osteosperma (Utah juniper) in the campground as well, on which another C. sulcata was found. Despite this success and the relatively early hour, I was exhausted and called it quits for the night and retire. We will spend the entirety of the day here tomorrow, so I’ll have another chance to check the tree trunks again tomorrow night.

Day 4

After a relaxing morning at the campsite (during which time I caught up on my field notes while enjoying double-pour-through coffee), I walked over to the sand dune-adjacent woodlands to retrieve the traps that I’d set there back in June and brought them back to the campsite for sorting. I was happy to see Ericameria nauseosa (rubber rabbitbrush) and many other plants in bloom and looked forward to checking them more closely after servicing the trap catches.

The yellow bottle trap had ~15-20 beetles, including several Acmaeodera spp., a lepturine cerambycid, and a tiny Dichelonyx-like scarab (a relief after getting skunked with the bottle trap I’d set in Devils Canyon). There were also a fair number of bees in the trap, which I gave to Mike. The SRW-baited jug trap also did well, containing Tragosoma sp., Enaphalodes sp., several Psyrassa sp., and another colorful little lepturine along with several Euphoria inda, several small clerids, a mantispid, and numerous small beetles I take to be oedemerids. After processing the trap catch, I went back over to the woodlands and dunes, spending more than three hours collecting off the flowers of E. nauseosa and other flowers.

Typocerus balteatus was found not uncommonly on the flowers in most of the areas that I covered, while Crossidius coralinus and C. suturalis were found a bit more sparingly.

I also found Acmaeodera rubronotata on the flowers of Grindelia squarrosa (curlycup gumweed), Dieteria canescens (hoary tansyaster), and E. nauseosa, but they were limited to the woodlands and not seen in the dunes.

I also found several individuals of an interesting little weevil on the rabbitbrush flowers, its gray/black longitudinally striped body making a good subject for photography (for which I also brought back a live A. rubronotata and a mating pair of ambush bugs), and spent a bit of time photographing some of the other blooming plants in the area.

By the time I feel like I’d gotten a good enough look at the area, nearly four hours had gone by and I was famished. Sardines and Triscuits did the trick, after which we did a quick ice run into town and back—the highlights being an authentic Sinclair dinosaur (he’s smiling!) and an real (though non-functioning) pay phone.

Returning to the campground, I walked with Mike back into the dunes to retrieve his bowl traps. I had hoped that some of them would pick up Acmaeodera (as is often the case with bowl traps and why I have started utilizing them on my own collecting trips), but the only species that would be out in this area at this time of season would be A. rubronotata, which I had already collected earlier in the day (there were none).

After a period relaxing (with a cold beer and burgers hot off the grill), I began my customary night walk. I have yet to find a cerambycid on tree trunks at night here, but still I enjoy night walks here as much as anywhere due to the consistent presence of ironclad beetles and other tenebrionoids on the trunks of the massive Ponderosa pine trees that give the campground its name.

Tonight would be no different—I found Zopherus uteanus on just the second tree that I examined (right in our campsite), and I would also find two species of tenebrionids in the vicinity on the trunks of ponderosas (Coelocnemis sulcata and Eleodes obscura sulcipennis) and a third species (ID unknown) on the ground at the base of one of them.

At that point, I decided to go outside of the loop towards a couple of large P. ponderosa at the entrance, and on the way I found another E. obscura sulcipennis on the trunk of a massively old Juniperus osteosperma (Utah juniper). There was nothing on the P. ponderosa trees that I had targeted, but nearby was another large one, and high up on the trunk (as far as my fully extended net could reach) was another Z. uteanus, and several C. sulcata—including a mating pair—were found on the ground at its base.

At that point I decided to limit my tenebrionoid collecting to only Zopherus unless I saw species that I hadn’t seen before, so I passed by some additional tenebrionids of the same species as the previous on a large P. ponderosa in the RV loop, then saw a large, multi-branched Pinus edulis (Colorado pinyon pine) that I thought might be interesting to check. I did not find any beetles on it, but I did locate at eye level—with considerable difficulty!—a male Oecanthus californicus (western tree cricket). I was not only able to take a photograph of it with its wings fanned but also record an audio track up close (posted on iNaturalist).

Returning to the tent loop, I checked all of the large P. ponderosa trees and junipers that had—during the past visit and last night—been so productive, but the only beetles I found was a very small tenebrionid that, fortunately, was yet another species I had not previously seen here (ID unknown). After two hours of searching tree trunks, I called an end to the night, which also meant a close to the collecting at this spot—tomorrow we will drive to Kyle Canyon in southern Nevada!

Day 5

Our exit from Ponderosa Grove took us through more of the spectacular canyonland that southern Utah is famous for and past the incredible Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park (so spectacular it is that I think it could—despite its small size—be a national park). A dramatic descent down into the Virgin River valley and the town of Hurricane was only the first such descent—the second one being even more dramatic as I-15 dropped off the edge of the Colorado Plateau along the Virgin River Gorge. The remainder of the drive to Kyle Canyon northwest of Las Vegas was mindnumbing in its contrast—an endless stretch of interstate highway through a vast expanse of low, hot, featureless desert punctuated at regular intervals by palm tree dotted oases, each with a gaudy, glittering casino at its center. Driving up Kyle Canyon Rd put an end to this, however, as each thousand foot gain in elevation brought with it an increasingly interesting landscape. At about 4500’ elevation, I had set a couple of bottle traps—one yellow, one blue—hoping to catch the recently described Acmaeodera raschkoi (whose namesake—Mike Raschko—I had happened to meet at Ponderosa Grove Campground last June a few days before I set the traps!). Mike R. had also placed a bottle trap (white) at the site and was kind enough to reset it for me so I would have three colors sampling the area. Both of my traps were still in place, intact, and filled with numerous Acmaeodera that I take to be A. quadrivittata (along with many bees for Mike A.) and the yellow also containing a larger species that I didn’t immediately recognize (not unusual since I have never collected this area). Unfortunately, I did not see any specimens that appeared to be A. raschkoi, and even more unfortunately the white bottle trap had been pulled from the ground (although I was able to recover a few A. quadrivittata that were still inside the trap). Not much else was going on at the site—only a few things in sparse bloom but no beetles visiting the flowers, nor was there any rabbitbrush around on which to look for Crossidius.

We got a scare when we arrived at the campground and saw a sign at the entrance saying “Campground Full.” This was bad—if this campground was full, then surely the much more heavily used one down below was also full, and I didn’t look forward to spending the rest of the afternoon scrambling for a campsite somewhere in the Spring Mountains. We drove through the campground anyway, and, in fact, there were many campsites available! Looks like somebody forgot to do their job!

Crisis averted, we selected a nice spot overlooking the desert below and set up camp. Cool evening temps come early at this high elevation (~8300’), so with the remaining afternoon hours I retrieved and sorted my SRW-baited jug trap, finding several Tragosoma sp. but, curiously, not a single other longhorned beetle (or any beetle for that matter). Searching around the area afterwards, I extracted a dead Dicerca tenebrosa partial carcass in its emergence hole in a stump of Pinus monophylla (single-leaf pinyon pine), then went back down to the area I had collected last time, focusing especially on the two large half-dead Juniperus osteosperma (Utah juniper) trees on which I had seen damage from the rarely collected Semanotus juniperi (on one of which I collected three adults later that night). There was nothing on the first (the one on which I found the beetles), but at the second one I saw a large wind-thrown branch that I had not noticed last time. It exhibited S. juniperi damage and emergence holes on the lower part, and chopping into it I quickly recovered a dead but intact carcass of yet another S. juniperi adult. Further chopping turned up nothing, and I was about to walk away when I thought maybe I should cut into the upper part of the branch as well to look for evidence smaller woodboring species. Doing so, I quickly encountered a Chrysobothris sp. larva, and with that I decided to bring the entire upper part of the branch back for rearing. There wasn’t much else going on—few plants were in flower and nothing was seen on the trunks of trees or various pieces of downed wood that were laying about, so I went back to camp.

Later in the evening, we watched a spectacular moonrise, then enjoyed “surf ‘n’ turf” (grilled sirloin steak and salmon) before I started up my customary night walk to check tree trunks for night-active beetles.

Last time here when I did this, I found not only S. juniperi but also a few Zopherus uteanus, so I was hopeful for my chance tonight despite the lateness of the season. It started out well—on the first P. monophylla tree that I checked (right at our campsite), I found Oeme costata and a weevil.

Those would be the last live beetles I would see (other than an occasional tenebrionid beetle, none of which I collected). However, I would still find success—back at the J. osteosperma on which I had found three S. juniperi back in June, I found three more. They were not alive, however, but dead carcasses at the base of the tree—two nearly completely intact and the other partially so.

Day 6

We had planned to visit few localities at middle and lower elevations but stopped to check out the profusely-blooming Ericameria nauseosa (rubber rabbitbrush) right outside the campground entrance for bees and beetles. Curiously, hardly anything was seen on the flowers despite the by then late-morning hour, sunny skies, and temps above 70°F. It seemed odd to me that there were no Crossidius beetles on the blooms, and the thought occurred to me that maybe the occurrence of E. nauseosa in the area itself could be a relatively recent phenomenon since it is only seen—albeit profusely—along the roads and highways in the area but nowhere further within the native habitats. With nothing going on, we pushed down to the lowest elevation point that caught our eye on the way in yesterday—the Step Ladder Trailhead at ~6700’.

Again, E. nauseosa was blooming profusely around the parking lot, but a quick perusal made it clear the situation would be similar here as well. Mike, on the other hand, was having good success collecting bees off of E. nauseosa and especially Gutierrezia sarothrae (broom snakeweed), so I was content to stay and refocus by searching for infested wood. I noticed a lot of Quercus gambelii (Gambel oak) and quickly found one with a dead but still attached, fully-barked branch. I broke the branch off the tree, and there in the broken butt of the branch was a large chrysobothroid larvae! This quickly prompted a decision to collect the infested branch and put it up for rearing. A second larvae was found in a small dead (but still fully-barked) tree nearby, which was added to the bundle. While this was going on, Mike found what seemed to be Agrilus blandus? in his net while sweeping bees from the flowers of G. sarothrae. I recall collecting this species in southern California in flowers of Eriogonum (wild buckwheat), so finding it on other flowers—particularly if Eriogonum is in the area (but not seen because it was not blooming) did not seem out of the question. My much more thorough sweeping of the plants around the area where he found it, however, produced no additional specimens. I was also interrupted in my sweeping attempts by a couple of curious bystanders—one a woman from Ukraine who wondered what the plant was that I was sweeping (I told her “broom snakeweed”) and what it was good for (“brooms” I wryly replied and then quickly clarified its role in the ecosystem), and then offered me a beetle collecting tip by telling me about large beetles they call “bombers” and that bite people sitting in spas in Southern California (I presume these are diving beetles in the family Dytiscidae); and the other a young man who was pleased to hear I was from St. Louis because he used to live there when he was married to his ex-wife. This all happened while I was in the middle of my sweeps, so I held the net bag firmly to keep insects from escaping my net until I could resume my sweeping. Eventually, I gave up the ghost and resumed my search for dead, infested wood, eventually finding a Cercocarpus ledifolius (curl-leaf mountain mahogany) tree with one recently-dead and one older dead branch, the former buprestid-infested (verified by cutting into the wood and finding young buprestid larvae) and which I collected for rearing.

After lunch back at the campground and some time spent processing specimens (as well as enjoying the antics of our resident golden-mantled ground squirrel [Callospermophilus lateralis certus]), …

… I wanted to check out the nearby Deer Creek Picnic Area where I’d seen a lot of iNaturalist observations (suggesting it might be an interesting place). At first all I saw was the massive parking lot below an equally massive road-cut slope—the only thing that looked like a trail was a steep drop down to the creek below. I checked it out, only to find it dead-ending at the creek and clambered back up.

Then I saw a gravel trail behind the guardrail on the opposite side of the highway and found it leading to a paved path up the creek. Much of the trail was covered with a deep layer of gravel from flooding (and indeed some of the picnic tables were also nearly completely buried). I hiked the trail as it ascended alongside the creek under massive ponderosa pines until it dead-ended at a gravel road and turned around. The only plants in flower was Ericameria nauseosa (rubber rabbitbrush), and it was only near the highway, and while I saw no insects that I wished to collect, I did see a large Adejeania vexatrix (orange bristle fly) that frustrated my attempts to photograph it until I finally “pre-set” the focus, exposure, and zoom and quickly fired off a few shots at the distance I’d set it for as soon as the fly landed. The virtual lack of insect activity here confirmed what we’ve been seeing in the area as a whole, so I’ll be anxious to leave tomorrow and head for (hopefully) greener pastures at Leeds Canyon back in southwest Utah.

Day 7

The drive from Kyle Canyon to Leeds Canyon was essentially a straight shot on I-15—normally a recipe for extreme boredom; however, coming back up through the Virgin River Gorge was a different, even more awe inspiring experience than the descent two days earlier. Ascending such a steep narrow canyon has the breathtakingly tall canyon bluffs looming high overhead, dwarfing the traffic, even the largest semi tractor trailers, snaking up below, whereas descending into a seemingly bottomless chasm feels a little more “dangerous.” We arrived at Leeds Canyon relatively early thanks to the “only” 3-hours drive. The area looked very dry, but a variety of blooming plants kept us optimistic as we made our way up the canyon road towards Oak Grove Campground at the top.

Sadly, optimism turned to dismay in an instant when we encountered a “Road Closed” sign about halfway up—a result of the ongoing fire risk that has bplagued the area this season. We checked to see if the campground on the other side of the mountain range was available, only to learn that it was closed due to fire damage. At that point, our decision was made for us—we would need to continue another two hours to the Kaibab Plateau where I had my last sets of traps to retrieve and where we could camp at Jacob Lake. While we were here, however, we took the opportunity to stop at a spot along Leeds Creek and see what we could find.

Several different plants were in bloom, on which I’d hoped to find either Acmaeodera or longhorned beetles, the first that I looked at being Dieteria canescens (hoary tansyaster), but I only saw small dasytines (a few of which I collected). Nothing was seen on Solidago velutinus (velvety goldenrod) or Sphaeralcea grossulariifolia (gooseberry leaf globemallow) flowers, but then Mike came up with a Crossidius discoideus on flowers of Gutierrezia sarothrae (broom snakeweed).

Careful searching of the plants in the surrounding area atop a small hill turned up an additional half-dozen individuals, but none were seen on any of the plants further up or down along the road. By this time, we’d spent about an hour and decided to finish the additional 2-hours drive needed to get to Jacob Lake.

Some of the western U.S.’s worst fires this season occurred on Arizona’s Kaibab Plateau. The Dragon Bravo Fire destroyed over 100 structures on the Grand Canyon’s North Rim—including the historic Grand Canyon Lodge and the North Rim Visitor Center, while the White Sage Fire simultaneously burned significant areas of Kaibab National Forest north and east of Jacob Lake. It was the latter that, unfortunately, swept across both of the sites where I had placed traps a month earlier in June, so I was not optimistic about the likelihood that they had survived. Fortunately, the fires did not reach the immediate vicinity of Jacob Lake, so the campground was unaffected and—unusual in my experience—nearly devoid of people. After setting up camp, I went back north into the burn zone to see if my traps 1) had survived and 2) could be retrieved. The area around the site was almost completely destroyed, with charred black skeletons of trees dotting blackened soils devoid of any vegetation.

I had low expectations for the traps at this site even before the fires, as the area had already burned several years early and was in the early stages of recovery (I had decided to place traps here anyway because I wanted to see what the woodboring beetle fauna in a recovering area might look like).

I continued walking the 2-track toward the trap location surveying the damage, came around a bend, and saw it—a lone, still-green pinyon pine with my jug trap hanging from a branch and a bottle trap, its yellow funnel only slightly heat deformed, still planted in the soil beneath the tree!

At first I was elated, but then I saw the jug trap reservoir was dry and almost completely empty save for a few dried beetle carcasses—the trap had survived the fires, but the associated winds had blown the trap and dumped the contents (none of which could be detected on the ground beneath). The bottle trap, on the other had, looked to be full of insects with plenty of liquid still in the reservoir, so I was hopeful that I would retrieve some good specimens from it. This proved to be the case (sort of!) as I pulled a few Anthaxia sp., a meloid, and lots of bees (for Mike) from the trap. The dried carcasses in the SRW-baited jug trap turned out to be an elaphidiine & several silphids.

After leaving the first trap site and driving towards the second (a few miles east of Jacob Lake), I saw little to no fire impacts as I continued east of Jacob Lake. However, as I got closer to the site I began to see impacts—first along the ridge above, then down the slope and engulfing the area where I had placed my traps. Fortunately, the fire did not seem to have been as severe in the immediate area, so I remained hopeful.

The bottle trap was found first and was in much the same condition as the bottle trap at the previous location—it’s blue funnel slightly heat-deformed, but the reservoir was filled with liquid and insects. Later sorting yielded an Acmaeodera diffusa?, a Melanophila sp., a couple of Anthaxia sp., a clerid, and lots of bees (for Mike). The Melanophila sp. was especially welcome—known collectively as “fire beetles” for their attraction to active fires, its presence in the trap may have been been a direct result of the fire. The SRW-baited jug trap was quickly found next, and much to my relief the trap was not only intact and undamaged but also filled with insects (in fact, the propylene glycol had not even completely dried). Later sorting would yield only a single longhorned beetle (plus a silphid and a Euphoria inda), but that longhorned beetle would prove to be the catch of the trip—Calloides nobilis mormonus! I have reared a single individual of the nominate subspecies from fire-damaged oak collected in Missouri, so I suspect the presence of this beetle is also a direct result of the fires that swept through the area—a satisfying irony.

Back at camp and after another “surf & turf” dinner of sirloin steak and salmon, I did my customary nighttime walk to look for night-active beetles on the ground and in tree trunks. I had good luck with this here back in June, finding a Zopherus uteanus and several other beetles, but tonight’s catch consisted of just a single Temnochila sp. (family Trogosittidae) and a single weevil (superfamily Curculionoidea) crawling on the large trunks of Pinus ponderosa.

Day 8

I’d seen a fair amount of Ericameria nauseosa (rubber rabbitbrush) in bloom at the second site the previous day when I retrieved my traps but didn’t see any insects (or, at least, beetles or bees) on them. I figured this was due to the early evening hour, so we decided to come back during the day to try again. The E. nauseosa flowers were still, puzzlingly, devoid of insects (save for honey bees and enormous numbers of a large, black, bristly tachinine fly—possibly Archytas metallicus or Juriniopsis adusta).

Like at Kyle Canyon, the absence of Crossidius spp. on E. nauseosa flowers was surprising, as I have seen them on this plant at almost every other location I have ever checked. You can’t make things appear no matter how hard you look, however, so we continued into some openings farther up the slop and encountered a few other plants in bloom. One was Dieteria canescens (hoary tansyaster), on the flowers of which I found a few small beetles of an unknown family. Nearby I saw several dead main branches in a clump of Quercus gambelli (Gambel oak)—cutting into them revealed a very small woodboring beetle larvae, so I collected several of the stems for rearing. Coming back down the slope I found a single cryptocephaline on the flower of Eriogonum racemosa (redroot buckwheat) and a single Acmaeidera rubronotata on flowers of Gutierrezia sarothrae (broom snakeweed)—the latter on which Mike had also found a single Crossidius discoideus. (This seems to be the first record of any species of Crossidius from the Kaibab Plateau! Maybe the other species are here as well but are not quite out yet at this relatively early date in fall.)

We were getting ready to leave when I spotted a large, fallen Pinus ponderosa (Ponderosa pine) with the twigs brown but still attached (indicating it might be the right “amount” of dead to host woodboring beetles. Damage by such could be seen on the smaller branches, and cutting into them confirmed the presence of larvae and led to a second wood-cutting/bundling session to bring the beetle-infested twigs and branches back for rearing.

Chasing more floriferous pastures, we went back up to higher elevations and stopped at a spot close to the campground where we 1) saw a great diversity of plants in bloom and 2) could safely pull off the highway. A huge diversity of blooming plants were seen (from which Mike collected ~20 species of bees), but the only beetles of interest that I saw and collected were numerous small black/red cryptocephalines on the flowers of Eriogonum racemosum (redroot buckwheat). After Mike was satisfied he’d sufficiently sampled the diversity of bees at the site, we looked for another place to collect.

We drove south towards DeMotte Campground on Hwy 67, but much of the landscape was complete devastation due to the fires and no access was allowed beyond Kaibab Lodge. It was depressing to see the immense scale of destruction and loss of natural resources, but as one forest worker that Mike talked to put it, “It’s just trees, and he didn’t have to call anybody’s family [i.e., there was no loss of life].” We then drove back down past my second trap location where we had collected earlier in the day to see if we could find better stands of Gutierrezia sarothrae (broom snakeweed) on which to look for more Crossidius discoideus (still represented in the area by the single individual Mike had collected earlier). We drove through even more complete and utter destruction but eventually found undamaged areas at about 6600’ elevation. Not only was there G. sarothrae in bloom, but also Chrysothamnus visicidiorus (green rabbitbrush) and Ericameria nauseosa (rubber rabbitbrush)—all three species serving as hosts for various Crossidius and providing a perfect scenario for comparing and contrasting the sometimes-tricky-to-identify plants! The promise of Crossidius, however, would not be realized, and after an hour of searching—finding only a lone weevil on the flowers of E. nauseosa—did I finally admit defeat and concede that Crossidius from this after would have to come some other time.

I hadn’t planned to do my customary nighttime walk this evening—my motivation waning after the less than meager success of the previous night, continuing relative absence of beetle life I’d seen during the day, and temps now dropping towards the 50s. A cute but shy Uinta chipmunk in our campsite captured my photographic interest as we relaxed, and the setting sun turned the clouds a stunning pink!

However, as night fell the siren song of the nighttime walk began singing its tune and I was unable to resist.

It turned out to be a more successful night than I’d expected—I found a small species of tenebrionid [Edit 10/1/25: Eleodes pimelioides] on the rocks surrounding the campsite, and there turned out to be dozens of the little buggers crawling though the pine duff in the campground.

Eleodes pimelioides (family Tenebrionidae) in alpine coniferous forest at night.

Nothing else was seen, however, and since tomorrow would be a long travel day I called it an early night.

Day 9

On a mostly travel day, we tried to take a big bite out of the many miles that still separate us from St. Louis, where we planned to be in three days time. We got another look at the devastation east of Jacob Lake before reaching the dramatic drop off the Kaibab Plateau and down into the Vermilion Cliffs National Monument—their massive red bluffs accompanying us all the way to Mojave Canyon. Just south of there as the highway climbed up and out of the valley, we made a quick stop to remove excess clothing (having gone from high elevation to low), and alongside the road I spotted a Crossidius pulchellus on the flowers of Gutierrezia sarothrae (broom snakeweed). This is the furthest southwest I have collected this species, and I was tempted to continue looking to see if I could find the other G. sarothrae associate—C. discoideus—as well. We still had a long drive ahead of us, however (destination Mills Rim Campground in northeastern New Mexico), so I resisted temptation and we continued the drive.

The Vermilion Cliffs, stunning as they were, still weren’t the highlight of the drive. That honor would come from the moonscape formations along Hwy 89 as it followed the Echo Cliffs and then turned east onto Hwy 160 towards Tuba City. We then passed through a series of stunning plateaus and drops on Hwy 264 as it passed through the Navajo and Hopi Reservations. One abandoned house as we dropped down off the Ganado Mesa was especially picture-worthy.

Eventually we crossed the state line at Picture Rocks into New Mexico, and, suddenly, the landscape seemed more “tame” and less hostile. I don’t normally like interstates, and the stretch of I-40 to Albuquerque did nothing to change my opinion of them, but I must admit that I-25 north towards Santa Fe was among the most picturesque I have ever seen. Eventually, we left the mountains and found ourselves once again on the western edge of the Great Plains—its vast featureless expanse a true contrast to the landscape we had witnessed throughout most of the day. This apparent homogeneity, however, is misleading—tucked away in places unknown to most are some remarkable natural areas, and Mills Rim is one such place. We arrived after dark, so the explorations of its hidden charms would have to wait until the next day, but after getting camp set up I did a short nighttime walk to see what was out and about.

Only one beetle, Stenomorpha sp. (family Tenebrionidae) ambling across the ground, was seen.

Many plants in bloom were also seen however, so I went to bed optimistic about my prospects for finding beetles the next day.

Day 10

Mosquitoes were bad during the previous night, and they were bad again the following morning, prompting liberal use of repellent to a much greater degree than I am used to. At the same time, the presence of mosquitoes indicates abundant moisture in an area, and it was with that optimism that I set about searching for jewel beetles, longhorned beetles, tiger beetles, and whatever other insects could catch my eye in this hidden jewel of a place. Surrounded by treeless grasslands (and preserved as the Kiowa National Grasslands), Mills Rim Campground sits at the edge of Mills Canyon—a chasm in the landscape at the edge of a plateau bordering the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Firmly embedded in the Great Plains, the juniper/pine/oak woodland at the edge of and down in the canyon features plants and animals at their easternmost extent—residents of the Rocky Mountains that have found an isolated home in the middle of the grasslands. Pinus edulis (Colorado pinyon pine), Pinus ponderosa (Ponderosa pine), Juniperus monosperma (one-seed juniper), Juniperus scopulorum (Rocky Mountain juniper), Quercus grisea (gray oak), and Quercus × undulata (wavy leaf oak) all make their homes here, hosting innumerable insect species that are normally more at home in the Rocky Mountains.

I’ve collected here several times and recorded many different western species of beetles, but the height of the season seems to be in June and July. Mid-September, in contrast, seems to be near the tail end of the season, the numbers and diversity of beetles and other insects dropping from their highs earlier in the season. The flowers of Gutierrezia sarothrae, however, were hosting lots of insects. In addition to Crossidius pulchellus, Chauliognathus basalis, Bothrotes canalicularis, and Collops sp., Mike found numerous bee species, mostly females, collecting pollen from the flowers.

A couple of species of robber flies—Ospricerus sp. and Efferia sp.—were also taken in flight, presumably patrolling the flowers of G. sarothrae for bee prey.

After a rest and rehydration break, I followed the road down Mills Canyon as it approaches the Canadian River to see if I could find Ericameria nauseosa—should I be able to, it would surely be at or near the easternmost limit of occurrence for the species in this part of New Mexico.

About half a mile down the road I began seeing Acmaeodera rubronotata on the flowers of G. sarothrae, and I eventually secured a series of about a half dozen specimens. This is a nice record, as I found a single specimen a couple of years ago at Black Mesa in northwestern Oklahoma—a new state record and northeastern range extension, and this record helps bridge the gap between that record and the species’ more normal range of distribution across New Mexico and Arizona. Finally, nearly a mile into the canyon, I found one large blooming E. nauseosa and a smaller pre-bloom plant, but there were no Crossidius beetles on them, nor were any additional plants were seen a hundred yards or so further down the road, so I turned around.

On the way back out of the canyon, I collected a Calopteron sp. (family Lycidae) on senescing Melilotus alba (white clover) and photographed a female Stagmomantis limbata (Arizona mantis—family Mantidae).

Back at camp, a couple of scarabaeoid beetles flew to the light of the lamp while we were relaxing with refreshments in hand and waiting for the coals to be ready. This suggested that maybe conditions were favorable for setting up the ultraviolet lights to attract other insects.

After finishing dinner, we did exactly that and saw a few interesting insects show up, but shortly after setting up the lights the wind began to kick up, the temps began to drop, and increasingly frequent gusts making further lighting impossible!

Day 11

It was a rather sleepless final night in the tent—winds whipped as we turned in for the night, and shortly afterwards we awoke to rain splattering our faces through the fly-less tent roof. We quick got up and put on the rain fly, then listened to light but steady rain for most of the rest of the night. By the time we got up it had mostly stopped, but cool conditions with low-hanging, fast-moving clouds caused us to quickly break camp and save coffee and breakfast for Mocks Coffee Shop in Clayton, New Mexico near the Oklahoma state line (let me tell you how difficult it was for me to drive two hours first thing in the morning without coffee!). We had wanted to make our final collecting stop at a a lot near Kenton in the Black Mesa area of extreme northwestern Oklahoma, but the forecast for the area showed only slightly warmer temperatures and very gusty winds. This would make collecting there pointless, so we instead traveled four more hours east to get in front of the cold front at another of our favorite collecting spots, Gloss Mountain State Park in Major Co.

I was hoping to see an attractive late-season jewel beetle—Acmaeodera macra, which I had collected here and at nearby Alabaster Caverns State Park in previous years during late September. Temps were good (well over 80°F) when we arrived but the hour was already late (near 4:00 p.m.), so we had limited time for collecting before insects would start bedding down for the evening (usually around 5:00 to 6:00 p.m. at this point in the season). Megatibicen dorsata (bush cicada) and Neotibicen aurífera (prairie cicada) males were still singing abundantly, filling the air with their distinctive songs (video of M. dorsata male singing here).

Helianthus annuus (annual sunflower) and Grindelia ciliata (wax goldenweed) were blooming prolifically, off the flowers of which Mike collected a fair diversity of bees. I’d hoped to find beetles on the flowers as well, but they were limited almost exclusively to Chauliognathus limbicollis.

I did collect a male/female pair of Tetraopes femoratus (red-femured milkweed borer) on the seed pod of Asclepias engelmanniana (Engelmann’s milkweed) and photographed the striking and beautiful caterpillar of Schinia gaurae (clouded crimson moth) on the stem of Oenethera glaucifolia (false gaura).

After that, I went up on top of the main mesa where I expected A. macra to occur. Heterotheca stenophylla (stiffleaf false goldenaster), on the flowers of which I collected A. macra in previous years, was blooming abundantly, but intense searching their flowers produced no beetles. I also noticed that Gutierrezia sarothrae (broom snakeweed), abundant in the area as well, was in only the earliest stages of bloom, suggesting to me that it might still be a bit too early for the jewel beetles to be out. By the time the 6:00 hour arrived, insect activity was noticeably diminished, and we wrapped up this, our final, collecting stop of the trip.

No camping is available at Gloss Mountain State Park, so we knocked out another hour and a half of travel by driving to Ponca City in north-central Oklahoma and taking a hotel there. For the first time since we left, we enjoyed dinner at a restaurant (fried catfish for me!), a hot shower, and a real bed!

Day 12

The following morning, we were surprised to learn that the only coffee shops in town were Starbuck’s and drive-throughs. This just wasn’t going to cut it for us on our final travel day, so we drove 15 minutes north to the small town of Newkirk and enjoyed great coffee, breakfast sandwiches, and scones at “Savvy Cactus” (Newkirk Mercantile Boutique & Espresso Bar). (The coffee was good enough that I bought a bag of their coffee!)

The rest of the drive back to St. Louis was spent reflecting on the many experiences we’d just had and synthesizing the new knowledge while enjoying the landscape as it skirted the southern edge of the Flint Hills of Kansas and traversed the familiar hills and dales of our beloved Missouri Ozarks—the end of a 3,931-mile trip!

©️ Ted C. MacRae 2025